At CES in Las Vegas we saw a collection of next-generation technologies. Wireless, super high resolutions and eye-tracking all showed potential to dramatically improve future VR headsets.

Each of these technologies, however, was shown in separate demos. What happens when a company like Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Amazon or Apple starts to put all these things together? If they can lower the overall cost of a VR system while simultaneously improving the feeling of immersion, that’s a recipe for bringing tens of millions of new customers into VR.

In 2018, we’ll see wireless, eye-tracking and higher resolution headsets like the Vive Pro, but we aren’t seeing all these things offered together in a single relatively low cost package. We hope it happens this year, but more likely we’ll see it in 2019. This post is meant to show what a VR headset next year might look like.

Manufacturers, of course, have to grapple with a lot of trade-offs in designing hardware. As engineers dive into the specifics of wireless standards, eye-tracking solutions and the capabilities of ultra high resolution displays, they could encounter roadblocks that might make these technologies harder to implement together. Nonetheless, we know the world’s biggest tech companies are working to solve these problems and all the things I’m writing about are already up and running inside VR headsets. So here’s a look at what might happen come 2019.

Eye-Tracking

The region directly in front of your eyes sees the greatest detail. It is how humans observe the world in such clarity. Outside that circle, though, there’s your periphery. Things can catch your eye in your periphery but you can’t see them with perfect clarity there. Instead, your eyes catch an object in the periphery and then point directly at it to get that extra bit of detail.

The region directly in front of your eyes sees the greatest detail. It is how humans observe the world in such clarity. Outside that circle, though, there’s your periphery. Things can catch your eye in your periphery but you can’t see them with perfect clarity there. Instead, your eyes catch an object in the periphery and then point directly at it to get that extra bit of detail.

Eye-tracking in a VR headset can use this knowledge to do something called “foveated rendering” which more efficiently delivers visuals to your eyes. The system will render the greatest detail directly in front of your eyeballs with less detail drawn in your periphery. This can only be done if the headset knows where your eyes are pointed, thus eye-tracking would likely be a key component of next generation headsets. Apple bought eye-tracking company SMI last year, effectively validating the technology while forcing others working with SMI to find another solution to use like Tobii.

Eye-tracking enhances social interactions in VR, and completely changes the way you interact with virtual objects. The time it takes to complete most tasks in VR can also be reduced by using your eyes to target exactly what you want.

The biggest benefit of eye-tracking, however, is what it means for the bottom line — cost.

