Meta Platforms ended 2021 with more VR headsets running Quest’s system software than any other headset maker.

Will that be the case again in 2022? If so, for how many years into the future is Quest likely to be the gateway to VR and AR for the vast majority of people everywhere? And why did Facebook become Meta Platforms near the end of 2021?

“Mark Zuckerberg has decided it’s time to build the metaverse,” Doom programmer John Carmack told an audience in October.

What is the metaverse? I could cite its origin from the book Snow Crash but ultimately the word means whatever Zuckerberg wants it to mean. He owns Meta.com, likely has millions more Meta headsets in the market right now than the nearest competitor, and told investors he’ll spend more than $100 billion in the next decade working to make “Meta Platforms” a leader in the next generation of personal computing. The “metaverse” is an “embodied internet”, he says, but it is also what he’s calling a fairly broad effort to align public perception with the long-term vision in his head for the company he wants to build.

This is some of the context for that comment from Carmack. He’s an expert technical mind who is now working on, as Wikipedia defines it, “Artificial General Intelligence” or the “hypothetical ability of an intelligent agent to understand or learn any intellectual task that a human being can.” Before that, he was a rocket scientist and then became a key part of Oculus. He’s independently wealthy, so he can do whatever he wants, and he’s convinced that if someone builds something like Skynet they can still “shove the AI in a gym locker if necessary.”

“The AI can’t ‘escape’, because the execution environments are going to be specialized — it isn’t going to run a fragment on your cell phone,” Carmack wrote in November.

And still, despite this focus, he uses some of his time as “Consulting CTO Oculus VR” to advise Meta’s incoming CTO Andrew Bosworth in the way Sherlock Holmes advised Scotland Yard on difficult cases. Put another way, Doomguy doesn’t need more money and he has bigger fish to fry than Facebook or Zuckerberg. So here he is addressing the moment in time for Facebook, Oculus, and Meta:

“But, you know, here we are” pic.twitter.com/gfKrYAGhHp

— Ian Hamilton 🚘 GDC 2023 (@hmltn) October 29, 2021

I appreciate this comment as a key one to remember from 2021 because Carmack’s “here we are” comes at the moment when so many people first hear the full vision Zuckerberg is pitching for Meta.

2022: A Key Year In Personal Computing

Zuckerberg was born around the time of the first mass market personal computers. During his infancy, people were starting to buy hefty boxes they put on their desks that made it possible to accomplish any number of tasks, from playing games to writing stories. He was just a kid when people started hooking these boxes up to the Internet in large numbers and using them to look up information or connect to people in real-time. And when Zuckerberg started Facebook in 2004, not everyone had cell phones.

How different was person-to-person communication in 2004?

“Cingular and Verizon sell entry-level packs of 100 messages for $2.99 a month, and T-Mobile offers 300 for that price,” a NY Times article dated from that time listed. If you wanted to send photos to a friend it cost a lot more. “Verizon’s price is 25 cents apiece, but it also deducts the time it takes to send or receive messages from the voice minutes on the customer’s calling plan.”

Apple’s iPhone and Google’s Android obviously helped change that from about 2008 onward. Since then we’ve been living in a world where some of the rules are established by iOS and Android. For example, if you wanted to publish a high-quality app on one of their devices you typically pay 30 percent to Apple or Google’s platform and agree to abide by its rules. This is one of the key paradigms of personal computing that shaped Facebook. A free website for college kids to connect with friends grew into the largest most easily searchable database of humans on the planet, and Zuckerberg’s path to growth went the way it did partially because Facebook was born into a platform war waged at least one layer above it.

Handing over 30% of a sale to a popular platform’s only storefront certainly allows plenty of new ideas to flourish, but it also carves out an obvious advantage for the platform itself and forces new platforms to pick other paths to the future. And anytime the people running the platform see an opportunity for a competing service they have a margin allowing them to do it cheaper. The 30% rule can also be lightly (or selectively) enforced in private under the guise of fairness to other developers, and failing that, there’s a very straightforward path to removal from the platform. Just download Epic’s Fortnite from the Apple App Store to see how that rule is playing out.

