iFixit revealed a full teardown of Magic Leap One Creator Edition recently along with some long-awaited clarity about how the system operates.

The teardown from iFixit credits Oculus founder (and former Facebook employee) Palmer Luckey with helping tear down the “Lightwear” glasses, which rely on a “Lightpack” processing unit that’s wired and worn on your side. Head on over to iFixit to see all the teardown photos or to Luckey’s website to read his review of the device. He also, by the way, suggests the headset sold fewer than 3,000 units so far.

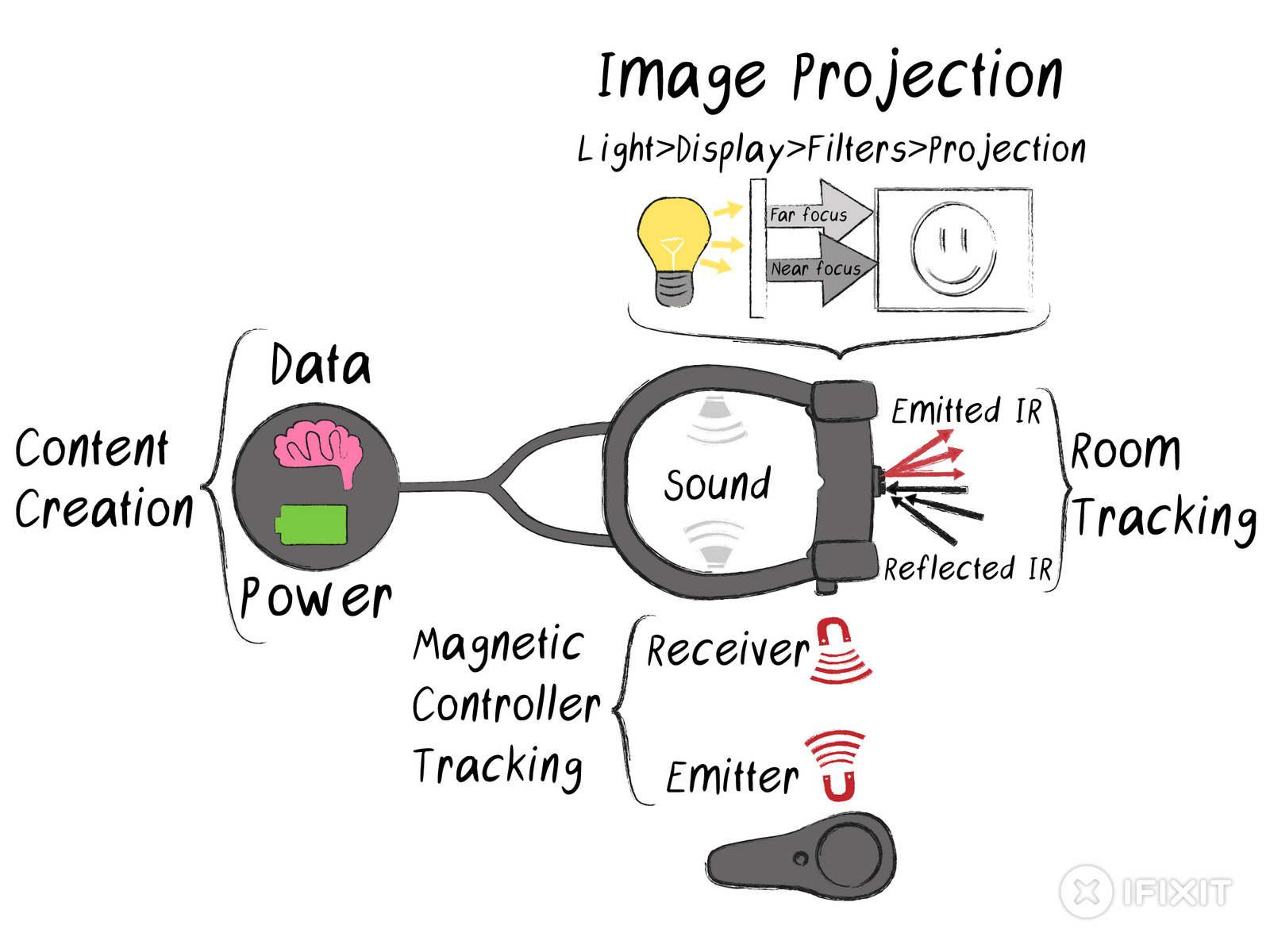

The following illustration from iFixit breaks down the basic way the system functions as content flows from Lightpack to Lightwear:

Diving a little deeper, iFixit explains Magic Leap One uses color-specific waveguides to deliver visuals at two distinct focal planes, each composed of red-green-blue. This makes Magic Leap One a fixed multifocal display.

