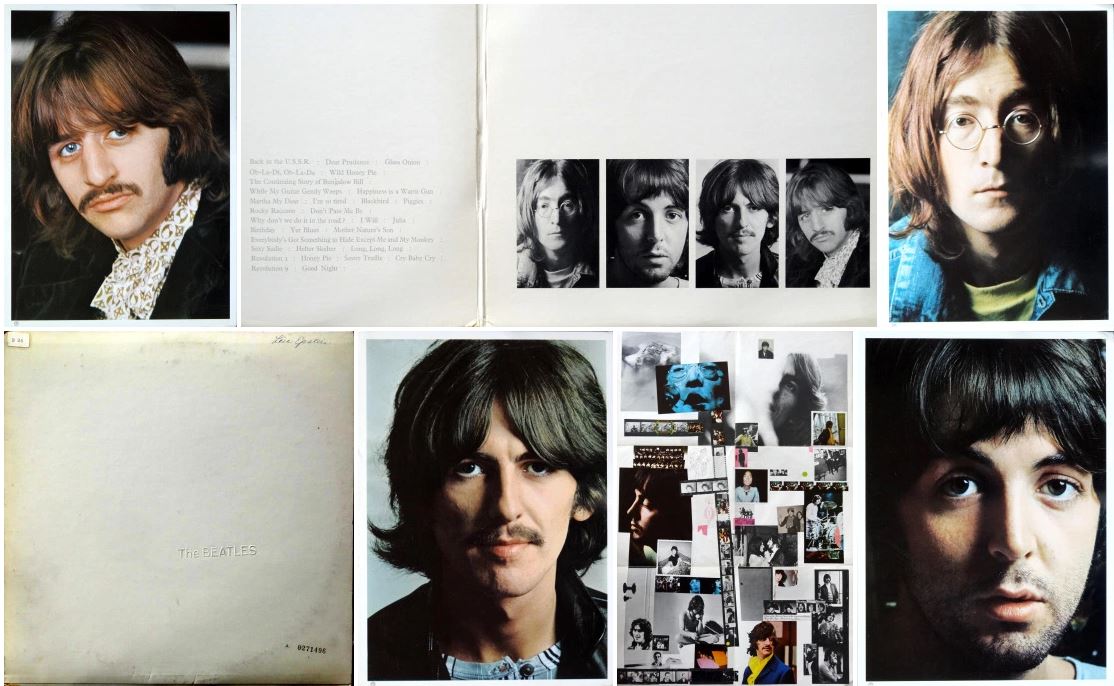

Reach into the front sleeve of the Beatles’ White Album (1968), and you’ll find four glossy, high-quality prints—portraits of the late George Harrison and John Lennon, as well as those of Sir Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr. They are the sort of photographs you might see on the cover of a late-’60s issue of Rolling Stone; in fact, two of them can be found on the John Lennon and Paul McCartney special collector’s editions of the magazine from 2012 and ’13, respectively. The Harrison image appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone issue 887, to commemorate the musician’s death in 2002.

The foldout in the back sleeve, however, is something that would be utterly alien to listeners of a certain age today.

Portals to the Past

Eschewing the more traditional style of liner notes, the front of the foldout centers on an artful semi-portrait of Harrison, much of his face having been burned away by darkroom wizardry of some kind. His one-eyed gaze is piercing, a beautifully grainy artifact of black-and-white photography almost half a century removed from the era of iTunes, Spotify, and YouTube. At the top is a 35-mm portrait of Lennon—plainly ironic, as he’s dressed like a university student and sporting a haircut that predates The White Album by roughly a decade. In the lower right-hand corner, there’s a snapshot of Ringo wearing a dark blue sport coat and ruffled yellow shirt, shades over his eyes, the composition framed by a wall of windows and painted white beams.

McCartney is shown in the bottom-leftmost corner, arguably the smallest of the portraits in this collage. It’s compositionally sound, even beautiful, but it also appears to be the least-rehearsed shot on the LP-sized sheet: in profile, mid-performance, McCartney seemingly unaware his photograph’s being taken. The singer-songwriter stands at the microphone, arms extended outward, his shirt alone hastily hand-colored in yellow pastel, as if to match Ringo’s.

Open it up, and it only gets richer from there—a trove of kaleidoscopic, timeless images of the artists and their families, including Yoko Ono, as well as an ink drawing by Lennon, a lipstick imprint signed “I love you” in red pen, and strips of Kodak film negatives. Not to mention the lyrics to all 30 songs. There’s one particularly touching photo of Ringo dancing with a woman who looks to be his ex-wife, the late Maureen Cox Tigrett. And another shot, black and white, of McCartney shampooing his hair in the bathtub, soapy water obscuring him from the neck down like a ghostly fog.

