Farpoint, Sony’s first stab at an AAA first-person shooter for PSVR, is sold to you as the action game of your dreams. Finally, a chance to feel like you’re really in the movie, unleashing a fury of lead upon your enemies. Gear up, pull your headset over your eyes and get ready to do your best Colonial Marines impression.

Unfortunately, this is a game that takes a bit too much inspiration from Aliens, and it turns out I’m more Hudson than Vasquez.

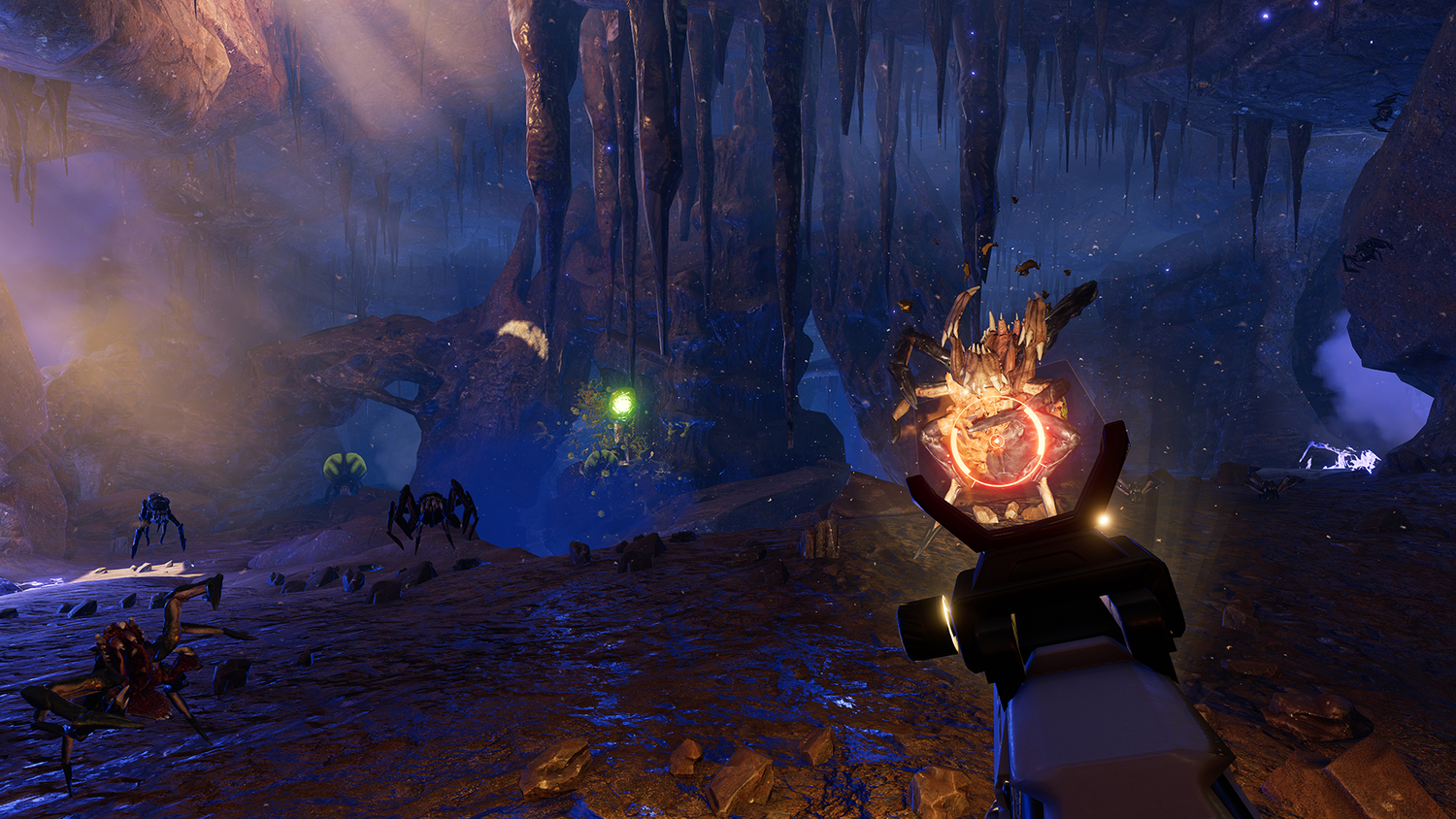

Impulse Gear’s shooter, the first to use the PSVR Aim Controller, features spider-like alien enemies. For the most part, they’re large enough not to trigger any dormant arachnophobias, but there is one common enemy type — essentially cannon fodder — that’s just small enough to creep you out significantly. Worse yet, this foe likes to leap directly at your face, Xenomorph-style. Their very presence keeps you constantly on edge, your finger running up and down the Aim’s trigger, ready to pull at the slightest sound. Developers long to create this kind of tension in traditional gaming, but it’s quickly achieved in VR with baddies like these. Just because something like this can now be done easily, though, that doesn’t mean you should do it all the time.

What I’m talking about here goes beyond simply acting tough. This isn’t even a call for less horror games; I scare easier than most, but I still bravely fought my way through Resident Evil 7. With Farpoint, though, that’s not what I thought I was buying into, and certainly not the type of experience I was hoping for. I haven’t seen these spiders in any trailers, age rating boards only warn of ‘Violence’ and ‘Strong Language’ and they weren’t as prominently featured in my earlier demo of the game (though, admittedly, I could have paid better attention to the screenshots). While I’ve managed to find coping mechanisms that are helping me to inch my way through (though still not without a steady supply of screams), the lack of confidence and trust I now feel at every point in the game is robbing many of its more interesting moments of their intended emotions and it’s not the first time I’ve felt this in VR.

While wearing a VR headset to transport to a virtual world — even one that isn’t intended to be a horror experience — even the slightest scare can completely destroy the trust between a player and a developer. With the best of intentions, a developer is essentially taking advantage of you and your relative comfort to elicit a strong reaction. But, while a loud bang might make me jolt out of my seat in a normal game, the same scare in VR can have me momentarily but very genuinely fearing for my personal safety, which is a highly unpleasant sensation when it’s so unexpected. What reason do I have to believe I’m safe at any point in a world if its creators take the opportunity to scare me like this even once?

