The courtrooms of the future, from the jury to the prosecution process, may look different thanks to the rise of virtual reality.

Several experts contacted for this article are working on ways to innovate the legal profession to usher in VR tools to make the trial process, and the law student experience, more immersive and engaging.

“VR will definitely be the future of litigation in both court and jury trials,” says Mitch Jackson, an Orange County lawyer who often discusses tech trends in law at conferences and with media. “For one, it can create a more thorough environment for jurors to look at facts and to help them come to their final decision.”

Two major projects are aiming to transport jurors to crime scenes. At Staffordshire University in the U.K., a research group created a system that places jurors into the middle of a crime scene while also allowing an attorney to guide viewers through the scene and its evidence.

“Doing that in a way that is far easier for juries to understand and appreciate — which can only be good for everybody, for prosecution and defense,” Simon Tweats, the head of justice services at Staffordshire Police, told reporters.

Also, researchers at Durham University are developing a robot system inspired by NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover that could capture immersive video footage of crime scenes. Lead researcher Mehzeb Chowdhury explains the system’s mission: “Scene degradation occurs from the moment the crime begins and continues until the last officer turns off the lights and leaves the scene. Actions of suspects, witnesses, the first responding officers, EMS, the environment, and certainly those of the crime scene processor will result in the disturbance and alteration of the scene. Given this understanding of the inevitability of scene alteration, the basic goal of the MABMAT is to enter a crime scene, capture it in 360 degrees and then produce unedited, out-of- the-box footage and stills that can be presented in court.”

He adds the MABMAT system requires no 3D-rendering, texture scanning, or gaming engine. “It runs on any computer or smartphone, capable of playing video. All is needed is an app, or computer program,” says Chowdhury.

The rover is still in the prototyping stage, but demonstrations have been conducted for several police forces. The unit costs $500 US.

What benefits would a project like MAMBAT offer legal professionals? “Defense lawyers may be able to explore a crime scene in great detail, and formulate better defences,” says Chowdhury, “and the prosecution could make sense of the evidence and contextualize a crime. and detectives or investigators could actually revisit scenes to ascertain whether they actually missed anything the first time, or to add perspective to already-collected evidence.”

Plus, imagine if juries could view a crime scene and make up their own minds about what may have happened, rather than being overwhelmed by conflicting prosecution, and defense 3D scene recreations.

Multiple efforts to use VR in court

VR recreation for jurors is an idea that has also come to Canada, although it has yet to come to fruition. Anita Krajnc is an animal rights activist whose trial is currently underway in Toronto: she was arrested for meddling with a tractor-trailer that was transporting pigs to the Fearmans Prok processing site in Ontario. Krajnc was attempting to give water to the animals at a traffic light by sliding a bottle of water through gaps in the enclosure. She now faces a maximum sentence of six months in jail and a $5,000 fine.

In August, her lawyer James Silver made it clear he wanted to bring VR headsets into the courtroom to help demonstrate that, instead of causing harm, she was in fact helping the animals. To do this, the headsets would show footage from inside a factory farm and slaughterhouse, giving jurors a view of the conditions that pigs and other animals face by putting them in the experience.

Jackson says it’s practically a no-brainer to allow VR headsets into the courtoom for jurors. The reality of jury trials is the lengthy wait times, he notes. Often, a deluge of people will be summoned to the courthouse on Monday morning but there aren’t enough rooms for trials to begin so jurors sit around for days and then may be dismissed.

“With virtual court rooms we won’t have that problem,” says Jackson. “We’d have trials take place without a physical location required. Attorneys can be in offices or down in the beach with toes in the sand. Jurors can truly represent a variety of demographics, and can be from any location [by wearing the VR headset from their own home].”

A couple years ago, Lars Ebert, a researcher at the Institute of Forensic Medicine Zurich, published a video examining the use of the Oculus Rift to explore 3D computer reconstructions of events and crime scenes discussed at trials. Why is he bullish on VR in the courtroom?

“The judges and state attorneys get a much better idea about the incident scene, which is similar to them being there,” he says. “They are able to investigate the scenes for themselves under guidance by an expert, they can look at the scene from different angles and positions – which is something they cannot do on a 2D rendering.”

Ebert believes that in some instances, VR can save costs. “While at the moment, judges, police state attorneys and everyone else involved in such a case visits the scene, in the future this could be done virtually – maybe even without leaving the office. This would reduce overhead from organizing such an event and traveling to the scene.”

