As mainstream VR/AR input continues to evolve – from the early days of gaze-only input to controllers and fully articulated hand tracking – so too are the virtual user interfaces with which we interact. We’re moving beyond flat user interfaces (UIs) from 2D screens toward a future filled with spatial interface paradigms that take advantage of depth and volume.

At Leap Motion, our team is constantly pushing the boundaries of our interactive VR toolkit. Recently, we created a VR sculpture prototype to explore its performance and usability. Along the way, we experimented with how spatial UIs could be used to control aspects of that sculpture – or any piece of complex content – by creating a playful set of physical-like user interfaces.

In the spirit of open exploration, here’s a journey through our latest round of rapid prototyping and design. Along the way, we’ll see how dynamic feedback can elevate a humble button press into a compelling and intuitive virtual interaction.

A Living Sculpture

We built the Leap Motion Interaction Engine to give developers the power to define the physical laws of the virtual universe. It unlocks virtual objects and physically inspired interfaces that you can pick up, throw, nudge, swat, smoosh, or poke. The concept of a VR sculpture was a great way to put the Interaction Engine to the test. (For a deep dive into this part of the project, check out our blog.)

[gfycat data_id=”BouncyAcidicHammerheadshark”]

Once we built the sculpture, it was time to take the interactions to the next level.

From Flat Screens to VR Interfaces

When someone first puts on a hand-tracking-enabled VR headset, it often seems they’re rediscovering how to use their own hands. In a sense, they are. When we bring our hands into a virtual space, we also bring a lifetime’s worth of physical biases with us. Compelling spatial interfaces complement and build upon these expectations.

For this exploration, we wanted to focus on physicality, playfulness, and conveying the distance between hands and UI elements through dynamic feedback.

A conceptual mood board featuring interfaces both simple and complex, with a focus on physicality and play. We also explored ideas around form, affordances, and use of color accents.

A conceptual mood board featuring interfaces both simple and complex, with a focus on physicality and play. We also explored ideas around form, affordances, and use of color accents.

Since it was designed to run on mobile VR headsets, we knew that it might be experienced with only 3-degree-of-freedom head tracking. This meant the user would be seated and UIs needed to be within arm’s reach. With that in mind, we used curved spaces, which allow entire user interfaces to be warped into ergonomic curves.

[gfycat data_id=”PlaintiveClumsyBubblefish”]

Once we defined the layout, it was time to design the user interfaces themselves.

Building a Button

Since the iPhone introduced multi-touch input in 2007, we’ve seen 2D touchscreen interaction design evolve into a responsive, motion-filled language. Modern apps respond to any input with visual, audio, and sometimes even subtle haptic feedback. Taps and swipes are met with animated ripples and dynamic element resizing.

In VR, every interactive object should respond to any casual movement. Users don’t always know what to expect, and dynamic feedback helps to build a mental model of how the virtual world works, and what each action achieves. Without dynamic feedback, an interaction can feel unsatisfying and weird.

Beginning with the most fundamental of UI elements – a button – we asked what this sort of reactiveness might look like in VR with hands. While touchscreen button interactions are binary (contact vs. non-contact), pushing a button in 3D involves six distinct stages:

- Approach. Your finger is near the button, which may start to glow or otherwise reflect proximity.

- Contact. Your finger touches the button, which responds to the touch.

- Depression. Your finger starts to push the button.

- Engagement. Success! The button may change its visual state and/or make a sound.

- Ending contact. Your finger leaves the button.

- Recession. Your finger moves away.

