Cyan Worlds’ new puzzle-adventure game Obduction, if our review and the rest of the internet’s reviews are any indication, will surely enchant VR gamers in the same way the company’s original, groundbreaking title, Myst did computer gamers back in 1993. That’s appropriate, because building it posed many of the same technical challenges.

In the same way that Obduction will help to pioneer photorealistic VR gaming, Myst broke new ground for computers. The game used vibrant colors for example, which was still a bit of a novelty. And it used the CD-ROM drive, which was still new enough that running Myst was a selling point for many computer owners to get a CD drive to begin with.

But developing for a bleeding-edge platform, whether it’s VR headsets like the Oculus Rift, or a simple 1X-speed CD, comes with drawbacks. Miller said these most recent challenges came with a heaping serving of déjà vu.

The high-level summary of those challenges were, “Size-related, streamlining performance, making it look good — good enough — but on the lowest end machine we could,” Miller said. “For Myst, it was the same story. I’d wager a bet that people see our little slideshow images on Myst [now] and think, we didn’t fight the same battles. But we did, it was exactly the same battles.”

For the original game, he struggled with the limitations of the medium: because CD-ROMs were designed with a spiral track for audio, developers had to figure out how to physically place files close to each other on the disc, so that moving from one scene to another or changing from one soundtrack theme to another didn’t cause a hitch in the action.

For VR, Miller was developing for a platform that didn’t yet exist. Cyan developers had the early development kits, he said, but exactly what state the tech and hardware were going to be in by the time they released was a bit of a myst-ery in and of itself – and has contributed to the game’s delayed release in VR.

“All of this we’re planning is before we even had a VR headset. You’re not just shooting at a moving target, you’re shooting at a target that hasn’t come over the horizon yet,” he said. “All of that is trying to figure out what is going to fit and what our minimums are going to be and what the frame rates are going to be. All of this has to come to perfect union at exactly the right time. You do get some hiccups. I’m amazed at how close we called it.”

The company is working on frame rates in particular right now, he said, dealing with a couple of locations they’re not 100 percent happy with.

“The desktop [version] is a little more forgiving with frame rate than VR,” he noted wryly.

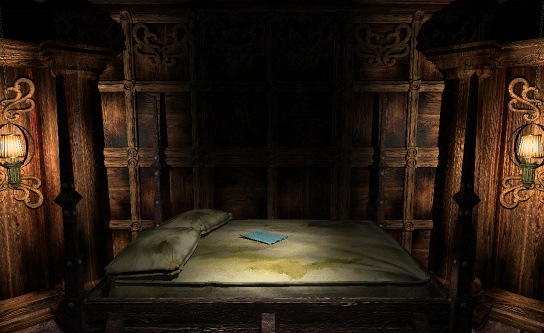

In the original Myst, Miller and his brother Robyn used a custom-modded version of Hypercard, a card-based slideshow/development program built into early Macs, to help gamers move through beautiful environments, searching for clues to solve puzzles. Hypercard didn’t come with the ability to show color, so they had to program that in.

“For motion in the world, we have this awesome legacy that everybody who does VR realizes is perfect for what we do: moving from one spot to another spot, jumping from one place to another place,” Miler said. “It was beautiful in this spot, and you clicked, and you went to the next beautiful spot. It’s so bizarre how VR feels exactly the same way.”

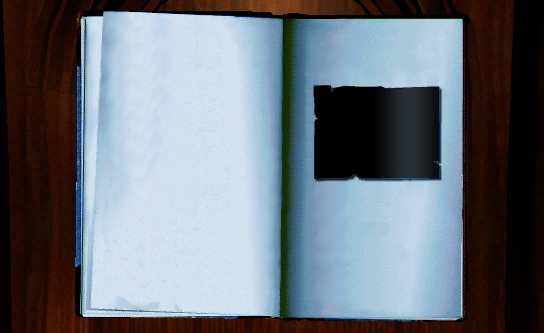

A (then) brand-new software program called QuickTime allowed them to show movies in Myst, but the files were too large to easily include in the game, so they came up with the idea of putting them in books to constrain the window size.

Those size-and-tech constraints have popped up again in the new world of VR.

“We’re trying to squeeze as much performance out of these very detailed worlds as we can,” Miller said. “VR puts another clamp on that. I’ve got two eyes I’ve got to feed data to, and I’ve got to do it at a frame rate that doesn’t make people irritated.

“We don’t want to do it at the expense of our beautiful world. We’re known for making things photorealistic. We don’t want to say, ‘We’re going to make this look like a cartoon.’ People wouldn’t be satisfied with that.”