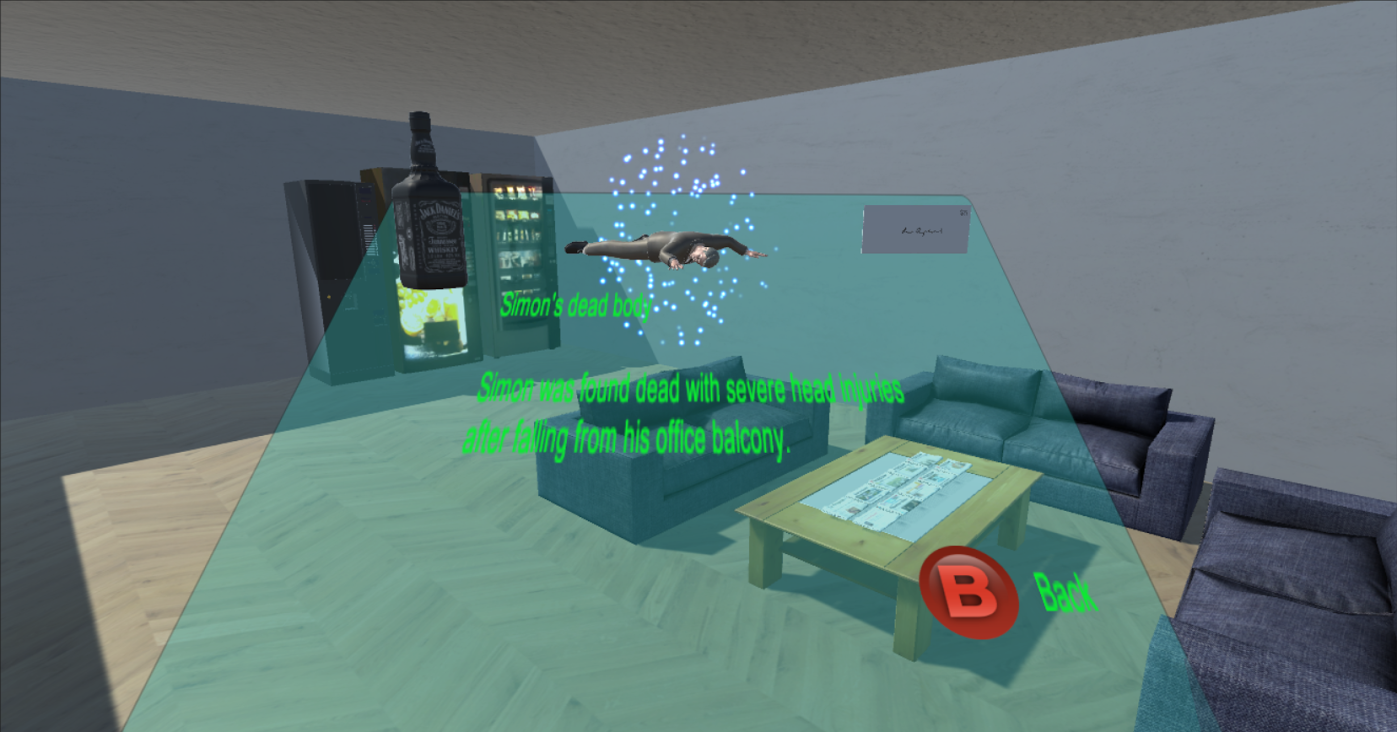

Ebert tells me about a scene his team reconstructed for VR. In this case, the police tried to arrest a suspected drug dealer in an Internet café but since they didn’t secure that suspect properly, he could get up, draw a gun and fire seven times, hitting an officer once in the arm. His colleagues also performed a laser scan of the scene. “The question was how close the gunshots were to killing someone. So my colleagues created a reconstruction for each bullet fired based on the available data. What you see on this image [below] is the gunshot that hit the officer in his arm as visualized in VR.”

