There is a multitude of scientific studies on how complex memory is. How audio, smell, even taste, can take you back somewhere. That is to say, sensory immersion can help stir recollections and feelings of that past. What better way to immerse yourself and stir up emotions than with an immersive medium like virtual reality?

Draw Me Close is a project from Canadian playwright Jordan Tannahill. Tannahill worked with illustrator Teva Harrison and developer All Seeing Eye, through a partnership with Canada’s National Film Board and the UK’s National Theatre. It is about Jordan’s relationship with his mother, who was diagnosed with stage-four cancer two years ago. It debuted last week at the Tribeca Film Festival. This singular virtual reality experience may be one of the most immersive so far.

“I knew nothing about the form. As I became more familiar with it, several exciting affordances emerged: Its immersive and interactive capabilities. The ability to ‘enter’ an animation and move about within it. The way VR seems to exist within a liminal space between dreaming and waking,” Tannahill told Upload.

Stepping Back Into Childhood

Draw Me Close begins by taking off your shoes. You are stand on a path of outdoor tiles, like for a garden walkway, with plants beside you. You feel the stone beneath your socks. You are standing in a five-foot square room, surrounded by beige curtains. The attendant helps you put on your Vive and a pair of fingerless gloves that place Vive Trackers on the back of your hands. Then you are in an empty space of white, except for a simple outline of your tracked hands.

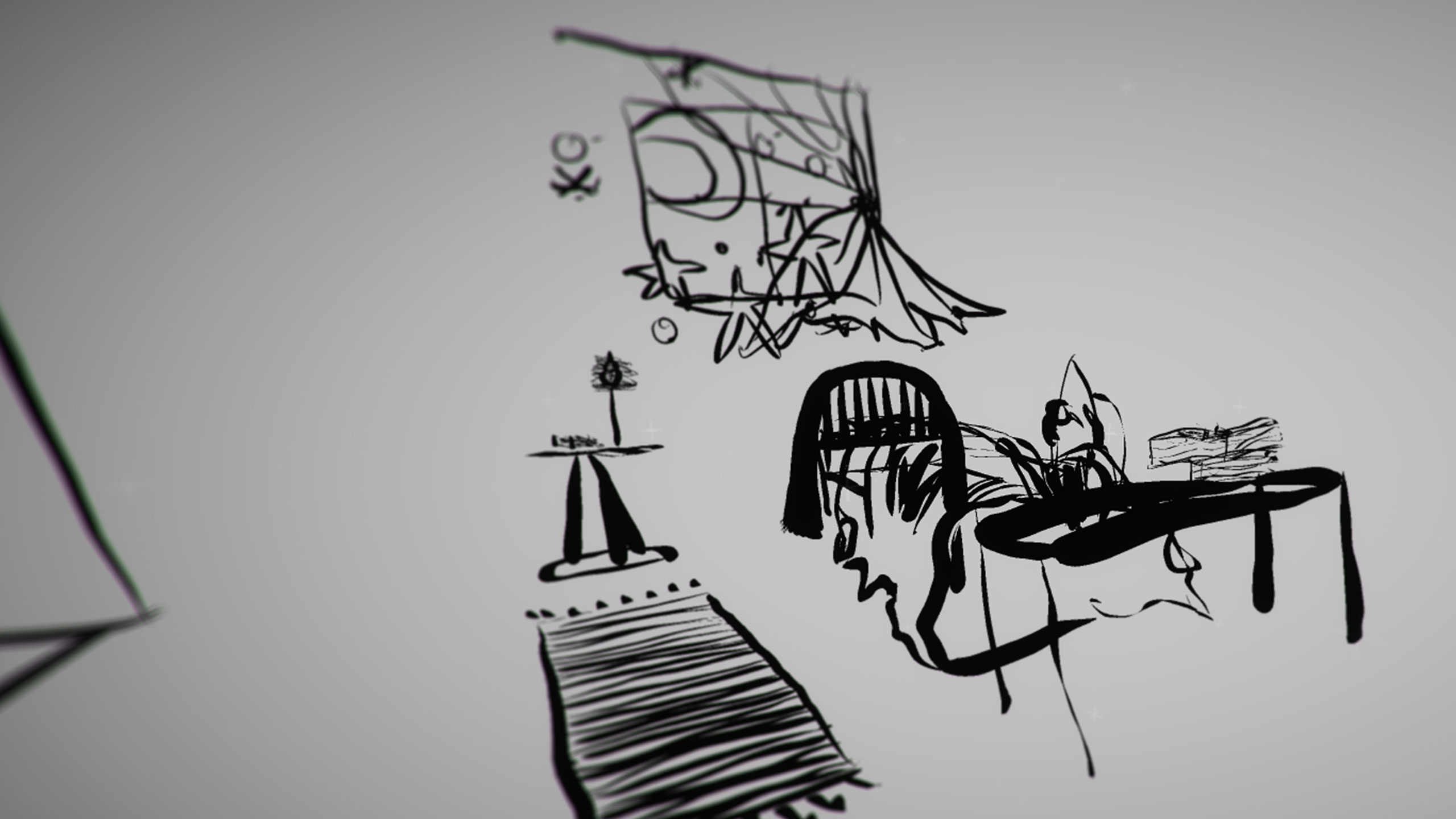

Black lines begins to draw the outlines of objects, creating a black and white world like a drawing made with a black Sharpie marker. The outside of a surburban home begins to take shape, you standing on the path to the front door. This art is the work of artist Teva Harrison, who has written and drawn about her own experiences with cancer in the book, In-Between Days.

