I’m standing on a cliff high up overlooking mountainous horizon of the Himalayas, the air swirling all around me. As I turn around, I see an iron door to my left and a golden statue to my right. No on-screen prompts, no instructions, I am simply thrust into the experience. Seconds tick by and as the beauty of the scene settles in, my mind begins to turn to the question: What is my purpose in this world? That question lies at the very heart of Thunderbird, a new game coming to the HTC Vive and PSVR from the father-son team at Innervision VR.

“Virtual Reality has the innate ability to mimic reality,” says Tony Davidson, Innervision VR’s founder. “When someone first puts on a VR headset they are instantly transported to another reality where they are forced to reckon with their existential state of being.” That’s why games like Thunderbird, which takes inspiration from titles like Myst and Riven (a title that he was heavily involved with), work so well for VR. It forces you to seek the meaning for yourself, while appreciating the detail of the world that you are in.

Thunderbird is based on myths that transcend multiple different cultures, from Native Americans to the people of the Himalayas. The game takes the player on a journey to find a mysterious secret hidden deep in the depths of a sacred caldera in the mountains.

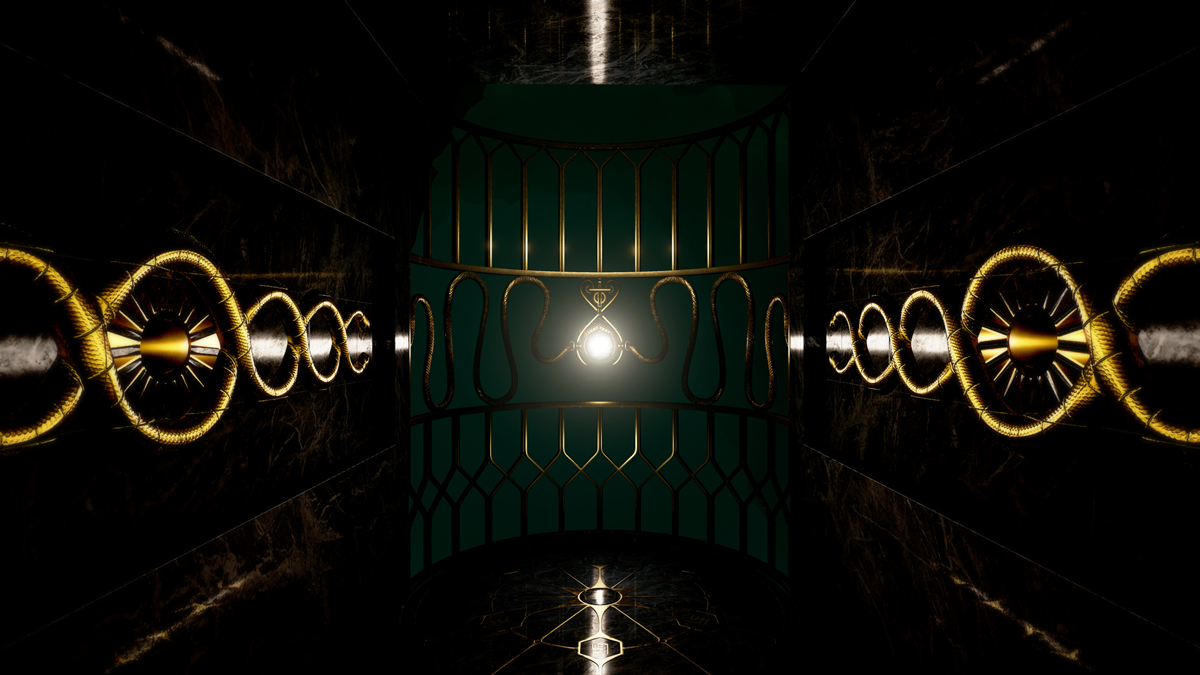

Davidson describes Thunderbird as a hybridization between a game and a cinematic experience. At the beginning, there is a strong emphasis on puzzles and interaction with the scenes, but that changes as the story unfolds. “At the core of the experience,” says Davidson “we are trying to carry the player from a more mundane reality to a fantastical one… [which will] culminate in a more cinematic and passive experience.” As you uncover the mysteries of Thunderbird the game will “lead you to the heart of the world for an encounter with mythological creatures of epic proportions” bringing these legends to life.

Thunderbird might as well have been codenamed phoenix, as it rose from the ashes of Innervision’s previous VR project, Ethereon.

“Ethereon was fundamentally flawed at its core,” Davidson admits. “What I was trying to accomplish with that I realized was not quite possible,” citing traversing vast landscapes as a major roadblock. “We learned so much [from Ethereon] and wanted to just start fresh,” he says. A lot of the original ideas and concepts from Ethereon have been found their way into Thunderbird but in a far more refined way. For example, locomotion in Thunderbird utilizes two different modes, a full room scale version with scenes designed to take place within the playable space, as well as a version with a point and teleport system for people with smaller play spaces or on the PSVR (which isn’t nearly as equipped for room scale experiences).

