The conventional wisdom for VR content says: tread carefully. Don’t go too far. Ease your audience into this new technology with fun, thrilling, exciting things, or maybe a documentary with some sort of edifying lesson. In a new medium which has only just begun to penetrate the consumer market, should content producers treat their VR audiences with such precaution? Or is it okay to shock them, scare them, and make them cry?

Do you always need a happy ending? How far is too far, and should the industry set limits?

Pushing The Limit

Serious and dark themes have always been popular in theater, film, television, and literature. Charlie Brooker’s critically acclaimed show Black Mirror, recently having launched its third season on Netflix, presents a twisted dystopian view of society and the negative effects of technology. The endings certainly are not always happy. Audiences flock to horror, tragedy, and melodrama in every other medium, so why should they not do so in VR?

VR is different from every other medium that has come before it, and herein lies the problem. With VR, the viewer is ‘in the room’ when the bad things are happening—as a complicit observer, as a participant, or even as a victim. The realness and closeness of it all can be intense and overwhelming.

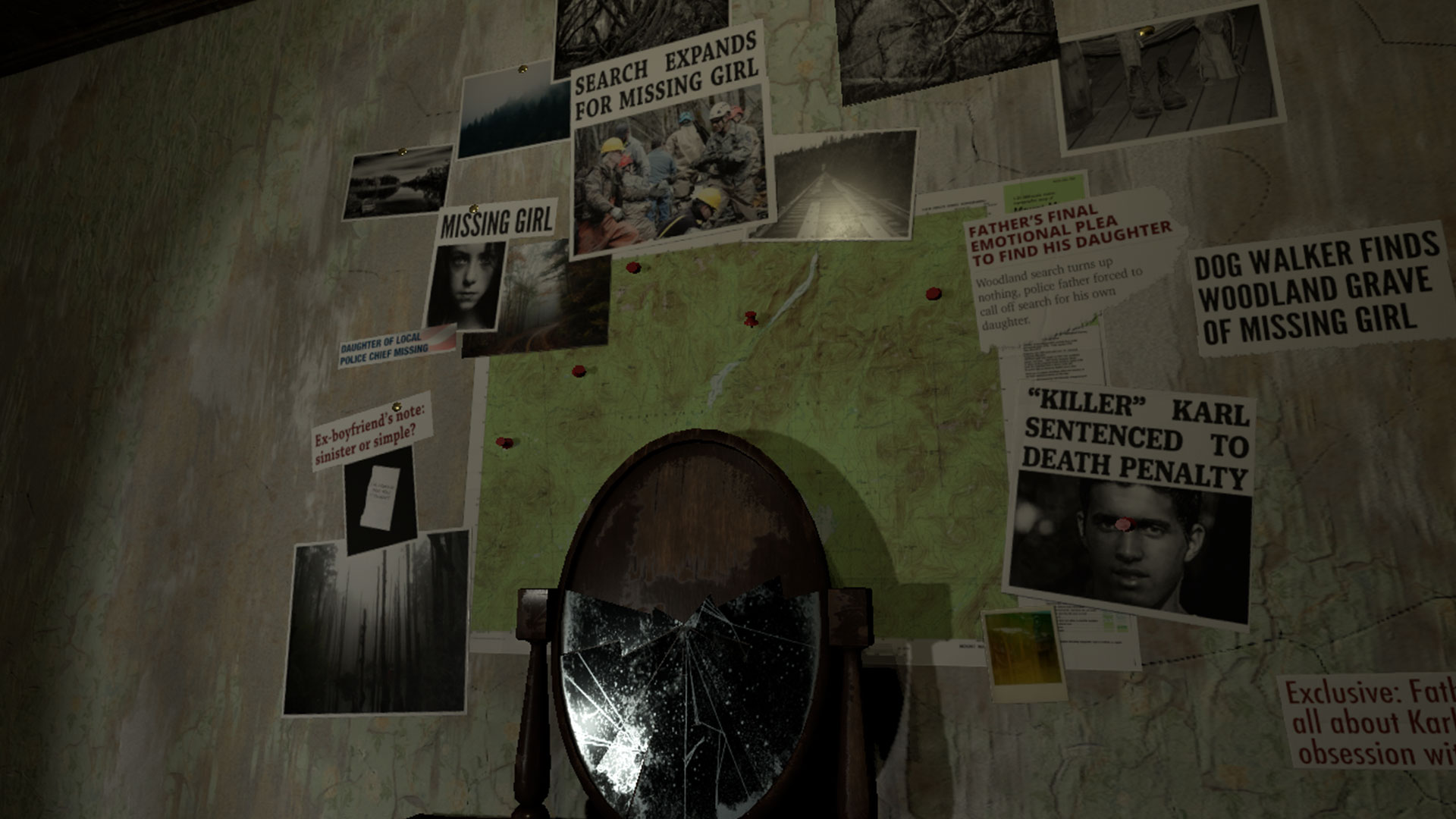

Several studios have taken the plunge into VR horror films and games with pieces such as Sisters by Otherworld Interactive, Catatonic by Guy Shelmerdine for Within, and A Chair in a Room by Wolf & Wood. These push boundaries and make users uncomfortable—and have been well received for exactly these reasons.