“VR has a lot of possibility, in terms of different ways of communicating straight to the heart of the viewer, in a way that is difficult to without an immersive experience,” said Harrison. “The house is Jordan’s childhood home. He sent me streetview pictures to make sure I lined it up with the specificity of his memories. And that’s where the commonality of human condition is found, the really specific memory.”

Jordan’s voice explains how when he thinks of his mother, he thinks of his childhood home — and not when he was a teenager living there, but when he was five years old. He then says in this imagining of memory he walks up to the door and opens it. And so I did, swinging open a physical door, my socks stepping onto plush carpet.

This door is the first of several physical interactions in the experience, adding another level of sensory immersion to Draw Me Close. While virtual reality thus far is mainly an artform of sight, sound, and of mind, by adding visceral properties that you touch, it feels more grounded and real.

Now in the carpeted living room being drawn into being, Tannahill talks about hearing his mother’s car pull up. And even the sound of the car starting to evoke thoughts and feelings about her. And then she enters the space with you. The performer playing Jordan’s mother is tracked in VR too, also a line drawing of a woman in a housedress. Her pleasant and soothing voice tells you that she saw you opening the door. She hugs you hello. And then she says you smell sweaty from playing outside and you should open the window to let the breeze in. And then you do go open the actual window.

The experience’s use of props is a reminder that Tannahill and many of the behind-the-scenes principals come from the theatre world. And after the experience, I wondered how each prop and its effect was achieved. The producers didn’t want to reveal all the details.

“There is both some rough magic, as the theatre term is applied, as well as hi-tech stuff. Ultimately whatever solution worked in the simplest, most elegant way, is what we used. So there is a mix of those kinds of things. It’s about trying to keep it simple, but not too complex,” said David Oppenheim, producer of Draw Me Close, from the National Film Board of Canada.

The attendant asks you when she helps you put the headset on if you are okay with light human touch. I said I was, thinking of haunted houses and horror VR experience I’ve had in the past. Those quick touches and minor jolts were made to surprise you, jump scares to get your heart beating. But here, your mother hugs you. You can hear her moving in the room with you, see her drawn form in front of you, and feel her presence. It makes it feel real.

Tannahill said, “A lot of VR seems to negate the body. I did not want to design another experience for floating heads. As a theatre maker, the human body is one of my core tools. It was important to me to craft an experience that was tactile, that invited full awareness of one’s own body and the body of another. I wanted to invoke the idea that this childhood memory has come to life so vividly it can be touched and interacted with.”

The rest of the team worked with Tannahill to figure out the best use of the interaction with the performer playing Jordan’s mother. Yes, there are VR experiences that use haptic vests and vibrating chairs to add to the experience, but isn’t actual human touch more immersive?

“People refer to the haptics in the experience. We didn’t tell Jordan or the other artists, ‘You need to have a live component.’ It’s not to say that everything we will work on will have performers in it. But this one, it made a lot of sense. So why not work with human haptics? The touch and the carpet, and stuff like that? We don’t have [haptics tech].”

They worked with HTC to figure out a solution for motion capture. They ended up working with IKinema who has a mocap suit that incorporates six Vive Trackers. This Orion suit, coupled with the actress’s performances, brings Tannahill’s mother into VR.

Now Mother says we should play together. She brings over a poster-sized piece of paper and hands me a marker. It feels like a real marker in my fingerless gloves, but is tracked in space. She gestures for me to sit on the carpet and draw. I plop down onto the carpet, which is an action I probably haven’t done since my own youth, and with the marker I begin drawing on the paper. And the lines I draw are appearing in this virtual world of black and white, though my lines are a rainbow of colors. I chuckle at the novelty of it.

She begins to talk as a narrator then, taking over for Jordan’s digital voice for the rest of the piece. She describes the wonder of watching me draw, of watching me enjoy myself. She then joins me and we both draw on the paper, narrating that we giggle together from the fun. And it really did make me want to laugh with her. And so I did, quickly and easily agreeing to role-play the situation.

“In the very beginning, Jordan communicated that he wanted to work with illustration in VR. Then the idea of a live actress in the space with some form of motion capture came in. Which seemed really progressive and an interesting challenge. The only props we had at that point were the paper and the markers. But when we were getting ready for the lab, an order went through for a piece of carpet. Now I see how important the carpet is, as a tactile message and reinforcement. And it feels like an ’80s carpet,” said Toby Coffey, Head of Digital Development at National Theatre, and a producer on Draw Me Close.

And this is where the experience takes a turn, Jordan uses his own personal experience to move the project beyond instilling you with a sense of childhood to empathy of his and his mother’s specific circumstances.