The addition of hand-tracked controllers takes Thunderbird to the next level. Whereas experiences like Myst utilized a point and click mechanic, Thunderbird allows the player to interact with puzzles in an entirely new way, opening up a number of interesting possibilities.

In my hands-on with the game’s first series of puzzles (portrayed in the video above) I was extremely impressed with just how much immersion this interactivity lent to the style of game. The idea of Presence in VR is somewhat ephemeral, one that only is achieved when a VR experience immerses with more than just incredible visuals. The way that Thunderbird builds this with interaction and storytelling is profound, creating an experience that has been burned into my mind since the moment I first had a chance to explore it. In a way, Thunderbird beckons the player into finding that sense of Presence in a world filled with myth and wonder.

“The first time I saw VR on the cover of a magazine,” Davidson says, “that literally changed my life, it gave me a sense of purpose.”

The essence of discovery in games on a new medium isn’t new. In 1993, the CD-ROM was a relatively new format for video games. It brought with it greater a storage capacity, which opened the door for amazing new experiences but it was still a nascent technology that was slow in its early adoption until Myst was released.

Myst is widely given credit for accelerating the adoption of the CD-ROM format. In fact, according Davidson, Cyan received a letter from none other than Steve Jobs thanking the Myst team for “the success of the CD-ROM for the Mac at a time when they were flopping and just about to pull the units off the market.” The game’s success wasn’t a fluke; it had to do with the level of immersion it brought to the player.

“What made experiences like Myst and Riven so unique and successful,” he says, “was their very strong emphasis on immersing you into another reality. “ The advancement of the CD-ROM and subsequently the DVD allowed Cyan to create “a more compelling experience than was possible before” bringing with it “a whole new level of immersion.” Something Davidson likens to the advancement of virtual reality today.

“I’m a firm believer that the ones to embrace VR will be the non-gamers who are looking for something more than what conventional games have been able to offer in the past,” he says.

The Story Behind the Game

Beyond its beauty and structure, perhaps one of the most amazing things about Thunderbird is the story behind its creators, a two-man father-son team, and its creation.

Passion lies at the center of Innervision’s story, as Thunderbird is completely self-funded. According to Davidson he “put everything he has,” into making the game, including time, logging over 13,000 hours of VR development in the last three years. But all the time and money is worth it, he says, to create “something meaningful.”

Tony Davidson describes his early life in central Arkansas to have been “mundane.” He was sweeping chimneys for a living when he first learned about VR in 1993.

“The first time I saw VR on the cover of a magazine,” he says, “that literally changed my life, it gave me a sense of purpose.”

Filled with a desire to create immersive worlds, Davidson headed to the Raliegh School of Arts in 1993 to take a three-month course on 3D computer graphic development. The work he created in that course led to him being discovered by Robyn and Rand Miller, the co-founders of Cyan. Impressed by his work, they brought him on to work as one of the lead artists on Riven, which eventually would go on to become the best-selling game of 1997. But Davidson’s passion was always VR, and the technology simply was not ready for his visions at the time, so he eventually moved on from gaming to work at Dreamworks on movies like How to Train Your Dragon and Madagascar: Escape2Africa.

When the DK1 was announced, he was among the first to get on board with VR’s second coming. Davidson started work on Ethereon, a project that he describes as being the result of, “those 20-year-old concepts that I had imagined back then from my first exposure to VR.” When the project’s Kickstarter failed to gain traction, Tony and his son Kai returned to the drawing board.

Unlike Tony Davidson, his son was “raised an artist,” starting work with 3D computer graphics at eight years old. Now 17, Kai Davidson has developed into a bit of a prodigy in the medium, so much so that he is taking more of the lead role in Thunderbird’s art direction, leaving Tony to focus on the technical aspects.

“I rely on him,” says Tony Davidson, “we are very much so co-directing it.”

The game’s inspiration came from a dream Kai had after a lackluster response to the showing of Ethereon at VRLA in December of 2014. On their long car ride back to Oregon, Kai began recounting a dream he had about a large emerald cave at the top of a mountain. The dream sparked a long brainstorming session that stretched into the night as the two traveled home, by the end of the drive the main conceptualization for Thunderbird was locked down and the two started development in earnest March, 2015.

As inspiring as Thunderbird’s story is, it would be meaningless if the experience itself wasn’t equally so. In the twenty minutes or so I spent in Thunderbird were among the best I have spent in VR. The experience hits on everything that makes the medium so incredible with an emphasis on guiding the player through an impossible experience with the meticulous attention to detail required of a top-class VR experience.

While the game was inspired by great titles like Myst and Riven, it has the potential to become what they ultimately were meant to be: a game that completely transports you into a world you never believed possible.

Thunderbird will be released in three to four chapters on the HTC Vive and PSVR with the first, Thunderbird: The Legend Begins, coming “sometime this summer.” According to the team, the rest of the chapters (which will run “at least an hour in length”) will follow with a release cycle of about four to six months.