Virtual reality is about hit the mainstream, and it’s about to hit it hard. It is showing up everywhere – from being an integral part in large scale conferences to showing up at small, close knit meetups. Practically everywhere you look, VR is booting up to alter every industry it touches; but where did it all come from? Why is virtual reality proliferating into the market like never before?

In a series of interviews and re-publications, we venture into the past to see where this exciting virtual reality ride began. Today, we interview Dr. Steve Guynup. For over twenty years Dr. Steve Guynup has been involved in new media and education. First as a production artist who grew into building multimillion dollar training software for companies like UPS, Weyerhauser, CSX Rail & Georgia Pacific.

During the dot.com boom, he explored early mobile games and multi-player online games for a company in Helsinki, Finland. After the dot.com bust, he then picked up a Masters from Georgia Tech and a Doctorate from the University of Baltimore. For past decade, Dr. Steve Guynup has been teaching game design online, working with artists, and exploring untouched aspects of 3D virtual design.

Through a several email communications, we asked Dr. Steve Guynup what the culture what it was like then and how it is similar/different from what is occurring now. So sit back, relax, and enjoy this exciting flashback in time.

What was your 1st virtual reality experience like?

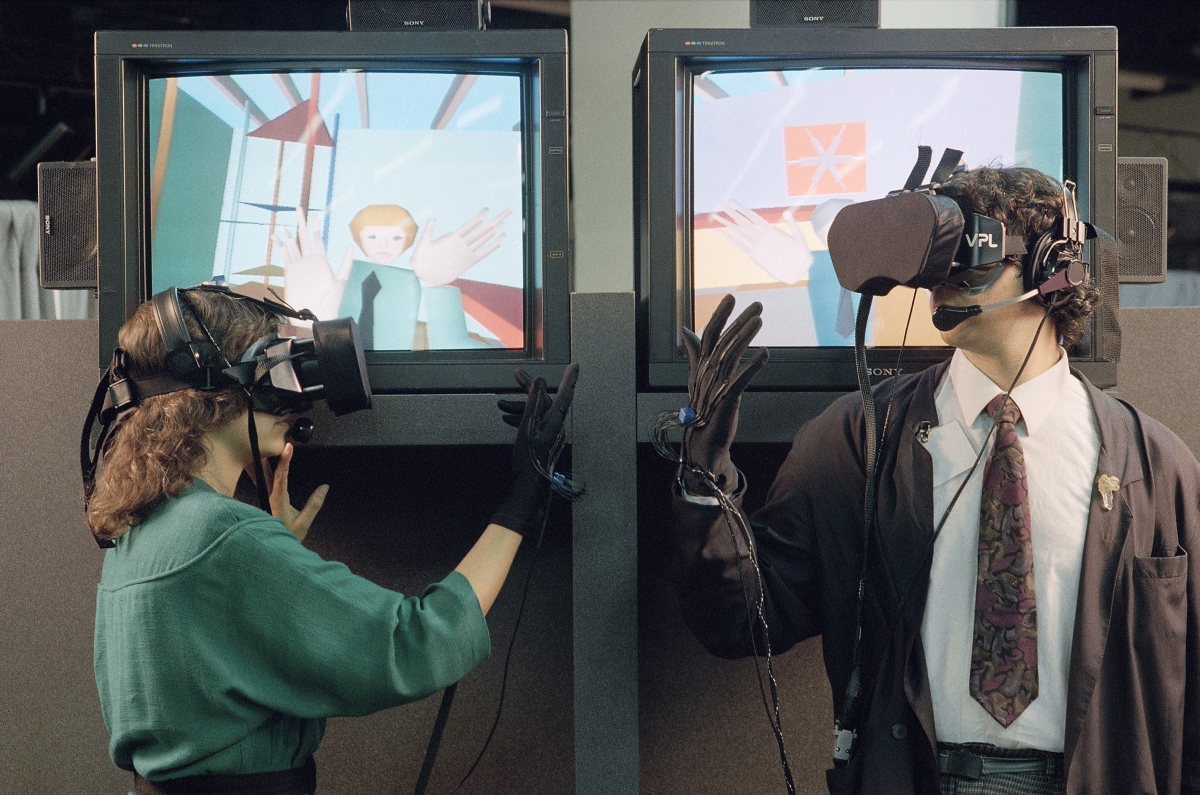

First experience… It’s hard to say, was it in Time Warner’s 2D The Palace, or my first time in VRML in 1995, maybe much later at Georgia Tech doing work with their VPL gloves and goggles.

After the dot.com crash I picked up a Master’s Degree from Georgia Tech. The gear there was used without any fanfare. It was even a bit of a joke was that this technology was brought out only to impress visiting dignitaries or raise grant money. With the heyday over, VR gear was simply a curious tool with unknown potential.