She lifts the paper from the floor, and describes that the marker has bled through to stain the new carpet. And you do see the colorful lines there in VR. She then describes the horror she sees in your face and the horror that is plain on her face. You watch as she frantically scrubs the marker away with cleaning supplies, your mind already beginning to dread what is to come.

But once the scrubbing is finished, she instead says it is time to cook and eat dinner. Her narration then says that after dinner she would tuck you into bed. The scene fades and redraws itself into a bedroom. She takes you by the hand to the bed and lays you down. She tucks you in, pressing the blanket close to your legs and your sides. She wishes you goodnight.

She then narrates as you watch her leave the room and enter her room next door, the wall to your parent’s room disappearing. She simply narrates how you hear her and your father argue. How you hear the sounds of him hitting her again and again. How you hear her crying in the middle of the night. You watch her sit on the bed, scrunching herself up protectively.

She describes your feelings of powerlessness and your vow that one day you will be able to help her. And then she sings a slow, sad lullaby. And then everything fades to white. You are left warm in the bed, your mind filled with a melange of childhood nostalgia and pain for what Jordan and his mother experienced.

“The piece has given me a meaningful context in which to talk about death (and life) with my mother. A rather beautiful ritual of conversation has been born between her and I because of this piece. She lives in Ottawa and I live in London. Though when I am in the piece we are together again, in the same room,” said Tannahill.

Bringing Artists Together To ‘Draw’

Coffey and Oppenheim met at a documentary film festival in Sheffield, England. That very day they decided to work on something together, a project for virtual reality. In December 2016, they invited four creative minds from the theatre world to their offices in Toronto for a week. They studied and experienced what VR can do. They played some videogames with a heavy story. And they brainstormed what they could make. Out of that workshopping came Jordan Tannahill’s concept of a memoir about his mother.

At first it was purely VR, but as the project warranted it, they started layering elements from theatre. Tannahill is a playwright and both producers had experience with interactive theatre. Tannahill brought in Harrison on day two, to illustrate the project. She spent one day in Tilt Brush to get a sense of what VR illustration could be like, and then she was off and running. Designer Ollie Kay would also join to complete the visuals of the project.

The prototyping workshop then went to London for two weeks. And working with All Seeing Eye, they built a prototype experience using Unity. All along the way, the project continued to evolve. Tannahill’s discussions with Harrison, with the developers, and with performers, would result in further modifications to the script and the overall experience. And the result is Draw Me Close.

“There is something incredibly beautiful going into these virtual experiences. You go in with these expectations. The expectations may be to be in your head, to be ungrounded. But these touch points ground you in the experience and in Jordan’s story in a way that is powerful,” said Harrison. “It’s a really beautiful example of form following function. Those touchstones, our sense memories, are so rich. The act of feeling, the act of engaging with the space around us, takes us back — the taste, the touch, the feel — in a way that nothing else really does.”

Like many other VR projects at Tribeca, this iteration of Draw Me Close is just the start. Oppenheim describes it as a shortfilm version of an eventual feature film/play that is 60 or 70 minutes long. That extended version will take shape over the next year or so. They are unsure what form such a fusion of theatre and virtual reality will ultimately take.

“This is a shortfilm version of a 60-, 70-minute play. It will tell the story of Jordan’s relationship with his mother, over time. We don’t know yet, in terms of form, whether it will be one-on-one, whether it will be on stage with an audience, or whether it will be some other fusion. But in terms of story, it will trace that relationship and what happens when one member of that relationship starts to gradually disappear,” said Oppenheim.

Besides the issues of distribution the producers have to consider for the final version, since you can’t just download this from the Vive store have the full experience with the props and the performer, there are more emotional issues to be addressed.

Coffey said, “One of the things we didn’t anticipate, and we will have to for the one-hour version, is our duty to the audience. It’s incredible how many people have a strong experience. How contemplative they are about their own story and experiences. People can be really grounded or affected by [Draw Me Close]. So we got to really be careful when we are doing the extended version, to look to be there to help people afterwards. It’s not everyone walks out when the credits start. It’s going to be something where there’s an opportunity to talk at the end.”

Whatever the memoir is eventually shaped into, there is no denying that this current experience for Draw Me Close is powerful. The fusion of room-scale VR, stylized art, tracked hands and objects, interaction with the set and with an actress, come together to make an immersion into childhood that delivers an emotional gut punch. It is a unique piece of art that is only possible with the aid of virtual reality. And that may be just what VR needs.

“At the moment VR still feels quite niche; largely confined to more rarefied contexts like galleries, festivals, and tech fairs. The major hurdle facing the form is how to scale it up. As humans we want to experience narratives collectively. This is the great enduring success of theatre and cinema. As long as VR remains an atomised, singular experience, I suspect it will have difficulty moving beyond these more insider contexts.”

“VR still feels as if it’s in the proto phase that cinema was in the 1910s, where the spectacle of the form supplants narrative and conceptual nuance. It is a form in search of its auteurs, but it will find its Tartovskys eventually,” Tannahill said.