Passionate discussion and art are longtime bedfellows—and for good reason. Artists and critics alike tend to care a great deal about their work, and have strong opinions about the language we should use to discuss it. But when impassioned debate tips into bitter argument, divisions are born that potentially hurt all involved parties.

This year, I’ve heard increasingly heated discussion surrounding 360° cinema’s “right” to be called “True VR.” More often than not, what I find is that resentments and negative language are cluttering conversations among those who, in theory, have the same goal: to create amazing new content in amazing new formats, so it seemed like time for an olive branch.

In case all of the above is Greek to you, here are the basics:

360° cinema is live-action video shot on a 360° camera or rig. When a viewer dons a headset to watch a 360° experience, choosing where to look, and feeling immersed in the footage itself, is the extent of possible interaction. The story is set in stone—in theory, nothing the viewer does will change the plot of a given 360° video. Lite interactivity has happened recently with experiences like GONE and VR Noir, but the events are all pre-scripted. You can’t actually influence or change anything, really.

The premise behind the “True VR” purist camp is that 360° cinema lacks the necessary degree of interactivity and depth to create a true virtual reality. In a fully virtual experience, viewer interaction actually impacts the plot of the piece. In this format, VR is volumetric and responsive. Where it involves “live-action” is photo- or videogrammetry—capturing live subjects from many different angles simultaneously to produce a computer-generated replication. Inside the headset, these replications suffer no loss in visual clarity from any angle or vantage point. 360° footage suffers from the shortcomings of a typical camera—something farther away will lack detail, and possibly appear out of focus. You certainly cannot reconstruct an environment from a different vantage point. However it was filmed is how it will be presented.

Moreover, since much of VR is still centered around video game experiences, in “True VR,” artists build characters, objects, and environments in a game engine like Unity or Unreal Engine, which further expands the ability to fracture, branch, and reiterate a narrative. Plot is responsive to (and indeed dependent on) user engagement; participators are granted the chance to interact and explore in a way that 360° video simply does not afford.

Read More: Virtual Reality Still Needs to Find Its Heart

“360 apologists” argue that, though their story experiences may be pre-ordained, the immersive nature of their environments and the realism achieved does cut VR-mustard—what matters is ensuring a seamless sensory environment for viewers to perceive. Though there’ll be plenty of instances where a novice plops down a 360° camera to make an immersive video, in its ideal form, a 360° cinema is conceived with an entire writing and pre-production process akin to film. The success of the story is dependent on an artist’s ability to previsualize the best possible way to showcase their experience in the given environment(s).

Moreover, the apologists claim the argument that 360° video fails to achieve “True” VR is unnecessarily divisive because it stifles creativity within the community.

This might seem like a semantic discussion, and in a sense it is, but VR is (finally) departing the realm of novelty for the promised land of mainstream adoption. The language we build for it now will have a direct impact on the growth of these two emerging genres, which can determine how they grow and what they become.

As a pragmatist, I see three problems in this discussion: (1) It is framed as a fight: there are attackers (purists) and attacked (apologists,) (2) There’s a misunderstanding of “genre” and “medium,” (3) There’s disagreement over what constitutes the minimum amount of interactivity to be considered authentic VR.

We can address the first issue quite easily by changing the language we use. Instead of “True VR,” I propose we call it “Responsive VR.” This term honors the form’s unique capabilities without inherently indicting the validity of 360° cinema’s place alongside it. It is also broad enough to include the spectrum from active gaming to invisible interactivity.

As to the second issue, what if instead of talking about the ways these are different mediums we talked about the ways they are different genres within the same medium. I don’t criticize a comedy for not being a documentary. Why not do the same in this case? That way we could take a more level-headed look at their differences while simultaneously honoring their many commonalities.