Meta can be seen as Mark Zuckerberg’s effort to level the playing field with Apple, Google, and others. Over the past 7 years, Facebook built, sold, shipped, updated and ended either support or game development for three different VR platforms already — Gear VR, Oculus Go, and Rift. Zuckerberg moves fast. If you have an original Oculus Quest from 2019 you’re already feeling the pinch of obsolescence. Even if you bought an entry-level Quest 2 before July of 2021 you might be feeling a little outdated already. That 64GB headset provides just enough storage for Medal of Honor and little else. Yes, Zuckerberg moves fast, so fast that he’s left behind millions of early adopters who bought an Oculus-powered headset that was part of a platform Meta has since moved its focus away from.

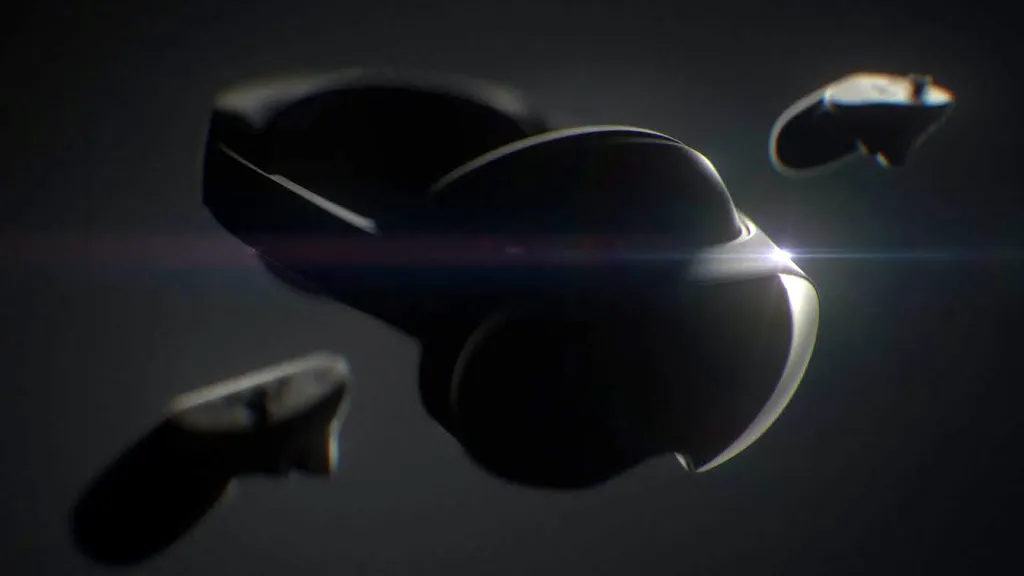

Next up is project “Cambria”, which Zuckerberg said:

“This isn’t the next Quest, it’s gonna be compatible with Quest, but Cambria will be a completely new advanced and high-end product, and it’ll be at the higher end of the price spectrum too. Our plan here is to keep building out this product line to release our most advanced technology before we can hit the price points that we target with Quest.”

Is Meta’s Cambria headset a new platform?

Based on the comment above we know Cambria will run Quest apps, but perhaps with some new APIs that serve as extensions for existing ones?

Meta released avatars, for example, which can be used across not just Meta headsets but SteamVR headsets as well. Cambria will animate avatars like these with a real-time stream of its wearer’s actual facial expressions. That sounds interesting, but how do I turn it off? What if I don’t want my expressions cast over the internet? What if I don’t want them sensed by my headset at all?

Another new feature for Cambria is likely to be more robust environmental understanding with color cameras for some really compelling AR or mixed reality experiences. There’s a passthrough API on Quest that developers are playing with, but it’s a pretty jarring experience right now given it is black and white and the environmental understanding is so limited.

A headset that understands more about the world around it might be able to more actively assist people. What happens when you can use a VR headset with great passthrough to measure any object without a physical tape? What if you could look at a whiteboard and copy text hand-written on it? How about being able to look in your fridge and see the expiration dates for the food automatically hovering above the food? What if you gave Cambria a good look at everywhere you store food and it suggested some recipes for the ingredients you have on hand that are going to expire in the next few days?