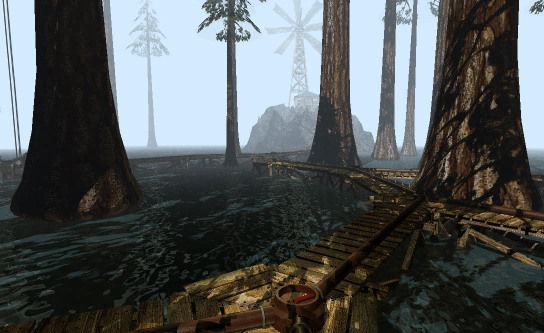

In Obduction, Miller ended up using the same hop-to-the-next-location technique he used in Myst, and many developers use in VR now, to solve another problem: motion sickness. Smooth motion, in addition to being a challenge to render for photorealistic environments, also makes new VR gamers uncomfortable.

“The first time I went into the game, it actually slowed me down,” he said. “I’m in a spot and it’s so beautiful. I can imagine people playing Myst that way. I wanted to look all around me. It’s serendipitous that we’re in this place again, with the same kind of navigation that we did 20 years ago for Myst.”

Live action still presents the same old problems, he said, but for new reasons: while the actors are filmed in 3D, the current state of VR doesn’t work well if gamers try to move around live action in the scene – especially on Cyan’s budget.

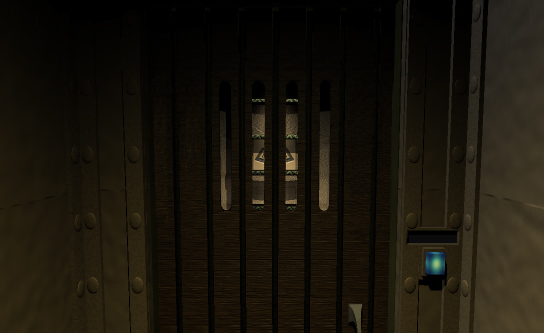

“We designed it so that the person who’s displayed has a reason that you can’t go around,” he said, explaining that you’ll see characters through doors or windows, on displays and imagers. “All of those things are part of the design that lets you see a character and lets it feel real – we recorded it in 3D – but it makes sense that you can’t go around it. It’s the same thing when people see Myst and see the brothers in a little postage stamp in a book.”

In Myst, that tech limitation meant that elevators had little tiny windows, so the movies that played through them could be equally tiny. In Obduction the elevators are open, but still have a hefty framework around them – this time, to keep people from feeling sick due to the motion.

“Elevators can be an issue,” he said. “We’ve learned from other people’s research and some experimenting on our own that if you build something around people, it feels like a cockpit and you can get away with a little bit of motion and not make people sick.”

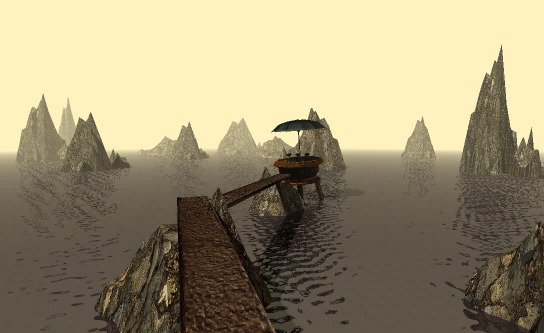

Vertical movement posed a particular challenge in Obduction, where elevators and ramps take the place of the ladders and small jumps you might have seen in earlier Myst titles.

“We were early enough we wanted to be safe rather than push people,” Miller said. As a result, all short jumps were tossed. “There’s a couple spots in the game, where there’s a short cliff that looks like you should fall off of it. Most of them we put a little blocker there or a little ramp so you don’t think twice about it. But there may be one or two where you might think, I should be able to drop off this.”

Miller said as a developer and a gamer, creating Obduction has brought back some terrific memories from the original Myst.

“It’s a really cool feeling, to put people in front of Obduction and watch them play in VR, because it harkens back so much to putting people in front of Myst and watching them play in front of this color monitor,” he said. “I have this sense of déjà vu, and sit there with this little smile on my face. I just love that.”

He said VR represents the first real leap forward in immersive gameplay for titles like his since Myst was released. It came out at roughly the same time as DOOM, so 3D gameplay was already there. They had color, and while resolution and numbers of colors have improved (Myst had a whopping 256), at its heart, gaming has been the same. Not any more, he said.

“We’ve had the same kind of delivery mechanism for a long time. But it’s still a small little window into a larger world. VR puts you there. It really does,” he said. “It really feels like a special time to be solving these problems and get this stuff out. I feel like we’re privileged.”

The standard non-VR version of Obduction is now available for download on Steam, GOG, and the Humble Store. Our review is based on the VR version that will be available through Oculus Home. Buying the standard non-VR version will allow you to freely access the VR version once it is released. That exact release date is undetermined as of the time of this publication, but should not be too far away.

This article was written by Heather Newman, a freelance writer with work appearing in publications like The Rolling Stone/Glixel, Forbes, and VentureBeat. Follow her on Twitter: @Gbitses.

Featured Image: Obduction’s Soundtrack Art, by Robyn Miller