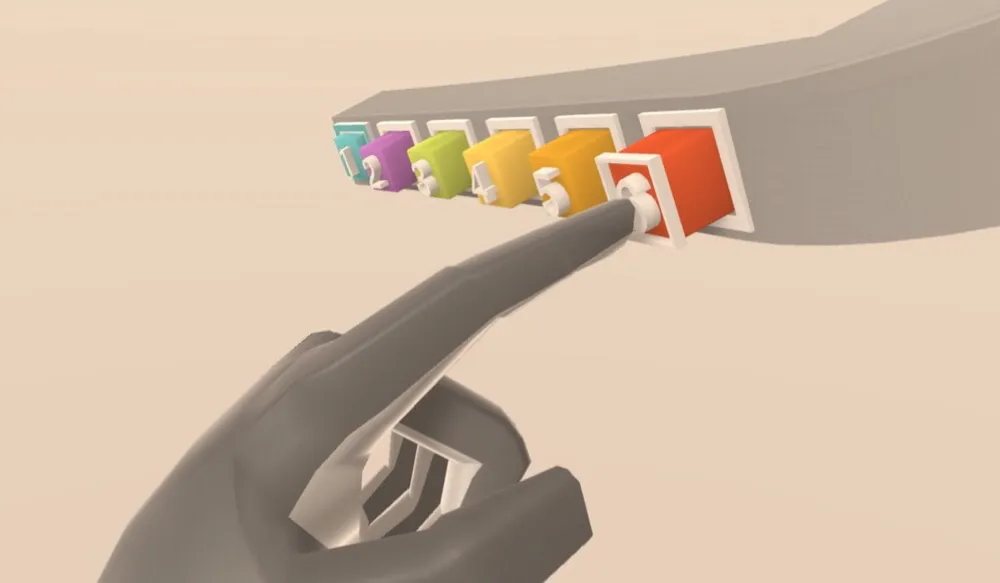

When your hand approaches a button in this prototype, a white ring rises up from its base to meet the contact surface. As your finger gets closer, the ring gets closer, until contact is made and the ring reaches the top of the button.

Depressing the button until it engages changes the color of the button frame. Along with an audio click, this confirms the successful completion of the interaction. When contact between finger and button ends, a second slightly higher-pitched click marks the end of the interaction. The white ring recedes as the user moves their hand away.

[gfycat data_id=”UniformLinedAnemone”]

[gfycat data_id=”ArtisticRichDaddylonglegs”]

These are actually toggles (the stubborn cousin of the button). They activate all of our sculpture’s presets.

A similar approach with an expanding white inner ring was used on the sliders.

[gfycat data_id=”UnfoldedIllfatedBison”]

[gfycat data_id=”FarflungGiddyDragon”]

Before settling on rising (or expanding) ring feedback, we also experimented with having the button morph as a finger approached. The idea was to make the button convex at rest, affording the action of being pushed. As your finger approached, it would morph into a concave shape, metaphorically providing a key to the button’s lock.

Inspired in part by the finger-key from The Fifth Element.

[gfycat data_id=”UntriedAdmiredIslandcanary”]

[gfycat data_id=”FirstAshamedAmazonparrot”]

This style took full advantage of the 3D nature of the UI components and felt very interesting. However, it ultimately didn’t communicate how close the finger was as effectively as the rising ring approach. At some point we would love to delve deeper into this concept, perhaps by having your hand mesh also morph – turning your fingertip into a key shape.

Physical VR User Interfaces

Beyond adding spatial UI feedback for buttons and sliders, we were also curious to see whether a common mechanical input from the physical world would be compelling in VR. Physical trackballs are highly tactile with a wide spectrum of interaction levels. They can be manipulated with a fingertip and dialed in with slow precision or can be spun with force like a Kugel Fountain. A trackball seemed like a prime candidate for virtual recreation.

[gfycat data_id=”DaringOrderlyAnaconda”]

[gfycat data_id=”CourteousHiddenFishingcat”]

This spatial user interface playset is just a glimpse of the possibilities afforded by the Interaction Engine’s physics-based foundation. What kinds of 3D UIs would you like to see, touch, and create with these tools?

Mood board image credits: Iron Man 2, Endeavor Shuttle Cockpit, Fisher Price Vintage, Matrix Reloaded, Wirtgen Milling Machine, Fisher Price Laugh and Learn, Grooves by Szoraidez, Google Material Design Palette, sketches by Martin. This is a guest post not produced by the UploadVR staff. No compensation was exchanged for the creation of this content.”