Taken a few steps further — you can start to imagine how cooking might change with really good AR glasses and an active virtual assistant helping you along. A VR headset that runs Quest-like apps, understands the objects in your home, and actually works outside the home as well? From physical fitness to our fundamental understanding of the natural world, such a device might serve as a development platform for a new class of AR or mixed reality app that starts to fundamentally change what it means to live, learn, and get things done in the 21st century. Is that what Cambria is meant to do?

Are we in the “pre-Cambrian explosion” era of history for spatial computing apps? What will the next generation of headsets like Cambria begin to change about their paradigms of communication and personal computing?

2022 for Meta is looking like a year of updating, streamlining and super-powering the purchase of Quest while presumably seeding developers with new Cambria-connected APIs and shipping this higher-end device to people who can afford the extra price.

Even if you listened to him in the video embedded above, read a lengthier transcript of what Carmack said edited for sentence fragments and bolded for tl;dr:

I was quoted all the way back in the nineties as saying that building the metaverse is a moral imperative. And even back then, most people miss that I was actually making a movie reference, but I was still at least partially serious about that. I really do care about it and I buy into the vision, but that leaves many people surprised to find out that I have been pretty actively arguing against every single metaverse effort that we have tried to spin up internally in the company from even pre acquisition times. I want it to exist, but I have pretty good reasons to believe that setting out to build the metaverse is not actually the best way to wind up with the metaverse. And my primary thinking about that is a line that I’ve been saying for years now, in general relation to my arguing against these efforts, is that the metaverse is a honeypot trap for architecture astronauts and… architecture astronaut is a kind of chidingly pejorative term for a class of programmers or designers that want to only look at things from the very highest levels, that don’t want to talk about GPU micro architectures, or merging network streams, or dealing with any of the architecture asset packing, any of the nuts and bolts details, but they just want to talk in high abstract terms about how, ‘well we’ll have generic objects that can contain other objects that could have references to these and entitlements to that and we can atomically pass control from one to the other.’ And I just want to tear my hair out at that because that’s just so not the things that are actually important when you’re building something. But here we are, Mark Zuckerberg has decided that now is the time to build the metaverse. So enormous wheels are turning and resources are flowing and the efforts definitely going to be made. So the big challenge now is to try to take all of this energy and make sure it goes to something positive and we’re able to build something that has real near-term user value because my worry is that we could spend years and thousands of people possibly and wind up with things that didn’t contribute all that much to the ways that people are actually using the devices and hardware today. So my biggest advice is that we need to concentrate on actual product rather than technology architecture or initiatives.

Quest 2 as it stands today represents half a decade of winnowing VR technology to arrive at the exact feature set millions of people want in an all-in-one VR package offered at the lowest price possible. Quest 2’s price has been described as “unbeatable” — why wouldn’t Meta just focus on creating more “real near-term user value” there that contributes to “the ways that people are actually using the devices and hardware today”? Does splitting consumer, developer, and employee focus between Quest and Cambria make sense right now?

What’s Next For VR And AR?

Is Mark Zuckerberg the architecture astronaut behind Meta Platforms?

Meta executives understand Cambria is unlikely to sell as many units as Quest 2, and more capable mixed reality devices can unlock a lot more uses for people than today’s bare minimum priced-for-mass-market hardware. If the biggest Internet-connected platform the world has ever seen is yet to be defined by anyone, and Cambria becomes Meta’s true starting place for that final all-encompassing “reality” platform? Well, that means the sensors and design choices in Cambria matter a great deal.

We also know Apple is preparing its own VR/AR headset and rumors are it’ll be pretty sensor-laden itself. Apple’s iOS platform is home to expression-driven avatars who can stand in for you if you don’t feel like having actual “FaceTime” with somebody, and you can already measure things in the open air with iOS or copy hand-written text off a whiteboard. You can even use SharePlay for a pretty robust distance defying content sharing experience that includes watching movies together, similar to Bigscreen.

From Meta’s Cambria, Horizon Home, and Messenger to Apple’s Oak, rOS, and FaceTime, plus Sony, SteamVR, Microsoft, Google, Qualcomm and beyond — the next phase of personal computing could see some of its biggest platform battles play out in the coming year.