Describe the VR culture in the 90s and how art the scene influenced the medium.

For the arts there was a newness – an innocence in everything and it was (and still is) a time when every day you could do something that hadn’t quite been done before. Like a baby surrounded by adoring parents the simple act of moving around and bumping into things brought applause and speculation. There was a great deal of beautiful and interesting work.

Like a baby surrounded by adoring parents the simple act of moving around and bumping into things brought applause and speculation.”

Maybe the failure of virtual reality back then is hiding art’s influence – or – maybe art’s lack of influence on the virtual reality aided its failure. In fairness, the ideas of artists and academics don’t directly translate into engineering principles. The effort to bridge art and engineering through a language of design never really took root. In a field more hype than real, both sides pursued very different priorities.

![Timothy Leary [image source]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/07/timothy-leary1.jpg)

A good example of this divide emerges in 1990 when SIGGRAPH hosted a panel “Hip, Hype and Hope – The Three Faces of Virtual Worlds”. Among the speakers was philosopher / LSD enthusiast Timothy Leary. He talked about VR work by Brenda Laurel & Scott Fisher, Marshall McLuhan, of literacy as code, and maybe the virtual was already here. A great number of engineers just hated his point of view. So much so that they subtitled the very first IEEE-VR conference with a line that Timothy Leary was not Invited.

Unfortunately for the IEEE-VR, barring Leary did little to stem a flood of new, novel, and strange ideas. Baudrillaud’s Simulacra and Simulation was published in English in 1994. Marcos Novak was speaking of transarchitectures – liquid architectures in cyberspace. In sum, a wave of papers and theories rolled in from academics in every discipline imaginable. On the downside, hype was everywhere.

It’s also not that there weren’t collaborations and conversations. It’s just that artists and engineers spoke past each other. Artists got lost in the big human picture. The engineers were lost in the technical details. As a designer, I had a foot in both camps and could sense the disconnection, but I had my own struggles. My work became focused building virtual worlds based on poetry. Poems have always been great tools for breaking apart and understanding reality and virtual reality is no different.

In a sense it’s a take on game design and the relationship between story and space. After a while I began to see patterns emerge, structures and behaviors repeat themselves through-out my work. Sharing these ideas was, and still is difficult. There is no real language for discussing VR, so you can see the problem with usability principles gleaned from poems. In the end, doing poetry readings and musical performances with shapeshifting avatars in worlds that were edited like films drew people’s interest – but rarely any understanding. Thankfully there was a very small community of people who could code, model, and create innovative work. A lot of great conversations, projects, and sharing occurred.

What was the most interesting project you worked on?

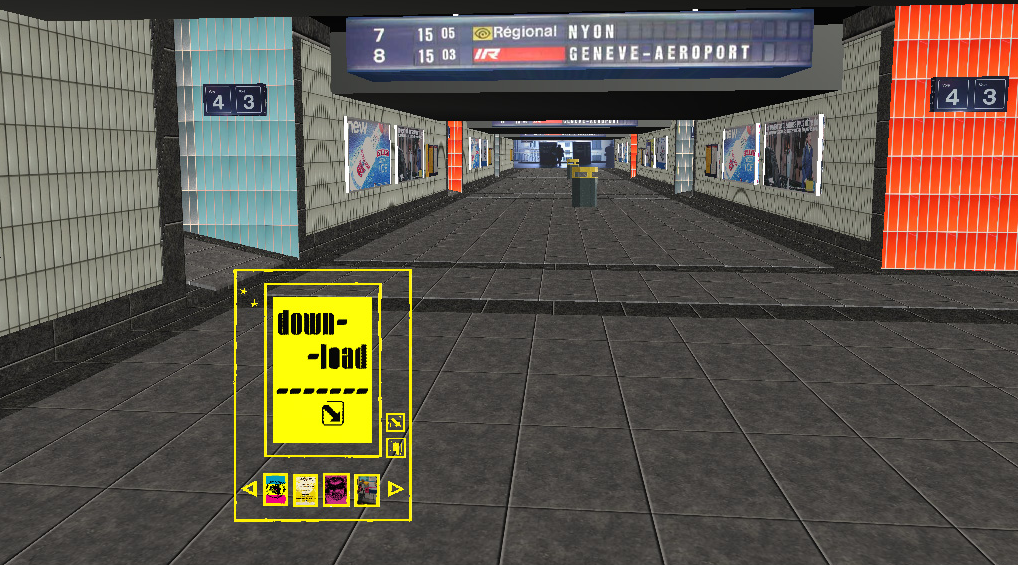

In 1999, fabric | ch created La Fabrique, an award winning online multiuser gallery built for “the 2nd World” of Canal+ (Le 2ème Monde in French. It was a beautiful gallery, an inspired architecture of abstract form relying on bent form, repetition, line work, and a hint of comedy to create a volume of space that felt like an artistic place. In hindsight, perhaps they went too far with the abstraction, but even so their work informs my 3D modeling practice today. The first opening was Digital Prosthesis and they invited some of the best web3D artists in the world to participate. A number of artists in my community got the call, and I was thrilled to be asked as well.