This is something that I believe some developers need to learn to respect. Tempting as it is to insert the odd jump scare into your otherwise straight-faced FPS, its consequences can have more profound effects in VR than they do in a movie or traditional game, and when I learn that I’m in a world ruled by a god that likes to tease and toy with me in this way, I’m instantly deterred from remaining there. For many, that will be an unintended consequence and one that they may want to consider going forward (or not, if they, of course, feel strongly about what these terrors contribute to their worlds which they are entirely at liberty to implement).

It’s telling of the unique psychology we build up when in VR worlds compared to flat worlds. If I’m in the real world and I reach out to grab something and I get an unpleasant shock, I’m not going to reach out for it again. Why, just because I’m in VR, should I continue to put myself at risk to those shocks when I don’t desire them? If I’m playing an otherwise unscary adventure game and a zombie grabs my hand as I reach out for a weapon, I’m going to have unwanted hesitations about grabbing items for the rest of the game.

And so it was with great discomfort that I pigeon-stepped through many of Farpoint’s calmer, more intricate moments. I didn’t know whether to feel enchanted or threatened by a hovering light fluttering through a darkened canyon. I was too distracted by the advent of more creepy crawlies to really care. Rather than throw myself into the game’s bigger action setpieces, I have to hug the wall with my back and find a place with a clear line of sight so as to avoid unwelcome surprises. I’m fairly sure this isn’t the way Impulse Gear wanted me to experience Farpoint, but it’s the only way I feel even remotely comfortable playing it, and even then I’ve only managed it in short bursts before I have to rip the headset off of my face, and I know I’m not alone.

Heck, even if this was the feeling Farpoint wanted to inject into me, the box should have come with a warning along the lines of “Featuring: Half-Life’s Head Crabs Really Trying To Eat Your Face Off”. If you’re just going off of trailers alone it’s frankly unfair that you might spend $75 on a game and controller only to find out you can’t bring yourself to play it.

I’ll come away from Farpoint not with the same set of gripes we laid out in our review earlier this year, but instead a gnawing frustration that I wasn’t able to experience the game to its fullest because of this one enemy type. VR scares can be compelling and memorable, but they can also work to undo everything else you’ve carefully crafted over years of development. The next time you’re making your monster closet, think about the type of world you really want to create, and the trust you build with your players.