If you squint, you can begin to glimpse the correlation; VR gaming, as tumultuous a time it has endured these past four years, is starting to make a little sense of itself.

Experiences are getting better and turning more profit as cheaper, more advanced headsets hit the market. Bigger studios are becoming increasingly enticed to jump in while early bets are paying off with acquisitions and publishing deals. It’s early days yet, but there’s the beginnings of a sense of closure for VR gaming’s Wild West-era. Outlaws are being rounded up and a new age of civilization is gradually being ushered in.

Look to VR movies, though, and the cowboys still run wild.

Enter Atlas V

While Valve, Facebook and Sony mainly cater to gamers, filmmakers continue to poke and prod at this new means of storytelling, fleshing out the rules and learnings in successive — if restrictive — loops of the annual festival circuit. Sundance, Tribeca, Venice and more come and go but are only just starting to open their doors to a wider audience in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. With no dedicated, definitive distribution platform to call its own, the VR movie scene is like a gang of bold bandits moving from one heist to the next. But they have a few ring leaders.

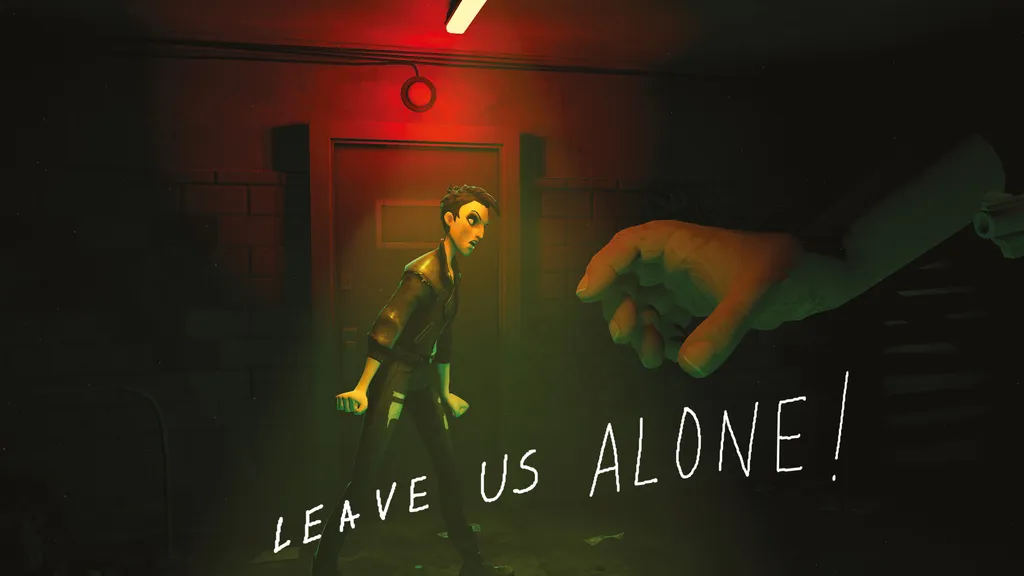

One name I see continuously attached to some of VR movie’s most exciting projects is Atlas V, a studio that offers services across the entire production pipeline. Over the past three or so years its work with directors and filmmakers has resulted in incredible curiosities like Martín Allais and Nico Casavecchia’s Battlescar, a blistering deep dive into New York’s 1970’s punk rock scene, and Gloomy Eyes, Fernando Maldonado and Jorge Tereso’s conflicting and cute zombie romance.

They’ve even helped make headlines – Eliza McNitt’s hypnotic Spheres landed a seven-figure deal after a 2018 Sundance showing and star talent like Daisy Ridley, Colin Farrell and Rosario Dawson have lent their voices to their projects. Just recently it hit Venice with the softly sweet Goodbye Mr. Octopus and a visually-stunning tease of Mirror: The Signal. In other words, Atlas V has its fingers in a heck of a lot of pies.

Antoine Cayrol is one of four co-founders behind the company. He’s been working in producing new wave media, including interactive video and more, for years. Around six or so years ago, meeting industry friends for drinks, he happened upon something new – a virtual reality headset someone had just been sent after backing a Kickstarter. There was a steady torrent of people putting the headset on and screaming their lungs out. Cayrol put the goggles on to find himself on a virtual rollercoaster – fertile ground for VR nausea for even the most experienced users. You could imagine what it would do to a first-timer that had just downed two shots of whiskey. Feeling faint and headed for air, he condemned his friend, artist Pierre Zandrowicz, to see it too.

Zandrowicz joined Cayrol outside five minutes later, the pair mirroring each other’s sickly-white expressions. As they recovered they came to a conclusion very different to that of most VR sickness sufferers. “We thought, if this thing can give you so much negative emotion then it must also be able to give you so much positive emotion,” Cayrol says.

From that rollercoaster, both literal and emotional, came the pair’s first VR production, a short 360-degree movie called I Philip. Building from that, Cayrol and Zandrowicz joined Arnaud Colinart and Fred Volhuer, to create Atlas V, a studio that views VR and AR storytelling as an almost logical step. “I think it all started with a vision,” Cayrol recounts. “And we share the same vision in that, spatial computing is more and more present. And, in a way, we know that if we are producing for the next decades, we’re coming towards the end of the screens as we know it. My children, they won’t watch the same things as I did.”

He acknowledges that transition won’t happen overnight, but Cayrol sees the rise of VR and AR as a key moment for other types of media that have lived in the shadow of cinema until now. “A lot of new wave entertainment, immersive theater etc, all this stuff is coming together. Before it was like you could either do a game or a movie, but now you can do both – something interactive, and we don’t don’t have to be jealous of feature films. It can look almost as good as a feature film.”