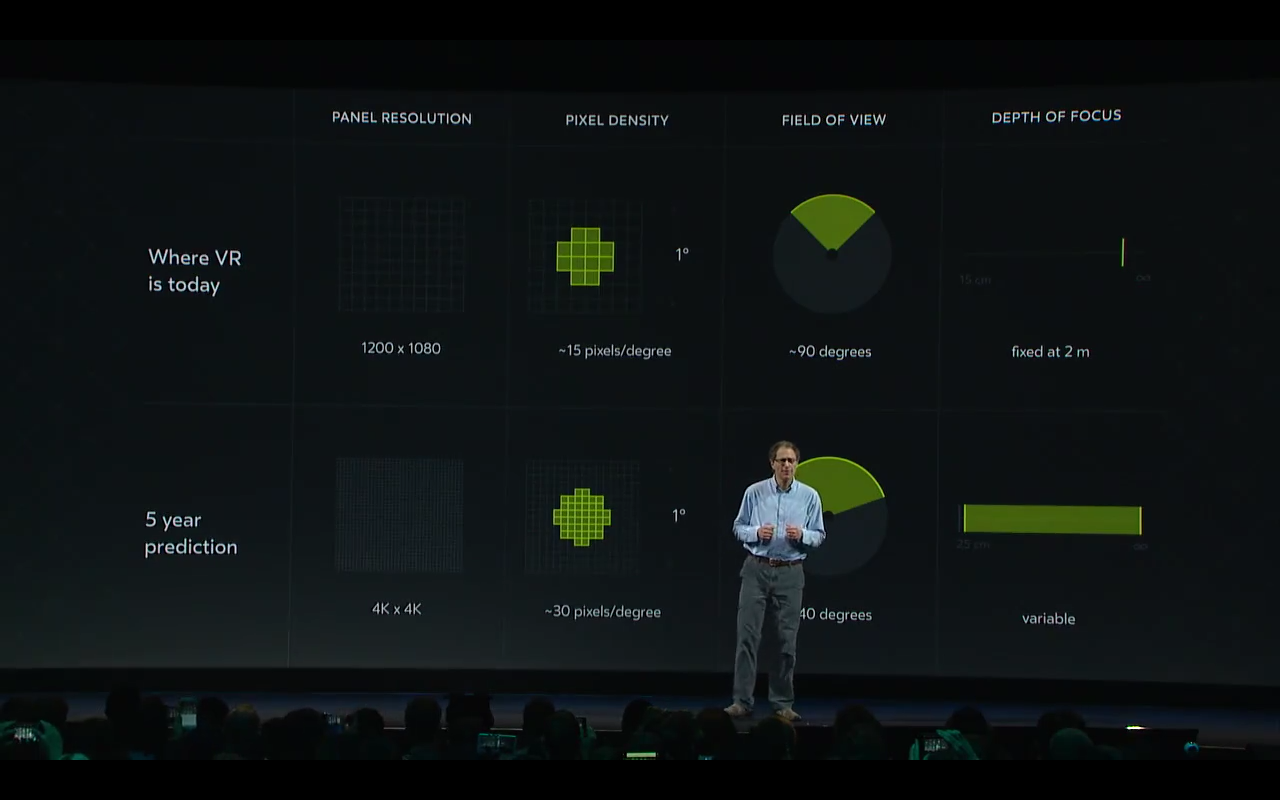

Higher Resolutions

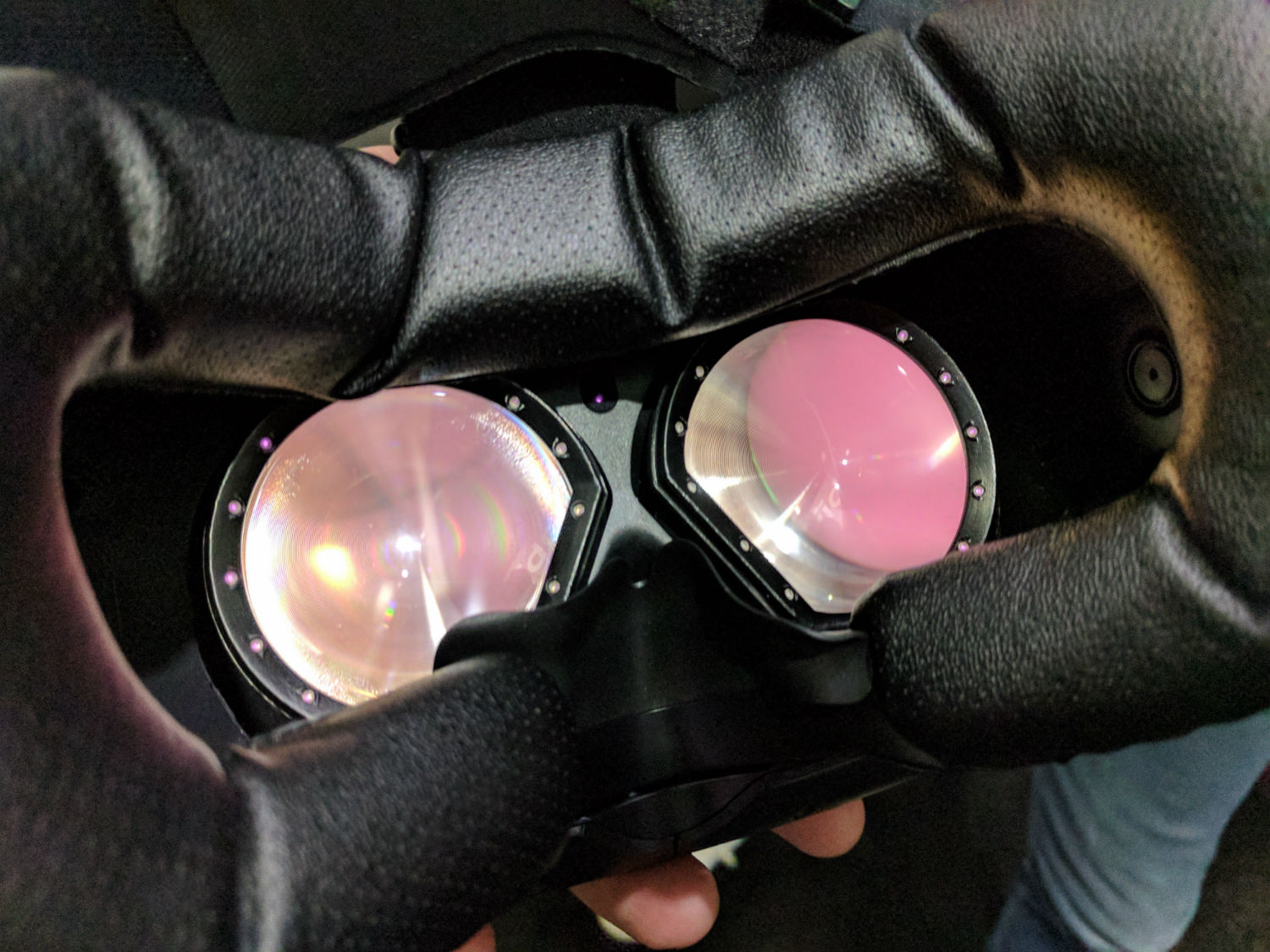

If you’ve ever complained about the “screen door” effect of current VR headsets — where you can see the individual pixels — then you’ll be very happy to try the Samsung Odyssey or upcoming Vive Pro. Their 1440 x 1600 per eye displays reduce the feeling that you’re seeing a virtual world through the squares of a screen door. These headsets, however, don’t completely eliminate the feeling. It is looking like we might have to wait until at least 2019 for great headsets to take another big jump in resolution.

So far VR headset manufacturers have been fairly reliant on Samsung as a supplier of high performance OLED displays, but other companies are itching to provide their solutions for VR headsets as well. One such company, Kopin, showed a 2,000 x 2,000 pixel per eye microdisplay running at 60 frames per second at CES. While 60 frames flashing in front of your eyes doesn’t quite match the smoothness you’ll notice with the 90 frames seen each second in a Rift or Vive, Kopin representatives seem confident they can make their displays run at a higher frame rate.

No matter whether it is Kopin, Varjo or some other company delivering higher resolutions to VR headsets, we are only likely to see these improvements if the headsets also include eye-tracking. Foveated rendering will be critical to making the resolution jump affordable because it’ll allow system architects to use lower cost graphics cards to draw the greatest detail only where you’ll notice it — directly in front of your eyeballs. If the manufacturer is already paying more money to put a higher resolution display inside a future VR headset, getting back some of that cost by using less expensive graphics cards could be absolutely critical.

Lower Cost

It is arguably not a “feature”, but lowering the all-in cost of future VR systems is likely the most important advancement any company can achieve.

Facebook’s Oculus Go starts at just $200 — an incredible starting point for a mostly sit-down VR experience — while standalone headsets like the upcoming Lenovo Mirage Solo start under $400 for an experience that allows full freedom of movement for your head, but only limited freedom for your hands.

People, however, need full freedom of movement for their hands to have a truly interactive experience. That’s what Oculus showed with its latest Santa Cruz prototype in October — an all-in-one VR headset with crisp visuals and flexible hand controllers. The careful camera placement on the headset meant they even worked when I tried grabbing a virtual object behind me, without looking at it. Is Facebook willing to take a loss on a consumer version of such a device in 2019 in order to reach more people? A standalone VR headset with graphics, battery, tracking, display and great full freedom controllers is an amazing prospect — but being able to keep all of it low cost would be a true test of design skill, and it would take some leadership risk.