Not Exactly A Light Field Display

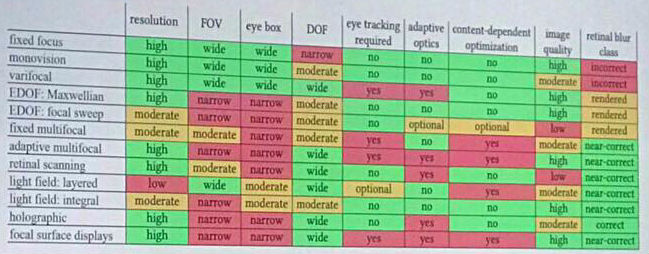

Don’t take it as a definitive guide, but the chart below shows a variety of display types for mixed reality as seen in a presentation by Facebook Reality Labs researcher Douglas Lanman at Display Week earlier this year.

Lanman’s presentation explained Facebook’s steps toward an opaque varifocal headset for VR. That’s quite a bit different from a see-through fixed multifocal headset like Magic Leap is using for AR.

In the chart above, you can see fixed focus headsets at the top. Those are the types of headsets we have today like HoloLens, Rift, Vive, PSVR, Daydream, and Gear VR. Fixed focus headsets usually fix your focus at a distance and render the environment and all digital elements at that distance.

From the chart above, a varifocal headset like Half Dome and a multifocal headset like Magic Leap One have something in common — they both depend on eye tracking to get digital objects to the right focal depth. Magic Leap One apparently decides on which plane to put content by flashing imperceptible lights into the corners of your pupil and measuring changes in the reflections.

Here are those lights as seen through a high-frame rate camera:

Tracking eye movements is not unique to Magic Leap. Apple bought SMI, one of the leaders in this area, and many other companies are exploring the technology with partners like Tobii. StarVR’s new ultra-high end commercial VR headset relies on eye-tracking to enable foveated rendering over an ultra-wide field of view and VRgineers’ enterprise XTAL headset uses eye-tracking to adjust IPD mechanically. If Facebook’s Half Dome ever makes it to market it likely will need eye-tracking too.

Optics And Eye Strain

Will VR and AR headsets be comfortable enough for most people to wear most of the day? The answer to this question may be related to the type of optical design used.

So far, most headsets from HoloLens to Oculus Rift and Vive Pro have been fixed focus headsets which struggle with the vergence-accommodation conflict. When you focus on digital objects that should be closer to you digitally, your eyes naturally want to point inward toward one another. Since the headset is focusing your eyes at a different distance the mismatch can create eyestrain in current headsets. In Stanford researcher Jeremy Bailenson’s book Experience on Demand he noted “most academics and thought leaders in VR believe this problem will prevent long-term use of headsets.”

I asked Bailenson for clarification to see if a fixed multifocal or varifocal headset would make a difference.

“There is a generally shared viewpoint among engineers and perceptual scientists that solving the vergence-accommodation conflict will reduce eye-strain for longer use cases of AR and VR,” Bailenson wrote in an email. ” I have only seen one demo that can linearly shift the focus of a display (as opposed to swap between a handful of focal points). It was incredible from pure ‘amazement’ standpoint. But there is not data that I am aware of that quantifies the degree of improvement there will be regarding simulator sickness, especially in terms of long-term use.”

Here’s how Lanman described the problem to me earlier this year:

“Nearly all consumer HMDs present a single fixed focus. Some have focus knobs, but most just lock the optical focus of the displays to something around two meters. When you look at a near object, vergence (eye rotation) and accommodation (deformation of the eye’s crystalline lens) move together. As your lens deforms to focus on a nearby virtual object, it is focusing away from the fixed focus of the HMD. So, most people report seeing some blur. Sustained vergence-accommodation conflict has been linked, in prior vision science publications, to visual fatigue, including eye strain.”