But what about more realistic stories? Are viewers ready to see raw and honest depictions of violence, illness, heartbreak and grief? Two notable examples of such VR content, both out of the UK, are In My Shoes by Jane Gauntlett, and Ctrl by London-based studio Breaking Fourth.

In My Shoes takes the subject of epilepsy and makes it intimately and uncomfortably personal. Combining elements of documentary filmmaking and immersive theater, this piece places you directly into the shoes (or rather chair) of Jane Gauntlett, moments before she suffers a seizure. The viewer merges with Jane sharing an evening with friends – hearing her thoughts, looking down to see her hands on the table – to such a realistic extent that the disorienting after-effects of the seizure feel disturbingly real.

Breaking Fourth’s Ctrl tackles the issue of domestic violence in the context of a fictional narrative. The viewer in this case takes on the role of an observer, unable to act as a horrifying scenario unfolds just out of reach. Viewers of this drama are placed in a tough position – observing a distressed family, and hearing, but never quite seeing, the clear signs of domestic abuse in the home.

VR pieces such as these can be polarizing with an audience, with viewers often unsure of their emotions afterwards. Audience members can be found visibly shaken or dazed by these pieces, disturbed by the realism. Despite the difficult subject matter, challenging and dark VR content can serve to inform and educate about real-world problems, and can arguably do so more effectively than other media can thanks to its immersive nature. Thought-provoking, challenging content can also be cathartic for an audience in a way that hearkens back to ancient Greek and Shakespearean tragedy.

However, there are risks associated with pushing such boundaries. Some viewers might be angry or upset by what they have seen, or might not understand the point of being made to feel strong negative emotions, or might question the lack of a happy ending. Only later, after further reflection and education, might they realize that the purpose of the piece is in fact to specifically provoke a strong emotional reaction—one that stays with the viewer. In the case of Ctrl, the helplessness of the viewer mirrors the real world helplessness that many victims of abusive relationships feel.

Fundamentally, this sort of emotionally harrowing content taps into the viewer’s fight or flight instinct. While immersed in a VR experience, the viewer is transported to a different reality, and much as in a dream, the viewer might feel they cannot leave until it ends. When confronted with unpleasant issues on a traditional 2-D screen, the natural reaction of a viewer is to turn away, change the channel or just think about or look at something else.

However, in virtual reality, this is not possible, or it is much more difficult. The viewer is placed within the experience, and whichever way they turn or wherever they look, they are still in the virtual environment. The sound surrounds them and their attention is wholly captive to the story. When viewers cannot flee or divert their attention away from an upsetting situation, they are left with only one option: to confront it, to fight it. This type of reaction can lead to unpredictable emotions. Some viewers are left in tears as they process the harshness of the situation. Some are angry that they were made to feel that way. Others are simply stoic and introspective.

One way to deal with these reactions is by providing person-to-person support following a public screening of the piece. In July of this year, Breaking Fourth spent two weeks screening Ctrl in a theater space using multiple Samsung Gear VR headsets. After each showing, the production team informed the audience that there were domestic violence support leaflets and flyers at the door, and also that staff members were on hand to talk to anyone who wanted to about what they had just seen.

Becoming More Than A Novelty

At Oculus Connect 3 in October, John Carmack remarked that VR is ‘coasting on novelty’ and that, for the platform to be successful, content creators need to “start judging [them]selves…not on a curve, but in an absolute sense. Can you do something in VR that has the same value, or more value, than what these other [non-VR] things have done?” In this nascent stage of consumer VR, much of the content is indeed of the “wow-factor” type, where wonder and 360-panoramas take priority, but complex stories and emotions are secondary, or are not present at all. This is gradually starting to change, with pieces such as Ctrl, In My Shoes and the immersive horror titles discussed, and with a further pipeline of new scripted dramas set to be released from these producers and others. Ctrl was screened at Oculus Connect 3 and, as expected, reactions were mixed, but always strong.

As VR reaches a more and more mainstream audience, content must evolve and mature to continue holding the attention of an average viewer, and to justify the price paid for hardware and content. VR as a medium will need to become as diverse, exciting and original as standard filmmaking is today. Consumers have always shown a propensity towards dark and difficult content in every other medium out there, and they should eventually embrace it in VR as well. However, the unique aspects of VR as a medium — the immersiveness, the inescapability, the hyperrealism and the forced attention present challenges to the industry — make VR a unique beast to deal with. VR producers should not be afraid to take risks and provoke strong emotions in viewers, but the nature of such content needs to be messaged properly in advance, and, if possible, supplemented with post-viewing support.

Once the VR industry has taken the leap into more serious and complex storytelling, VR has the potential to become the premier medium for emotionally-charged narratives that grab and affect viewers in a way no other medium can.

Bertie Millis is Co-Founder and Managing Director of the award-winning Virtual Umbrella. He is also London’s Community Director for Kaleidoscope VR and works to promote UK VR creativity to the world. Follow him on Twitter: @Bertaroo.

Disclaimer: Virtual Umbrella provide marketing consultancy services to Breaking Fourth.