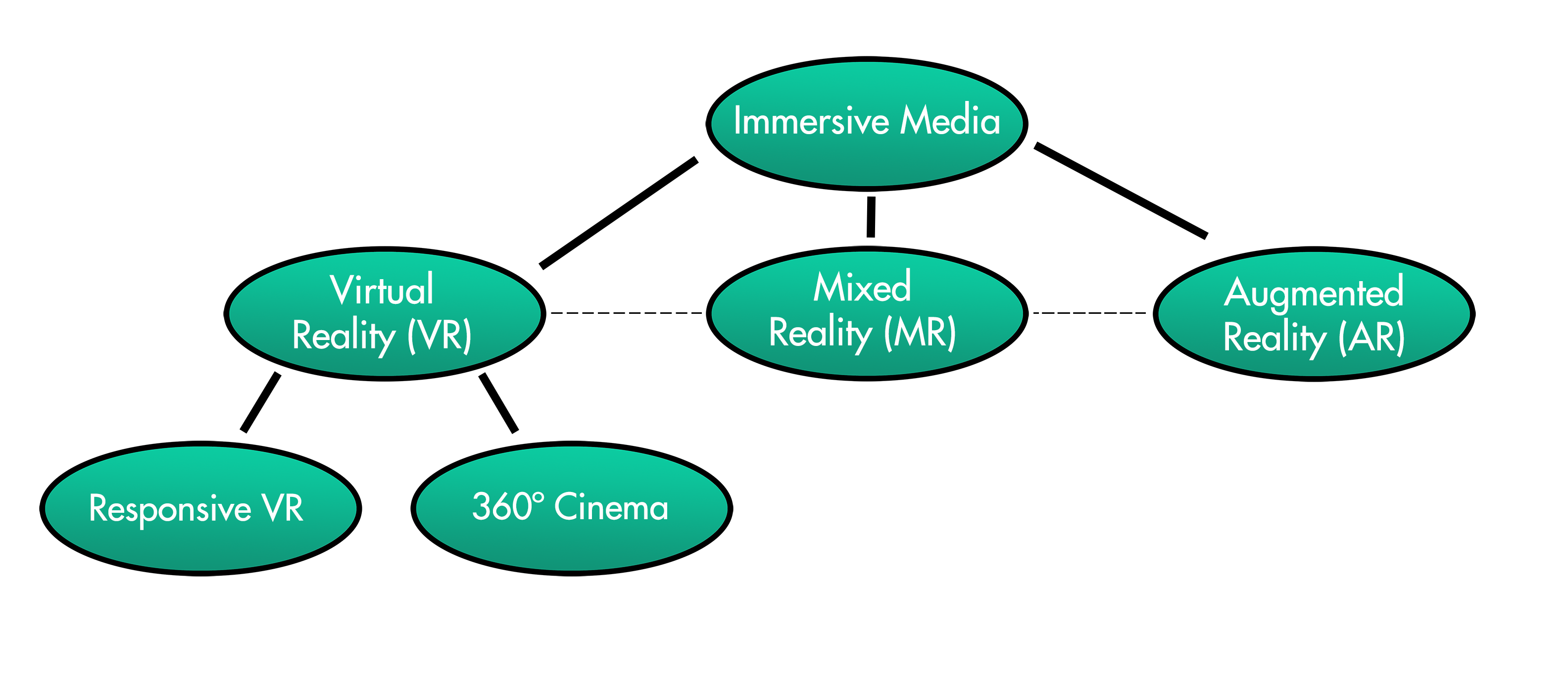

Because ultimately, they are the same medium. In the “Family Tree of Immersive Media,” they are both virtual realities—simulated environments altogether different than the one we are physically inhabiting. They’re even viewed using the same hardware.

So I personally propose a new “Family Tree of Immersive Media” that looks like this:

You might say to yourself, “Why do taxonomies matter? Just make what you want!” And of course there’s truth to that, but the language and hierarchies we use to discuss media can actually change their development.

An example I’d pull from history is television, which for decades was treated and spoken of as an inferior form to film. Over time, this determined what audiences expected from TV, and this created a feedback loop; television networks catered to audience expectations, which in turn meant that much of TV actually did become frivolous, escapist, or passing in nature—the ambitious artists who might have been able to produce cutting-edge work were often rejected.

Community Download: Should 360 Videos Be Considered “Real” VR?

It took decades for these artists to showcase their work in television. Of course, now we see that television is actually a great home for “high” art—it’s home to some of the most thorough visual narrative emerging from the Western world. Since VR is such an exciting new medium, let’s not silo any group into being somehow “lesser.” Why not make space for everybody to create the most amazing art possible in whatever format they want?

The interactivity issue is much more complicated. Determining a baseline level of interactivity to be considered “authentic” virtual reality is not only impossible, it’s nearsighted to bother trying. Gray areas are already emerging on the spectrum between 360° cinema and Responsive VR, and this will only become truer as time passes. Why draw boundaries between genres in a medium designed to converge and bring together? Let’s leave ample space for everybody in our family tree.

Are 360° Cinema and Responsive VR different? Absolutely. Is either superior to the other? Absolutely not. The goal for all of us should be to find ways to use this new technology to make the newest, coolest, most innovative work we possibly can. Let’s enable each other to explore this territory to its fullest. Nobody has to be on the losing end of this revolution.

—

Jesse is a freelance writer with work appearing in publications such as The Huffington Post and IndieWire. Follow him on Twitter: @JesseDamiani.

Featured Image: Samsung