Magic Leap One appears to be the first standalone AR headset which begins to track eye movements to place digital content at a couple different depths. Is this approach more comfortable for your eyes? The answer isn’t clear yet, but Luckey’s technical breakdown notes getting this right “is even more important for AR than VR, since you have to blend digital elements with real-world elements that are consistently correct.”

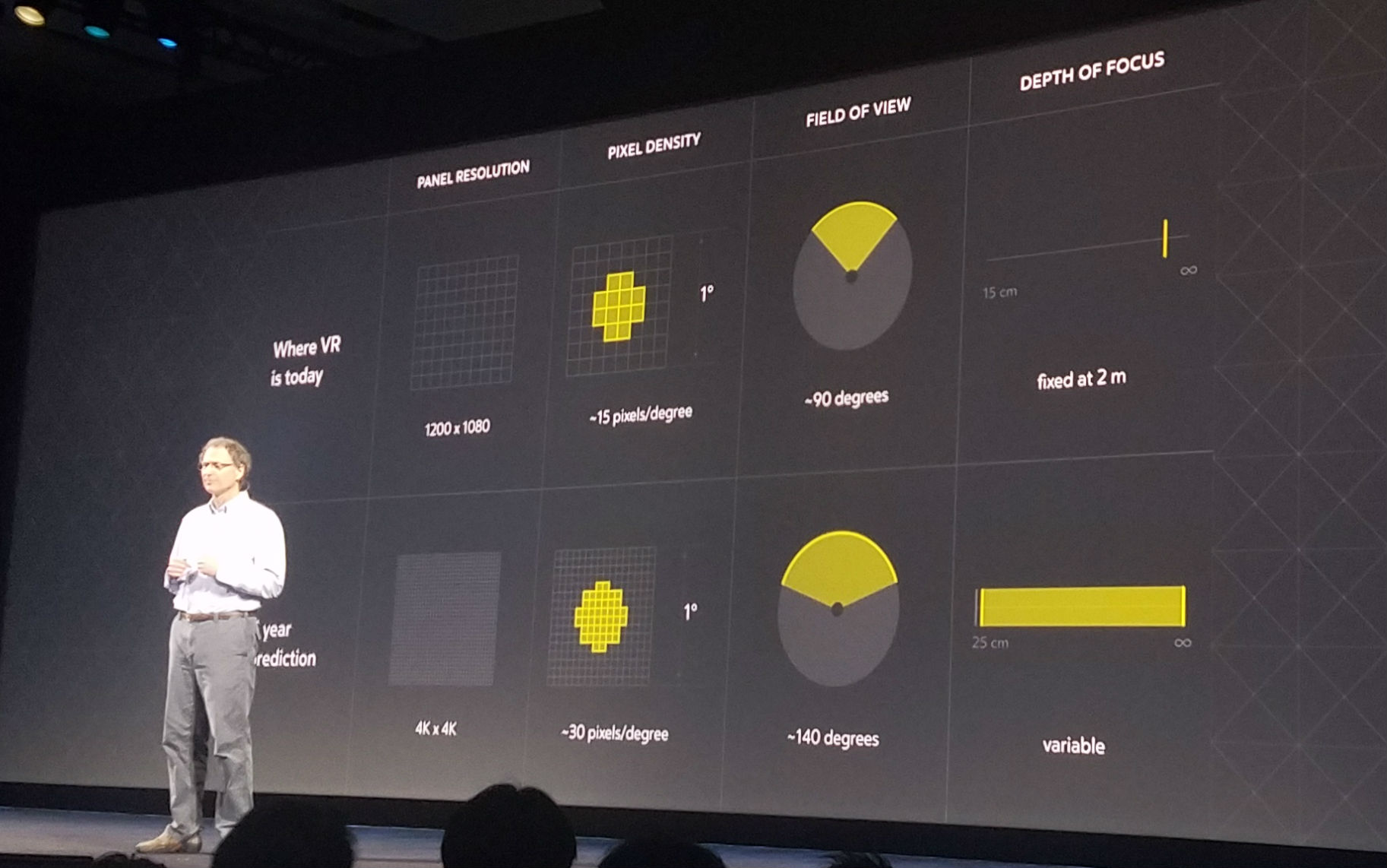

While a modern VR headset already delivers digital content over a far wider field of view than current AR headsets, the varifocal Half Dome architecture Facebook debuted earlier this year would also track eye movements to get the focal distance right all the time, at least theoretically.

