The recent announcement of Vrse changing its name to Within is representative of an important shift in the way certain artists are thinking about VR. Chris Milk, one of the leading creators in the VR space is moving away from thinking about VR as a medium in which the author tells a story, and toward thinking about it as a medium in which viewers can, for the first time, step directly into the world of the creator.

Storytelling has always been conducted by authors peering into their own imagined worlds and documenting what they see for their audience in the form of a linear narrative. VR is different and holds the potential for a deeper way of communicating stories because the authors don’t need to do the telling, instead they are actually publishing their fictional worlds for viewers to peer into themselves and experience from Within.

In previous mediums, stories are told and the “telling” relies on the use of explicit means to document what an author sees in their imagined worlds. The story, which takes the form of a linear narrative, is bound by the limitations of language (symbolic communication) which make the telling of it inherently explicit. This works incredibly well with books, and film in which creators have many explicit tools they can use to “tell” the story. Novels guide you word by word, film strictly controls your attention through the use of frame. Even storytelling within games generally involves taking a step back from its interactive elements and inserting a cut scene or forcing you to follow pre-built narrative arcs (eg. Fallout 4). Accordingly, traditional storytelling has involved an explicit plan and structure and that works well for books, film, and most other previous mediums.

Milk:

Until now, storytelling mediums have allowed us to share approximations of human experience in external frames — forms that take up space in the physical world: books, letters, theater stages, movie screens, TVs, smartphones, tablets. While the stories we tell using these forms help bring us closer than ever to the lived experiences of others, they don’t give us the ability to live within those experiences firsthand.

Indeed the medium and artistic material of VR is highly spatial. To experience something in VR is to be immersed within a different space. The illusion of presence is only possible if our brain thinks we’re actually there. We don’t have to be told, rather we feel viscerally whether we are present or not. Presence is a bodily sense or feeling, and feelings are how we experience what is implicit. The power of VR lies in its ability to transfer implicit knowledge and narratives. Empathy, a much talked about quality of VR experiences, is just that, a form of implicit understanding. With VR, you’re creating spaces in which powerful implicit narratives can occur. You’re not telling a story, you’re building a world in which you create the potential for stories to emerge and manifest.

Milk:

VR opens the door to what Jaron Lanier (who coined the term virtual reality in the 1980s) calls “post-symbolic communication”: No longer are we limited to communicating via sequences of symbols represented by audible vibrations of our vocal chords, or produced by our fingers pressing on a series of keys or, more recently, a flat piece of glass. Instead, you experience my dream directly, without having to interpret long strings of verbal or written symbols.

So what does that mean for the content creator?

Resist the urge to tell stories, instead, build a storyscape (a great term used by TFF for their immersive and interactive showcase) in which the user has the potential to engage in emergent narrative structures (for examples, look at what James George and Alexander Porter are developing with their new project called Blackout).

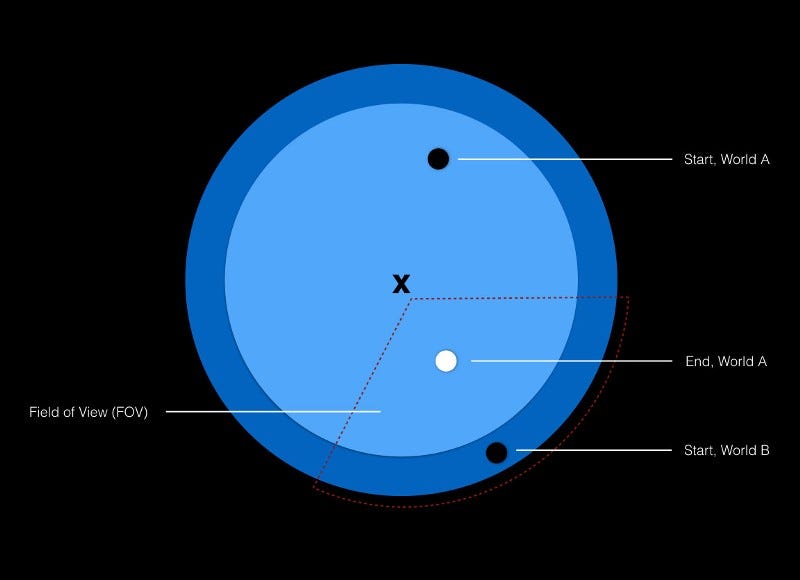

Jessica Brillhart echoes this sentiment effectively by using concentric circles and dots to sketch out possible narrative potentials of the storyscapes which she is creating (watch this video for some of the best practical advice on VR storytelling out there).

