It’s 1916 and I’m standing in the war torn streets of Dublin, Ireland. A thick cloud of misery clings to the greyish air, given form by lofty plumes of smoke that circle around. A torrent of gunfire and explosions deafen me as militia forces seek cover at a nearby wall. Standing beside me is William McNieve, a young fighter that will survive this historic conflict, a scramble for national independence dubbed the Easter Rising. I know that because it’s his recount of this bloody and oft-forgotten event that’s made this fascinating VR experience possible.

Easter Rising: Voice of a Rebel is what the piece is called, and it’s made in collaboration between the BBC and London-based Crossover Labs as well as being directed by Oscar Raby of VRTOV. If you have an Oculus Rift you can already try it out for yourself for free via the BBC Taster site, and I really recommend you do.

It’s an engaging 12 minute piece, artfully told by redubbed narration from a tape recorded by McNieve years after his experience. His words literally paint the scenes we experience, which detail the six day conflict that began on April 24th. Crucially, its delivery leaves an impact that’s not soon forgotten; even a few weeks on from trying it for myself I can still remember vivid images and dramatic moments. If we’re still at the stage of VR having to prove its worth to the documentary genre, then this certainly makes a good case for it.

Raby himself could do that just by talking to you. Having already worked on a deeply personal VR experience, Sheffield Doc/Fest 2014 award winner Assent, he’s positively energised about the tech as a tool for storytelling. As we chat at this year’s iteration of the festival, he corrects my use of the word ‘camera’, noting that both he and those he works with are conflicted about using traditional terms for storytelling in a new medium. “That brings about the filmmaking establishment,” he explains. “Whereas it could be many other things; it could be the eye of the user.”

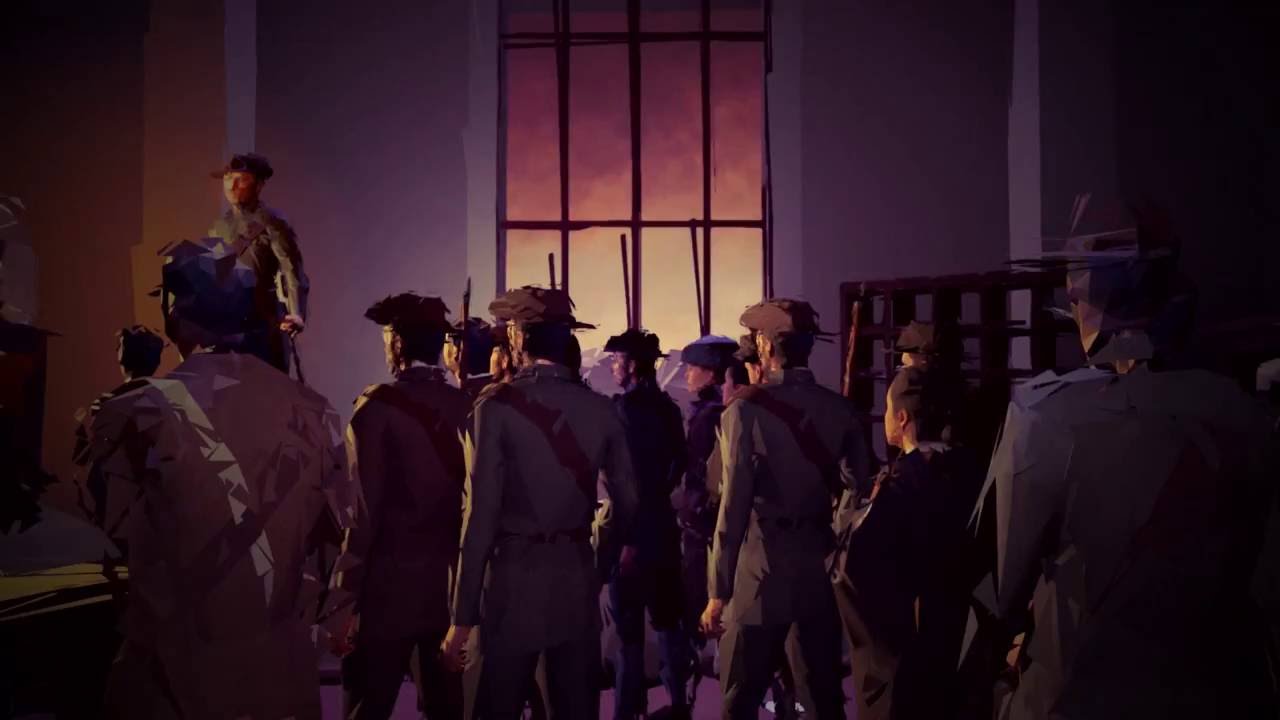

Touring the streets of Dublin in his latest piece, I get an understanding of what Raby means. I don’t want to call the grimy pavements and packed out halls a “set”, because I’m there. I’m not under the control of the director himself; I decide the angles and the focus that I bring to the story. “We want the user to have interactions, not just to stare around themselves but to also understand the core of the story through the actions they perform,” Raby says. He wants viewers to “own” their experience, not have it dictated to them.