Half Dome physically moves elements of the display in tandem with pupil movement:

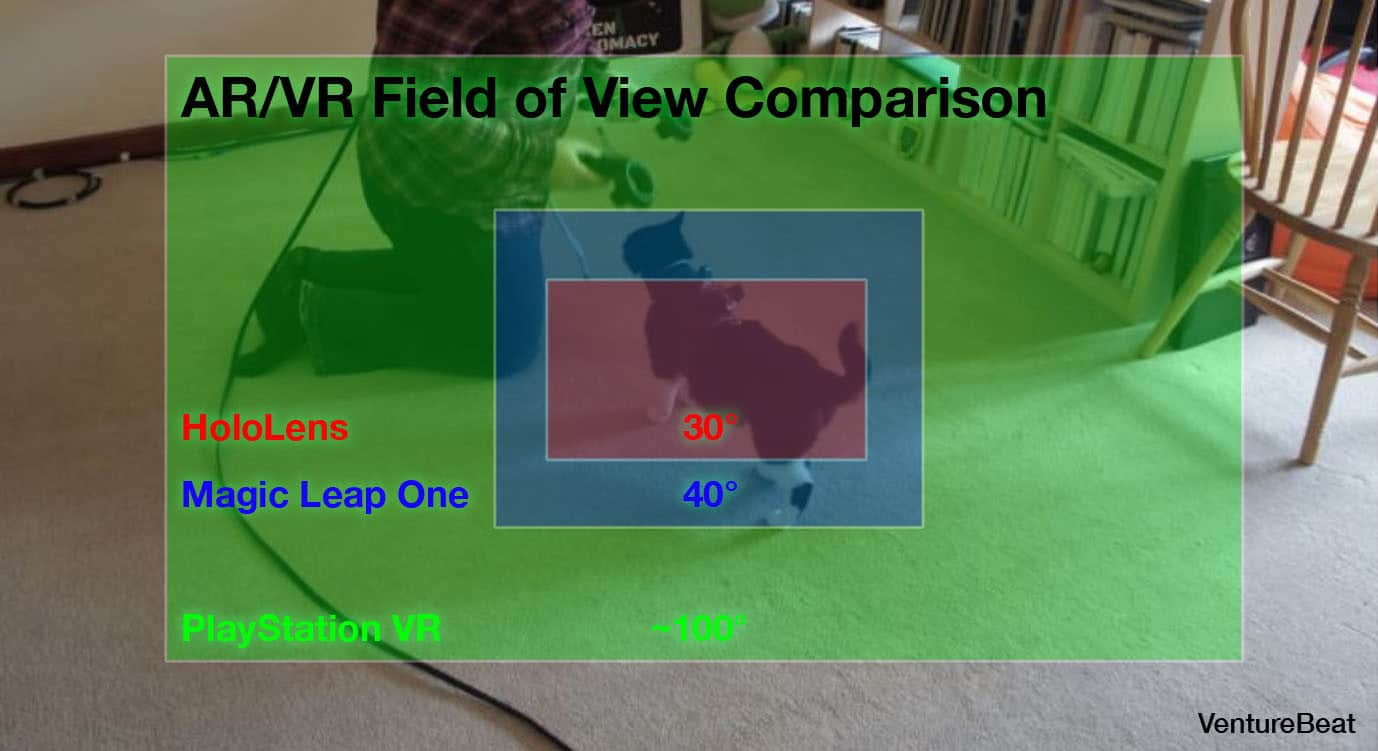

So with a headset based on Half Dome you’d see more of a virtual world in your periphery than current VR headsets and your eyes might be more relaxed and able to see clearer objects up close. Compare this possible roadmap for VR headsets to what we’ve seen from AR.

The field of view on the original HoloLens AR headset is so limited that certain applications, like gaming, generally aren’t fun when you constantly see characters or objects getting cut off.

Magic Leap One improves field of view so wearers note the limitation less frequently. Microsoft’s next generation HoloLens, due in 2019, could improve the field of view further for AR. Does the next HoloLens also ditch the fixed focus display?