Losing Liner Notes

Apple Music, iTunes, Spotify—none of these services, however well-intentioned, can provide the listening experience of a phonograph and vinyl record, let alone the textual journey of an album’s liner notes, or the kinds of playful and experimental photo collages to be found in the Beatles’ White Album. But we live in another time: the age of availability, convenience, and ease. We’re a long ways from ’68. Launch a Beatles album in Apple Music, and what you’ll see is a list of tracks, an image of the band, and a single paragraph labeled “Editors’ Notes,” probably written within the last decade. There’s also a five-and-a-half-minute documentary, simply titled “The Beatles,” but even subscribers can’t access this. To watch the video, you have to purchase the record individually.

Ask most any audiophile, and they’ll lament the loss of liner notes. What we gain in the proliferation of digital content comes at the cost of a great degree of intimacy; music instead gets packaged as a mere collection of sound files—which, to an extent, it always has. But an album is an object, symbolic of a greater artistic whole. The Beatles understood this.

It’s fitting, then, that Sir Paul McCartney has been one of the first high-profile artists in the industry to embrace virtual reality as a means of recapturing that lost connection with audiences.

Back in August 2014, the team at Jaunt, a Palo Alto start-up “pioneering the future of creative storytelling through cinematic virtual reality,” joined McCartney onstage at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park to capture a live performance of “Live and Let Die.” The 360-degree VR experience that resulted was met with a positive reception.

“It was an amazing way to document a pivotal moment in his career so he could continue sharing it with his fans long after the tour had wrapped,” says Lucas Wilson, executive producer on Pure McCartney VR at Jaunt. “His fans loved it, our viewers loved it, and ever since we’ve been thinking about how we could work together again. When we learned of his upcoming album launch, we got back in touch with Paul’s team and pitched a number of ideas.”

Recapturing the Intimacy of Music

Pure McCartney VR is a new six-part documentary series that takes listeners behind the scenes of some of McCartney’s favorite songs and music videos from his five-decade solo career. “This concept of connecting personally with Paul, to learn about the stories behind the songs, really resonated with him,” Wilson tells me. “We sent a team to shoot in his private home studio, and we couldn’t be happier to bring the final result to fans.”

“Coming Up,” the first of the Pure McCartney VR shorts, finds McCartney sitting behind the drum kit, recounting both the songwriting process and the production of the original 1980 music video, which debuted on the BBC’s Top of the Pops. He explains the process of laying down the rhythm-section parts, and then points out the inspirations for a number of the characters he portrayed in the video, from the Shadows’ Hank Marvin to the late John Bonham. The high-definition footage of the studio is augmented with digital 2D “screens,” which serve as a visual guide to the artist’s commentary on the song. It’s a lovely, insightful, three-minute glimpse into the making of the McCartney II single.

The second video in the series—also directed by Tony Kaye, with soundscape design by Geoff Emerick—begins with an anecdote about McCartney’s favorite London guitar shop, where, on a whim, he purchased the left-handed mandolin that inspired the 2007 tune “Dance Tonight.” As he tells this story, the musician’s studio transitions from a surreal, cartoonish rendition of London to a cascade of hand-drawn chord charts. McCartney recalls inviting Natalie Portman over the phone to appear in the music video, and then asking French filmmaker Michel Gondry to direct it, though the focus soon shifts back to the songwriting process.

So what makes virtual reality the ideal replacement for the liner notes of yesteryear?

“Today’s most innovative artists are always looking for new ways to push boundaries, with their music and their means of connecting with fans,” says Wilson. “As VR is seeing increasing consumer adoption, it’s providing artists and entertainers of all sorts an entirely new avenue. We’re used to going to concerts, but very few of us have actually been on stage. We’ve grown accustomed to hearing from our favorite artists on social media, but rarely do those words come directly from their mouths. VR is changing all that. It’s the most personal way of connecting with your fans.”

Wilson says he thinks behind-the-scenes features like Pure McCartney VR will become one of the dominant applications for virtual reality in music, though there’s no reason to think that interactive music videos won’t be just as common. “Since the days of the Lumière brothers, cinematographers have dealt with new tools and methods for recording images. But whether it’s a new camera or lens, a new format, or an entirely new technology, the art of directing and cinematography does not change. The tools do.” He also notes the challenges directors face as experimentation with the technology opens up new ways of working in the medium.

“Viewers can turn in any direction, at any time, to see what they want to see. The real challenge is finding the right balance,” says Wilson. “Providing viewers with enough entertainment all around them, while still trying to get your vision across. With these McCartney videos, we achieved this by of course having Paul front and center, but fans can also look around his actual studio, see flashes of music videos, still photos, and more, all to supplement the memories he’s recounting at the time.”

As an almost lifelong fan of McCartney’s music, there’s one last question I can’t help asking: will we see more virtual reality content from the former Beatle? “He’s certainly one of the most creative people we’ve ever worked with, and a true pioneer in terms of VR entertainment,” Wilson replies. “He’s constantly pushing the envelope.”

—

Alex Kane is a freelance writer with work appearing in outlets such as Killscreen and Versions. You can follow him on Twitter: @alexjkane.