Inference was a common theme in the piece’s creation, in fact. Raby talks of the process of interpreting the words he heard from McNieve, comparing it to an artist preparing to paint on the same subject. “They do something with brush on the canvas in that moment is an interpretation. It’s not a photorealistic depiction of the event. So we’re going for that, the reconstruction and the letting the medium speak around the facts that we are feeding into it.”

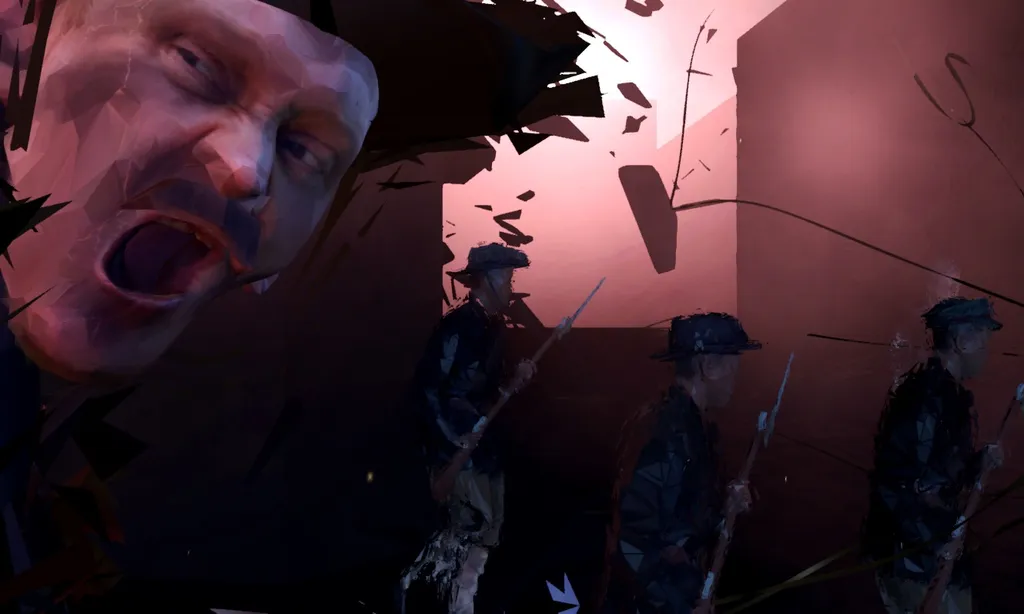

And, no, the experience’s visuals are far from realistic. They remind me of The Night Café somewhat, possessing and oil-like quality, only with objects and environments split apart and fragmented, as if we ourselves are trying to piece the events together from memory as McNieve talks.

That said, faces are strikingly clear, as if to haunt you long after you’ve taken the headset off. According to Raby there’s a “sweet spot” between one and four meters away from the viewer. “That place is where a face shines in VR,” he explains. “You can see the eyes, you can see the face, you can see the textures. Even if they’re not realistic they seem to be there with you.”

What that does is humanise an event that’s long been confined to text books. Even now it’s what I remember most about Easter Rising; the cold, determined stare of soldiers that slowly see the odds shift against them. It helps to make an explosive final few minutes all the more harrowing.

Maybe this will fade as VR grows in prominence, but ultimately I keep coming back to just how memorable Easter Rising: Voice of a Rebel is, and what that could mean for the future of VR documentaries and education. I made eye contact with people, creating images that have stuck in my brain. I made myself jump by turning round to face a crowd of rebels. My eyes widened as an explosion emitted a brilliant white light. These things happened to me and I remember them just as I remember real life moments. That is the power of reconstructing these events in VR.

Looking forward, Raby wants the genre to expand into large, more fleshed out documentaries. He boldly wonders about a 90-minute VR film, only split up episodically for those that can’t quite stomach the thought of spending that long inside a headset.

Personally, I can’t help but think about how incredible behind-the-lines works like the recent Cartel Land would be enhanced in VR. Imagine being able to recreate dangerous real world situations from the present day and using that as a tool to raise awareness of just how bad things really are in some parts of the world.

Or think instead of expanding on the historical element that Easter Rising touches upon. We could reimagine stories of the two World Wars, or put ourselves in the assassination of JFK. With VR, the world today is our oyster, but its history is just as compelling.