Indoor vs. Outdoor

There is a long way to go before AR and VR headsets can meet in a middle ground where one headset could be a dual-mode “mixed reality” device great for both use cases.

Something that often gets muddled in discussion of VR and AR is outdoor use. Current headsets don’t have tracking systems in place to make outdoor operation safe and reliable yet. I’m also not sure people will want to wear fanny packs filled with batteries in order to enjoy AR throughout their day. Plus, see-through AR displays are usually most effective indoors in relatively dimly lit locations. For all these reasons, using any headset outdoors is mostly an academic concept in 2018. The dream of “mixed reality” is one day for a single headset to turn from perfectly transparent (AR) to completely opaque (VR) with digital objects shown throughout its wearer’s entire field of view in either mode. But there are hard engineering problems to overcome.

One simple approach is to slap a sunglasses-like filter onto a transparent AR display, effectively turning it into a VR display at any moment. This quick fix won’t change the underlying optics and field of view, though, or reduce the needs of power-hungry tracking systems which are necessary to establish a sense of safety and confidence for the person wearing a headset.

Fixed focus VR displays, though, like the kind popularized in part by Luckey and Oculus, are very cheap and work great indoors. You could turn the lights out and dance in the dark with an Oculus Rift on and you could still feel like you’re standing on the beach on a sunny day. Facebook’s Half Dome might be years away from transformation into something consumer ready, but by increasing field of view, and adding both eye-tracking and variable focus to a VR headset, Facebook is showing that it is effectively trying to engineer the perfect display technology specifically for VR and indoor use.

Magic Leap raised more than $2 billion over the last six years or so, to some degree, by promising a revolution to AR optics by way of a “photonic light field chip” and a whale that could fill a gymnasium.

But that’s not Magic Leap One, and it is not clear how Magic Leap Two or Three would improve things. Instead of a whale, you can enjoy a small car darting around your room with Magic Leap One. The car is likely to keep you so interested in its movements that you’ll never notice the edge of the display as it darts around directly in front of you. That’s about the best an AR headset can do in 2018.

this “Drive” developer sample is quickly becoming a favorite among new leapers… no idea why it wasn’t included in ML1! pic.twitter.com/PCRWbmbxDI

— andrés ornelas ?? (@andres) August 24, 2018

Don’t Use Mixed Reality When You Mean AR or VR

Some investors and entrepreneurs remain entranced by the potential of AR headsets to change the way we carry out our everyday lives both inside and outside our homes. Luckey seems to think it is these people — not developers — who represent the bulk of the folks buying Magic Leap One. That partially explains why Luckey refers to Magic Leap One as a “Tragic Heap.” For years, Magic Leap’s CEO Rony Abovitz raised money to build this headset while complaining publicly about the optics of current VR systems and promising a “photonic lightfield chip” to leap ahead of the market. Even now. Abovitz claims their headset “utilizes our unique optics to correct issues found in classic stereoscopic systems.”

Well the time for Magic Leap hype is over. Language like Abovitz uses might be good at raising money for a startup, but it does little to lure true developers into making a $2,300 purchase. It looks like Magic Leap One is a solid AR developer kit but there’s nothing magical about these optics and enthusiasm for AR shouldn’t come at the expense of a clear picture of the overall market. The perfect AR display remains elusive just as the perfect VR display is still only a concept. In the meantime, lots of people using the terms “XR” or “Mixed Reality” to describe the market as one single thing may be doing themselves and others a disservice by oversimplifying things too early.

What’s important to remember is that Mark Zuckerberg’s 2014 acquisition of Oculus has already seen the release of three completely different consumer VR headsets in an attempt to zero in on a gadget that is compelling to both developers and buyers. We expect that gadget to arrive in Q1 2019, precisely when Magic Leap should be thinking about how it can raise more money to build successive generations with a better field of view and a better outdoor tracking system. Facebook has the personal information of billions of people to target the sale of ads against, helping to fund the development of next generation technology. Even with its billions raised so far, though, I’m doubtful Magic Leap has the cash necessary to develop a headset delivering on the true promise of “mixed reality”.

While Magic Leap is delivering one of the first headsets on the market with eye-tracking built into every device, it won’t be the last. Eye-tracking is looking like it will be critical to major advances in AR and VR optics, cost and usability, but it also comes with enormous privacy risks.