When the printing press was invented Conrad Gessner feared that it would cause an information overload that would be harmful to people. When radio, television, and, of course, video games made their debut, people worried about the possible effect these might have on human psychology. It is reasonable to assume that media, in general, affects people but, more often than not, the fears surrounding new technology are unwarranted. Still, it’s always good to perform your due diligence as we travel into new frontiers. Virtual reality is a new frontier.

Dr. Michael Madary is excited about the prospects of virtual reality. To preface our interview, he is very clear that he is not arguing for any sort of censorship or restrictions on the technology. “VR is a new medium and offers great opportunities for artistic expression,” Dr. Madary explains. “It would be a mistake to place hasty restrictions on that self-expression. Keep in mind that some of the great literary works of the 20th century had to battle censorship. Also, government censorship runs the risk of banning content for ideological or political purposes. It is preferable for the industry to self-regulate in order to avoid a perceived need for government interference.”

In an article he penned alongside Thomas K. Metzinger, Madary says that “in principle, the individual citizen’s freedom and autonomy in dealing with their own brain and in choosing their own desired states of mind (including all of their phenomenal and cognitive properties) should be maximized.” Regardless, he tells me, “users should be aware that we really don’t know what the effects of VR are but there are preliminary studies that suggest there are influences that people don’t even notice.”

Dr. Madary was part of a 5-year research program called Virtual Embodiment and Robotic Re-Embodiment. Part of his role on this project was to investigate the “foundational issues in the applied ethics of VR, with a heavy emphasis on recent empirical results.”

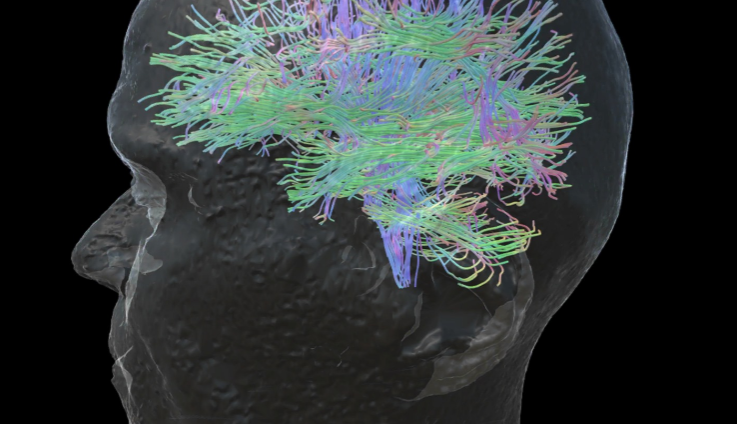

When it comes to virtual reality, as compared to other media, Madary says, “VR, as you might guess, is a more powerful illusion than, say, reading a novel, or watching a movie, or even playing a traditional video game because it really targets the parts of our mind, or that parts of our brain, if you will, that give us a sense of reality.” This power warrants his investigation since it opens up opportunities for deep behavioral manipulation.

As evidence, he cites a research project performed by Domna Banakou, Parasuram D. Hanumanthu, and Mel Slater that demonstrates how virtual reality can reduce implicit racial bias in white people. The project itself puts people in either a white or black body and has participants follow the movements of a virtual Tai Chi instructor who is either Asian or European Caucasian. The results show that participants scored better on racial bias tests after being immersed in the virtual reality environment than before. If virtual reality can have positive effects like this, then is it not reasonable to suspect that it can have negative ones as well?

It is clear that the human mind is sensitive to context. The famous experiment, referred to as the Stanford Prison Experiment, led by Professor Philip Zimbardo, seems to prove this. In the experiment, roles were assigned to subjects; they would either act as a prison guard or a prisoner. In the end, a portion of those assigned the role of prison guard, as a result of their perceived power, resorted to authoritarian measures and subjected those in the role of prisoner to psychological torture. Many of the prisoners were submissive in nature and accepted the power given to the guards. Zimbardo’s ultimate conclusion was that behavior can be shaped by situations rather than by personality.

A similar result, called the Proteus effect, occurs in digital spaces such as virtual reality. In essence, the Proteus effect describes how the physical characteristics of an individual’s avatar within a virtual environment shapes their behavior. It proposes that people perform differently based on the expectations placed on them as a result of the way they look.

In one study, women were put in the body of two different types of avatars. One was highly sexualized while the other was not. They then were asked to face a virtual mirror for a bit. In a subsequent conversation with a male avatar, the women in the sexualized avatars reported being more conscious of their body image.

Madary believes strongly in the need for his research. “My background is in philosophy,” Madary says. “The philosophical tradition, now supplemented by empirical results from psychology, contains valuable insights about consciousness, agency, belief, and human flourishing. Immersive technology can target all of those areas in ways that no other non-invasive technology can. I think it is important to use those philosophical insights as a basis for determining how we should (and should not) use immersive technology. More generally, I want to encourage people to question the assumption that technological innovation is always good. We should ask whether particular innovations help us to flourish as human beings.”

As such, Madary has a list of recommendations that developers, researchers, and users might heed.

One of the most prevalent recommendations that Madary makes, to my eye, is one pertaining to informed consent. Specifically, he states, “informed consent for VR experiments ought to include an explicit statement to the effect that immersive VR can have lasting behavioral influences on subjects, and that some of these risks may be presently unknown.” While his recommendations are specifically made for research settings, I can certainly see the merit in reminding users that VR can have long lasting behavioral effects on subjects.

Another concern lies in the development and use of military applications. Madary believes that these sort of applications, “should be closely monitored by policy makers and funding agencies alike.” He goes on to say that torture within virtual reality is still torture.

Madary also has some recommendations for more general users. He believes studies should be done to discover what might happen over increased virtualization of social interactions. If there are effects, he wants to know what might be lost in social interactions mediated by advanced telepresence in VR and, if there are losses, how might they affect the human self-model.

It is also prudent that we are well-informed when it comes to market research via virtual reality. According to Madary, users should be aware that evidence exists that advertising tactics using VR could have “powerful unconscious influence on behavior.” Furthermore, data could theoretically be collected through new means of surveillance. It could now be possible for app developers to gather data about “motor intentions” or a “kinematic fingerprint.” Were someone to gather information like this, unbeknownst to the user, it would be blatantly unethical and a clear disregard for a user’s privacy.

So what can we do? When I asked him about the responsibility of content creators in the VR industry, Madary told me “it would be helpful to develop more communication between the industry and scientific researchers. Organizations such as the Immersive Technology Alliance are in a position to foster that kind of communication, though there is much more work to be done.”

Virtual reality is a powerful technology; that’s part of what makes it so alluring. With its power, we will undoubtedly see great games and astonishing research into human psychology. It could help a lot of people. Unfortunately, at this point, we do not know what capacity there is for harm in the hands of those who do not have a great respect for ethics. Perhaps, then, we as a community should insist that those who develop applications as well as those who conduct research adopt certain best practices in the interim while we await a better understanding of the capabilities of virtual reality.