The thrill turned to shock somewhat quickly. Our total allotted file size for the art and images was 87k. Even in 1999, this was small. The second shock, which actually turned out to be a lot of fun was the size of our gallery spaces. We were given mobile home sized rooms. This scale might be fine for physical world artists but we working in VR were used building in multiple levels and/or instances in spaces that were as large as we wished. Given these limitations we did what artists have always done – we rebelled. Most of us used the limited size as both an inspiration as a target for our digital subterfuge.

Ars Electronica winner Andy Best, my friend and future employer, played to his strengths and further filled the small room by a placing a fiery digital monster in it and demanded the user negotiate passage past it. Squishing along the wall, while a large but only moderately unruly beast protests was perhaps Andy’s way of sharing his experience in developing for small the space with the visitor.

As for my rebellion, I simply added a floating red button to the center of my small room. The button, when pressed dissolved away fabric | ch’s entire art gallery in favor of a large underwater view of Zen pool. Users that pushed the red button shared the same space as others in the art gallery and could see and converse with other users, but they saw and travelled in a completely different looking interactive Zen space. This Zen space would flip back to the original gallery when the red button was pushed again. Before fabric | ch, I had been playing with an idea of users sharing a space and engaging each other – while seeing entirely different scenes based on a randomly assigned religion, gender, or race. Given the 87k limit, I shrugged and went Zen.

I was pretty proud of myself until I came upon my friend Cristiano Bianchi’s submission. Cristiano set forth a conceptually brilliant head high box with letters on the sides. Visitors would approach the box and put their virtual faces inside. Unknown to the user was the fact that Cristiano had also lessened the user’s avatar movement speed upon their face’s entry into the box. Slowed down, travel in the small box created the impression of a large space whose volume took time to traverse. Armed with the elegant simplicity of the idea, Cristiano coded the work to add ever more lettered boxes / spaces inside of each other and titled the work Infinite Babel.

There was one more issue for me alone among this group. It wasn’t a shock, and in fact it was normal. I could not see the finished art gallery. It was not because I couldn’t afford a ticket to Paris for the opening, but because I was a Mac web3D developer. At the time there was next to nothing for Apple developers and in this case the multiuser server was PC only. I would only see the full work live a decade later when I chaired the 1st Web3D Art and Design Retrospective, at the 15th Web3D conference co/located at SIGGRAPH 2010.

What was it like working with Apple computers back then?

This was the time when Apple was on the ropes. Steve Jobs had been fired and the company lacked direction. Apple didn’t support OpenGL back then and vendors shied away. Apple users had a couple of beta version plugins. The dominant PC plugin – Cosmoplayer had a huge memory leak and would crash often. New Tek 3D did release a Lightwave lite version called Inspire 3D which was advertised as a web 3D tool. It however shipped out with the wrong VRML export plugin and didn’t work at all. Eventually, I got through to the plugin developer who was pretty shocked to hear this mistake. I was pretty shocked that he was shocked… nobody at New Tek tried their finished web 3D product. They also never acknowledged – or fixed this problem. It was one of many lost opportunities.

![Screenshot of the SGI Cosmo Player [image source]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/07/cosmo-sgi1.jpg)

It wasn’t all bad, for my effort I got some minor fame as “THE Mac VR guy.” At the Mac Hack 99 conference I introduced myself as “Steve Guynup -Mac VR evangelist.” One guy just laughed and replied “I’m Tim – Mac OS evangelist. Do you want a job?” I said sure and we talked, but I didn’t think much of it, till I got a phone call a year later.

Unemployed and living with my girlfriend, a call from Cupertino was a nice surprise. Flown out, I toured campus and met with folks. The energy was great as Steve Jobs had just then returned. My interview was, however bad. My VR demo crashed (Cosmoplayer’s memory leak) and I disagreed with their Silicon Graphics strategy. The 3D world would be very different today had I gotten the job (sigh). On a happier note and soon after this, my friend Andy Best got his MeetFactory project funded by the government of Finland. I was off to Helsinki to work for him and for the first time to use a Windows PC.

In your opinion, how important is a polished VR project? Is it better to release a rough experience into the world or hold onto it until it is “perfected”?

In a bleeding edge domain like ours the issue is more about people understanding what you are doing, than polish. If you are offering a solution to a problem that people understand and hasn’t been solved, polish isn’t a big deal. If your work is just another game, polish matters a lot.