And so Atlas V set about working with creatives of all different kinds, building up a remarkable body of work in three short years. Collaborating with independent directors, the studio seems to possess an assured and rare understanding of the medium, something Cayrol attributes to the breadth of creators its worked with. “I think being involved with different kinds of people makes us grow a lot,” he says. “Because we use a lot of different techniques, a lot of different art direction. Some projects have big tech problems, some projects have big graphics problems, some have storytelling problems. And every time we solve new problems, because every project is different thanks to the artists.”

And there’s plenty to be solved, too. Something like Mirror: The Signal pushes graphical fidelity forward while the viewer looks on, whereas in Spheres they can experiment with the world around them to make it their own. Between interactive mechanics, perspectives and styles, VR filmmaking remains an unwieldy beast with much of its language still to be figured out.

The Business Of Showbusiness

No one could deny how impressive the portfolio is, but what’s always had me scratching my head about Atlas V and its contemporaries is the economics of it all. Whereas some other VR production studios have floundered and even closed their doors (including Facebook’s own Oculus Story Studio, which released free movies in the Rift-era) this group has continued to systematically grow. How do you do that with a consumer market that’s mainly orientated toward games?

“We tried to do what movie producers are doing and not what game producers are doing,” Cayrol says of keeping the lights on. “Game producers are really ballsy. They put their own money in to create a game and hope to sell a lot to create another one. And they can do that because there is a big, big market for the games industry. Even if you do a bad release you could do 100,000 units.”

“As we’re not doing gaming, we try and sell as a feature film producer. So what we do is, when we finance a movie, we need to finance a part of the company. So we know how much it costs for the company to work, we have 10 people, we have the space, internet, electricity etc. We know it costs this amount per year and we need to finance this with the project.”

In its first years, this worked by running the company purely on that financing, without much thought to revenue. Cayrol explains Atlas V first established its production side, which he describes as “less risky”. From that foundation came early co-production projects like Spheres (made alongside Crimes of Curiosity and Novelab), which was lauded for its poetic view of the universe and startling visualization of cosmic phenomena.

Since then, Atlas V has bolted on new features slowly but surely in the ensuing years. Last year, it revealed plans to distribute its content for location-based services and, earlier in 2020, followed through with publishing content either on its own like with the Steam launch of Ayahuasca or with partners, as seen in the Quest and Steam release of Gloomy Eyes or the upcoming launch of Battlescar. In May, the company announced Albyon, a new studio offering end-to-end production services.

“There is space to create an immersive media group,” Cayrol says. “There is space for a one-stop-shop for VR.”

Full Steam Ahead

Still confusing to me, though, is where this content actually goes. Atlas V is publishing on Steam and Quest but, as I’ve said, these are primarily gaming platforms that don’t give much thought to the industry. Cayrol is the first to agree that sales for the company’s movies on Steam are not as high as many games but he does point to one encouraging sign. “Every month, it’s [the number of sales] is better than the month before,” he says.

“It’s growing. It’s like the opposite of the cinema business. The reality of it is, if it’s not doing great one week, they remove a film from the screen. And for VR, it’s really fun because every month I get 10 people more than the month before on every project. So then we can try to put a business model on that.”

Release dates, Cayrol suggests, aren’t as crucial to VR movies as they are games. As for the platforms themselves, Cayrol isn’t so sure that VR needs a third store competing for eyeballs. Instead, he reasons Steam and Facebook could provide more space for movies. “I think [the industry] will be driven by gamers, but then, I’m a gamer. And gamers? We watch movies. We watch series, we are not only gamers and I think gamers will watch narrative content. What I think is needed is more space for them in Steam and Oculus.”

The other piece of this puzzle, though, is pricing. It’s a sticky point for VR as a whole, with the value of many games constantly called into question. Price tags are weighed up against hours of playtime – a metric that isn’t really fair to judge a film by. So what do you do? Compete with DVD and cinema ticket prices? Or try something different?

“At the moment I need to think about the audience,” Cayrol says. “If I give them a 35 minute piece, I don’t want the audience to be disappointed, so I cannot put it at $14.99. I also can’t put it at $1.99 because it won’t be a gesture of value for my director. It costs money and I need to pay my artists.”

The result varies from piece to piece, then. Ayahuasca, a film in which viewers are subjected to visions, has a higher price than, say, Gloomy Eyes because it has a strong audience and plenty of replayability.

The Future Of Showbusiness

It’s encouraging to find such optimism in Cayrol’s outlook, then. But, again, it’s not all going to change overnight. In fact, Cayrol anticipates things staying pretty much as they are now for a little while longer.

The future is hopeful, though. Battlescar is finally coming to home-based headsets later this year, and Atlas V is busy at work on some exciting new projects. One is called 38 Minutes, telling the story of the 2018 false missile alert in Hawaii in which an erroneous phone alert warned people of an incoming ballistic missile. For 38 minutes, the island’s population thought death could be seconds away. Cayrol explains that the team got audio testimonies about the experience that will form the basis of the piece, and sounds very excited about it. It’s set to run the 2021 festival circuit, whatever that may look like.

With the COVID-19 pandemic hitting pause on location-based VR for the foreseeable future, I’m more curious than ever to see how and where a true home for VR movies turns up. Personally, coming from a gaming background, I routinely find VR movies to be fascinating and full of potential, and I’m desperate for the audience to grow and start nurturing this side a little more. I take heart from Cayrol’s positive outlook for the future of the scene, even if I find myself a more than a little impatient to get there.

Where To Download Atlas V Movies:

- Gloomy Eyes – Quest Steam

- The Dawn of Art – Steam

- Ayahuasca – Steam

- Spheres – Rift

- Vestige – Steam

- Battlescar – Steam (Coming Soon)