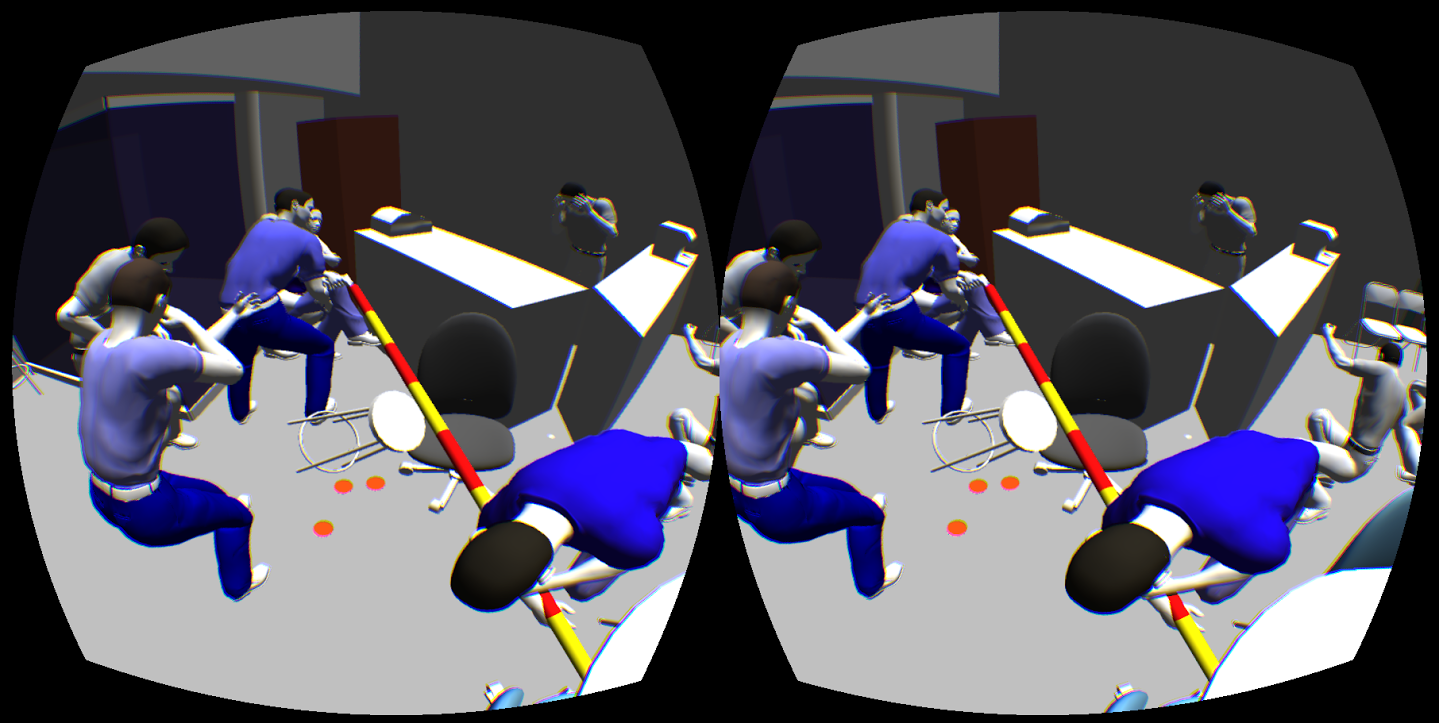

VR’s potential is also being explored at various law schools. At the UK’s University of Westminster, law students use VR headsets and a recreated crime scene to analyze pieces of evidence and even interact with participants. The case study involves two brothers who run into financial problems while shooting a film — leading to the death of one of the siblings.

Markos Mentzelopoulos, a senior lecturer in the university’s computer science department who helped create the scenario for law students, says this technology doesn’t replace the textbook but complements it. “We want to ensure that when these students look at the crime scene, they don’t overlook anything. We want them to be open-minded.”

Using an Xbox controller, students can tour the VR-created scene and press buttons to initiate conversations with potential witnesses, or talk to detectives, or highlight certain items in the room. The project is currently underway with the law students and Mentzelopoulos will request feedback from them on what worked, what didn’t.

All these examples give the impression VR’s entry into the legal profession would be an ideal way to court innovation at its finest. Not so fast, says Jackson. “The legal profession is hesitant to adopt new technology.”

Questions about fairness And accuracy

Carrie Leonetti, an associate professor at the University of Oregon’s School of Law, identifies three main challenges for VR’s chances of impacting lawyers and jurors: “Expense, in particular in the context of inequality of arms between parties and the powerful effect that these tools could have on jurors; judicial resistance and fear of anything new; and questions about whether VR scenes are accurate representations of what they purport to depict and how courts can ascertain that with any reliability.”

Leonetti goes on to say she would have profound concerns with a criminal trial in which “the prosecution could create an immersive VR reconstruction of its version of events, with its powerful potential persuasive impact, and the defendant’s public defender could not afford to fight fire with fire, if you will. You see that imbalance already with crime-scene reconstruction videos, arson reconstruction models, forensic computing resources.”

What could also be a struggle is how jurors wrestle with a new technology that they might not find comfortable. Motion sickness and eyesight issues could play a role in how seamless the VR experience will be for jurors.

That being said, it is evident that VR will seek to encourage an engaged process during trials, whether in law school to immerse students in real-life cases or in the jury booth, where finding a decision may be made smoother with a platform already used by professionals around the world.