“I know you’re lying to me Joe,” my mother says making me freeze mid shoe-tie.

“N-No I’m not,” I say, a lace gripped lamely in each of my 11-year-old hands. If I can just make it another minute I’ll be out the door and on my way to school.

“Yes you are. I know. A mother always knows,” she replies, not with anger, but with that invincible faith in her own abilities that only moms seem to have. “So why don’t you try that again. When exactly is your science project due?”

I stare up into her unwavering gaze and feel my own start to falter. The jig – once again – is up.

“It was actually due two days ago,” I mumble, wishing for the millionth time that her earlier words weren’t so accurate. How, how do mothers always know?

It’s now 13 years later and Facebook is using space-age igloos to figure out an answer to my fourth grade question and solve the riddle of social presence.

Decoding The Mafia

Yaser Sheikh is the head of Oculus Research. His relaxing voice and calm demeanor contrast sharply on stage with the world-changing statements he is making.

Sheikh is speaking to a gathered throng of enthusiastic developers, journalists and tech aficionados at Facebook’s 2016 F8 conference. He is explaining how his company – and its parent company Facebook – is attempting to solve the problems that present themselves in VR socializing experiences.

“What is social presence and how do we achieve it?” He asks the onlookers.

From there, a video plays behind him depicting a group of young friends all engaged in a rousing game of Mafia.

The footage is rolling without sound, forcing the audience to reflexively rely on its non-verbal communications understanding to follow the action.

Within moments it is clear that the brunette woman in the center of the circle is lying to her friends. Almost as soon as the the audience makes this connection, her cohorts on screen begin to point and laugh triumphantly in her direction. Apparently they noticed the deception as well.

Without breaking stride Sheik begins to roll a second video. This time the depiction is of a small boy sitting with a behavioral therapist. She is attempting to determine if the boy has autism as she rolls a ball toward him. He returns the ball and then Sheik asks us to watch.

“She will now wait for the boy to indicate he wants the ball in some way,” Sheik says. “You’ll see him nod in a moment.”

As if on cue, the young boy dips his head to indicate his interest in seeing the ball return to his side of the table and a satisfied smile crosses Sheik’s face.

“You see there he made a gesture of request,” Sheik said to the crowd. “That is a universally excepted way to communicate. And yet, there is no unique word for it in any language. This is not the only one of its kind. There are thousands of unnamed behaviors like this in society.”

Sheik compares this unspecified mass of non-verbal bread crumbs to a quote from Sociologist Edward Pasir who called this phenomenon:

“…an elaborate code that is written nowhere, known to no one, and yet understood by all.”

This code, according to Sheik, is what allows a group of friends – or perhaps a young boys mother – to know when they are being lied to. It is what allows a young child to indicate to an adult that he would like to have a ball rolled to him across a table. For Sheik, unraveling this “elaborate code” is the key to creating acceptable social presence inside of virtual reality.

There are just three things that might get in the way.

Toppling The Three Giants

Now that Sheik has captivated his audience with the bright promise of a fully socialized future for VR, he now begins to lay out the blockades that lie in the way.

“There are three things we will need to accomplish in order to achieve this goal” he said as he began to outline each.

Capture subtle motions: The elaborate code is complex and detailed. In order to create real social presence in VR, Sheik explains that technology needs to be created that is capable of capturing those micro-motions, and algorithms need to be developed that can render those recordings in real time. Sheik displayed a video to underscore both how far that technology has come, and how far it still has to go.

[gfycat data_id=”ThisAnnualAnophelesmosquito”]

Display those subtleties in convincing ways: Sheik admits that in the short term VR social applications will rely on simplistic avatars. Facebook demonstrated its ability to do that during a demonstration earlier in the keynote.

However, Sheik does not believe this should – or will – be the final stop on the road to immersing users in believable digital social interactions. In fact, he also unveiled his own high-res 3D avatar made from a detailed scan of his own head.

[gfycat data_id=”CornyConfusedBorer”]

Models like these are impressive, but current technology cannot render them successfully in real time.

Overcome what’s known as “social prediction”: This is the most esoteric of Sheik’s goals. Solving it involves combining sociology with technology to subvert mankind’s inbred ability to understand non-verbal communication.

Well captured micro-expressions and believable avatars will go a long way to fixing this issue, but it will take a detailed understanding of what Sheik calls, “The vocabulary of social behavior” to truly fool the brain’s natural ability to sense communication from another person.

Now, the goal is clear – the obstacles are understood. All that remains to be done is – as a certain fictional astronaut would say – science the sh#t out of this.

Stepping Inside The Igloo

It’s called a penoptic dome and Sheikh explains to the crowd that it is Oculus and Facebook’s best weapon in the battle for social presence.