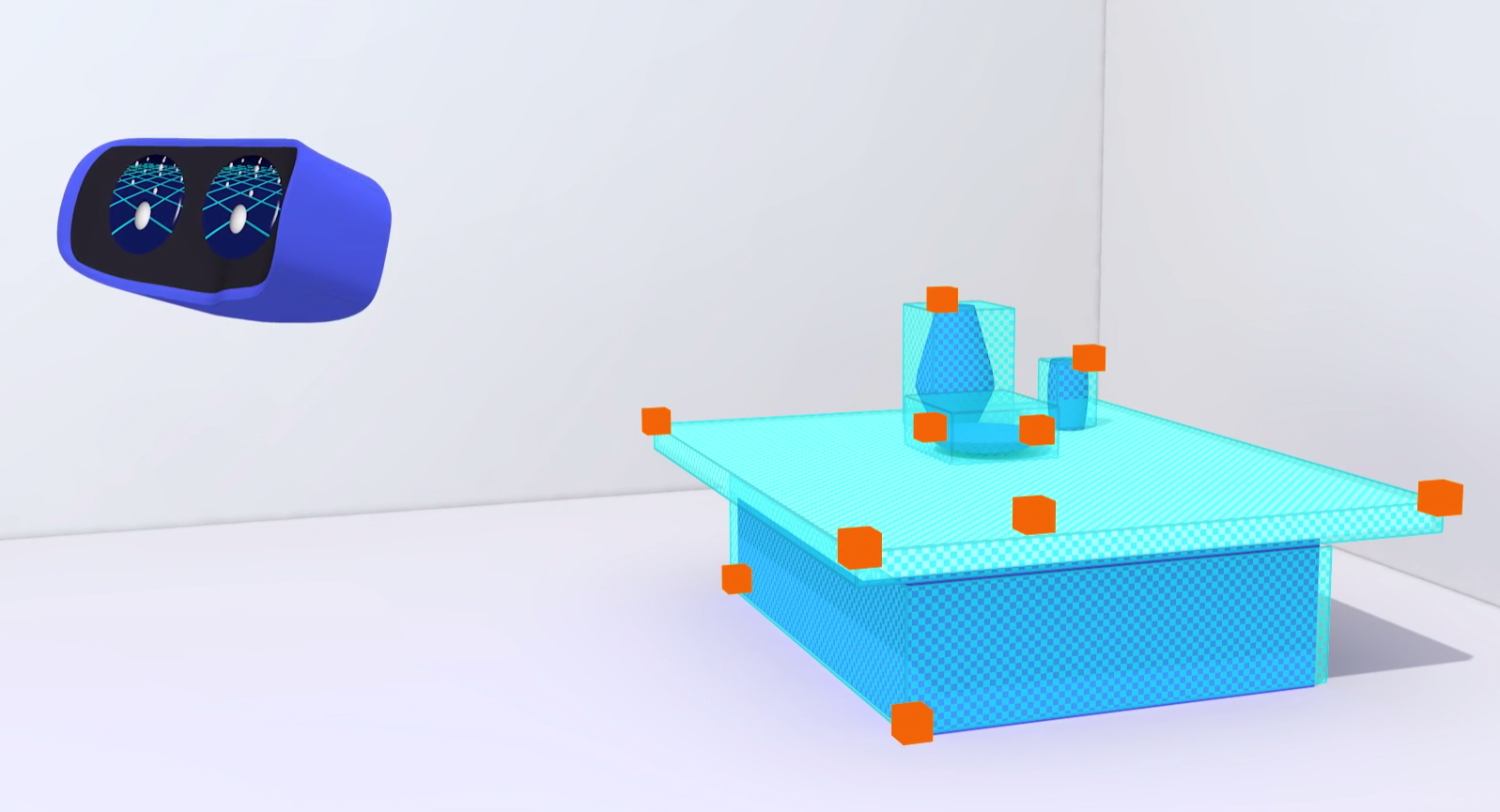

Inside-Out Tracking

Microsoft has a major lead with this technology. VR headsets powered by its tracking are selling as low as $215 on Amazon as of this writing. The headsets still require a relatively expensive high-powered PC connected by a cord to work right now, but they are a major step forward from Rift and Vive in terms of convenience. The cameras on-board each of these headsets see the world around to figure out its precise position. These cameras also see controllers so you’ve got increased immersion and interactivity. With Rift and Vive, which first shipped in 2016, you have to install cameras or lasers around the outside of the room to do this.

With Santa Cruz, Facebook showed its version of inside-out tracking is catching up fast. Meanwhile, Google is powering the Lenovo headset and Qualcomm offers core tracking technology it can share with other manufacturers like HTC.

Inside-out tracking offers an important jump in convenience that will be critical to broadening the appeal of VR, but we have yet to see it combined in a compelling package with hand controllers and one more critical feature — wireless.

Wireless

There are multiple paths to wireless headsets.

One approach is a high-powered processing box like a PC (or perhaps a console like an Xbox X) with a radio that broadcasts and receives a very large volume of data to and from a nearby VR headset. This approach adds a battery either to the headset or wired and clipped to your clothing.

Another approach — a standalone system — puts not just the battery but also the processing either in the headset or in a wired pack attached to your clothing.

The second approach is more portable while the first might be more cost effective for people who already invested in a PC or console capable of doing the hard work of drawing a virtual world.

Also, we have yet to see it yet, but advances with mobile phones might allow for yet another approach to wireless VR that brings together higher resolutions with great hand controllers.