When asked to offer practical advice for VR creators, Chris Milk had the following to say:

Every rule we’ve discovered and employed in traditional filmmaking has an entirely new effect in VR. It’s very exciting. All the tools I’ve learned to love as a filmmaker now operate differently. Someone looking into the camera through a rectangle feels leaps and bounds different than someone physically staring back into your eyes in VR. Camera movement is a major challenge. We’ve learned early on that the camera needs to be treated like a person itself. Accelerating movement of the camera, and shifting the horizon line can lead to nausea. But it also provides us an opportunity. In Evolution of Verse, I use acceleration in a specific shot where you’re being lifted off the ground, but did so delicately. The result is that you feel a physical sensation of actually moving off the ground when you’re in this shot, even though your physical body is standing still. We modulated the effect to give you this sensation without allowing for nausea. It’s a great example of how a small device can have an impact on the audience that we’ve never been able to tap into before in other mediums.

Milk’s advice makes clear that the language of VR is an expressive one. The techniques and devices that he refers to have physiological effects not theoretical or propositional ones. The viewer isn’t told they’re being lifted off the ground, they instead “feel a physical sensation of moving off the ground”. He also said that we should think of the camera as a person, which Jessica Brillhart would agree with, but I would instead suggest that there is no longer a camera at all. The camera represents a view or window, looking into a story universe but in VR there is no window, the viewer is not viewing, they are experiencing and existing within the imagined world of the creator.

Creating these worlds is not a new endeavor or challenge for storytellers. All good stories emerge from rich worlds that that were imagined by their creator. I doubt that Dostoyevsky was able to tell his stories if he wasn’t intimately familiar with the world from which they came.

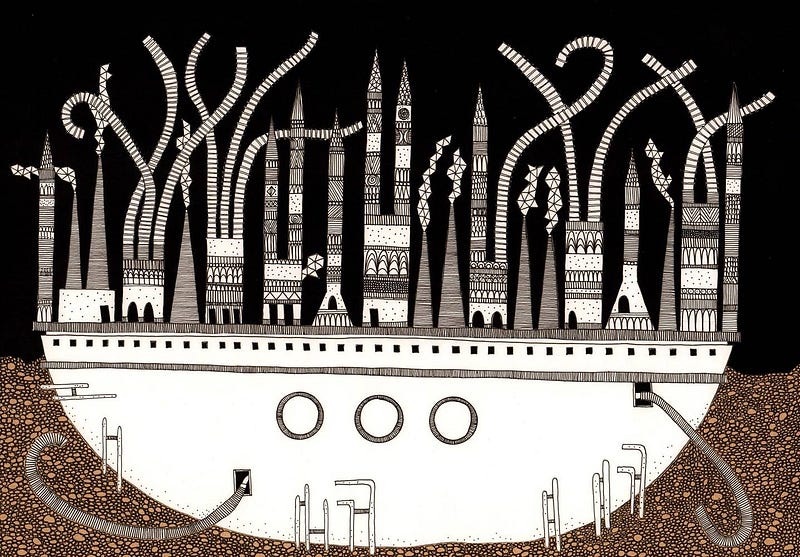

Or, take for example the elaborate poleis, necropoleis, and metropoleis brought to life in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities.

Skilled authors build the world in their mind first, then they observe and let the best stories emerge almost on their own. This is the part of the creative process that VR can tap into.

Instead of being told stories in VR, the viewer is in part also the storyteller, but for the first time authors can share the vast world in which they create from which their powerful narratives emerge. Usually, the story that is told is just a small part of the work and effort that the author put in to create an organic, living, fictional world.

VR affords the opportunity to bridge that distance. Reducing the need for explicit storytelling, and allowing us to experience and feel a story through deeply implicit means, by stepping directly into the imagined world of the creator. Art has always been limited by the frame, it’s vital information sometimes lost in translation when compressed into symbolic formats, with VR perhaps that won’t be the case anymore.

Milk:

The stories of tomorrow will be fully immersive. The medium, the place where those stories will unfold, exists within our consciousness. We’ll find ourselves having passed through our long-held, precious frames to live within those stories. And we’ll carry the memory of those stories not as content that we once consumed, but as times and spaces we existed within.

A version of this article was also posted to Medium. Feature image source: “Dreams of Dali” The Dali Museum / Goodby, Silverstein & Partners.