“What we need to do is captured unrestrained motion,” Sheikh says in order to explain why current motion capture suits and cameras are considered insufficient for creating true social VR.

“Observe the confetti in this video,” he said, gesturing toward the screens. “It is able to move freely inside the dome and all of those motions can be captured in real time by the system.”

[gfycat data_id=”VapidUnrealisticHamadryas”]

“But let’s see how this works with humans,” Sheikh said.

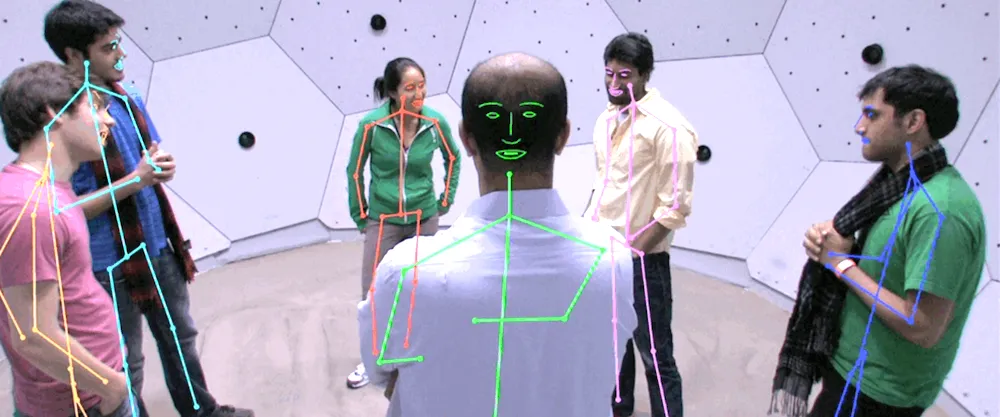

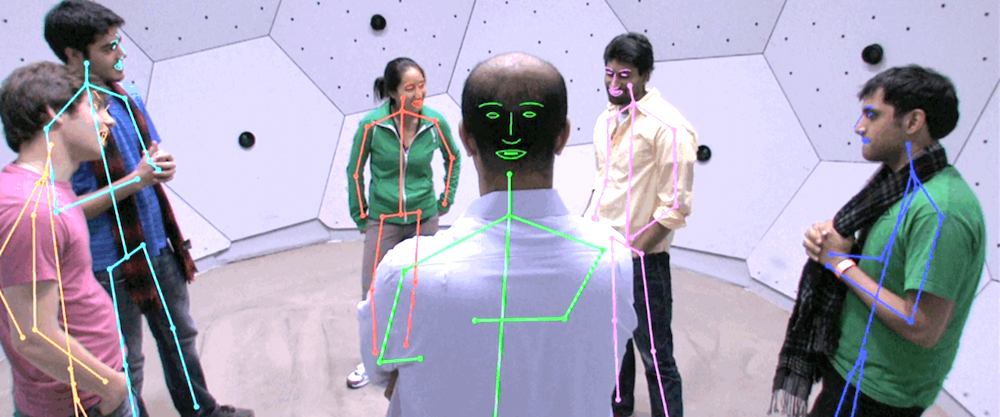

He then proceeds to show the same group of people playing Mafia from before, only now it is clear that they are in fact all standing inside of a panoptic dome. Sheik overlays each person with wire frames that correspond to key points of motion.

This has been the primary way of relaying human motions into virtual worlds: by identifying a few key points of interaction and tracking them with cameras. Sheikh, determined to prove the folly of this strategy, plays the same clip he showed before of the Mafia players and what follows is and indiscernible jumble of stick figured gyrations.

[gfycat data_id=”MeagerOrganicEstuarinecrocodile”]

From this demonstration, it’s possible to tell that someone is being accused but not to determine what exactly gave them away. And Sheikh knows it:

“As you can see, the deception could not be seen this time around,” He says before transitioning to the same scene rendered using the panoptic dome’s own motion tracking capacity.

[gfycat data_id=”UnfitMasculineAllensbigearedbat”]

“Our system tracks hundreds of thousands of points on each point in real time on each person,” Sheikh said.

As far as Sheikh and Facebook are concerned, these domes are the future for implementing social presence in VR. And they have an entire studio full of them.

A Long Road Ahead

“Obviously our goal is not to put one of these domes into each consumer household,” Sheik chuckles. “But the data they are able to collect is what will allow us to crack the elaborate code and achieve true computational interactions.”

The journey from here will be long, but Oculus and Facebook seem truly committed to creating a world where, as Sheikh puts it, “relationships are not based on location, or happenstance, but on personal choice.”