What does this mean?, well – if people don’t understand or care about the problem you are trying to solve, they won’t care about your solution. Innovation stops dead in its tracks and no amount of polish will get it moving.

Frankly there’s a lot of work that’s all polish and no substance. People are copying reality rather than designing it. After 25 years, I’m disappointed that much of our industry is still largely focused on more realism in rendering and behavior. It’s sort of an age old desire that tracks back through tv, cinema, photography, panoramas, the camera obscura, and even painting. Media & Film scholar Lev Mavovich once called VR at SIGGRAPH “Zeuxis and Parrhasius on an Industrial Scale”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trompe-l%27%C5%93il#History_in_painting

An early version of his thoughts on VR development, later written into the book The Language of New Media is here:

http://www.egs.edu/faculty/lev-manovich/articles/assembling-reality-myths- of-computer-graphics/

What does the future of VR look like to you?

Curiously, I really look to the past on this – are you up for the ultimate VR Flashback?

Early cinema was born in 1864 as a scientific investigation of the training of (and betting on) racehorses. It was seen as a medium of simulation. Realism was the goal. Early film developers worked hard to improve clarity, add color, sound, increase the frame rate, the length, and keep the film stock from catching fire.

Early film scholar Andre Bazin’s essay entitled “The Myth of Total Cinema” explains:

“The guiding myth, then, inspiring the invention of cinema, is the accomplishment of that which dominated in a more or less vague fashion all the techniques of the mechanical reproduction of reality in the nineteenth century, from photography to the phonograph, namely an integral realism, a recreation of the world in its own image, an image unburdened by the freedom of interpretation of the artist…”

What this means is that the language of cinema; jump cuts, close-ups, establishing shots, zooms, and flashbacks were completely unknown. Film was seen as a continuous stream of reality. At most it was cut into acts, like theatre. Editing the film, cutting and arranging bits and pieces to enhance the story was uncharted territory outside the realm of imagination for directors, producers, and the audience.

The following 1908 conversation between a producer and a young D.W. Griffith offers some insight into the challenge of editing reality:

“How can you tell a story, jumping about like that? The people won’t know what its’ about.”

“Well,” said Mr. Griffith, “Doesn’t Dickens write that way?”

“Yes, but that’s Dickens; that’s novel writing; that’s different.”

“Oh, not so much, these are picture stories; not so different.”

Flash forward to today and we get virtual reality addressing the same challenge of editing. I’m still waiting for a virtual D.W. Griffith to have this conversation with a critic:

“How can you understand a space that jumps about like that? The people won’t know what it’s about.”

“Well,” said Virtual Griffith, “Doesn’t Shigeru Miyamoto design that way?”

“Yes, but that’s Shigeru Miyamoto; that’s game design; that’s different.”

“Oh, not so much, these are still a mix of narrative and interaction; not so different.”

The true shape of virtual reality will start when designers borrow the freedom and flexibility of game design, but without the focus on immersing players in separate play driven worlds. In a sense, future VR will be an edited reality – but unlike film it will be altered to make it more useful and functional. In games we see this already, in World of Warcraft doors and often walls and railings are edited out.

There’s a lot of great history and deep theory here. The curious can find details and surprises (like the role of the Russian Socialist Revolution) here:

www.isovista.org/images/texts_theory/VirtualWorldsMythTotalCinema4.pdf

Many of the documents cited are here: http://www.isovista.org/index.php/database/theory

What projects are you working on now?

I teach game design online and just set up a small digital arts group, Isovista.org to support my students and recent graduates. It’s about nurturing art, innovation, education, in VR with the help of young designers and old professionals. Former students of mine Adam Walker, Jo Gibson, are helping out and many others are in touch.

![Isovista artist Adam Walker had his Cyberlith piece from the most recent virtual gallery displayed at the LACDA [image source]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/08/PrintInGallery_02_6ebb42521d9634e679ac44b9d3b211383.jpg)

Progress is a little mixed. We just shut down the multi-user gallery / classroom. It was in Unity 3D, which is both great and flawed. The gallery / classroom ideally would hold a large and constantly updated body of virtual art and/or educational presentations. Sadly game engines like Unity won’t allow scripts to be loaded on the fly, so our gallery and presentation space is pretty much hobbled at the start. Big downloads and occasional patches work for games, but not for us. Sadly, people with a videogame mindset don’t really see the problem. Since this isn’t something we can’t change, we’ll just dabble for a bit in Unity, X3DOM, and HMD’s

On the plus side, I got the data I needed on the impact of the Oculus Rift.

I also filed my first patent (provisional), and have more to come.

UploadVR’s “Flashback” series is an ongoing effort. We are looking for virtual reality pioneers who worked with VR in the 1990s and before. If you are one of those people or know someone who is, email Matthew Terndrup at terndrupm@gmail.com to arrange for an interview.