These opinions do not necessarily reflect those held by the editorial staff at UploadVR.

Virtual reality is about hit the mainstream, and it’s about to hit it hard. It is showing up everywhere – from being an integral part in large scale conferences to showing up at small, close knit meetups. Practically everywhere you look, VR is booting up to alter every industry it touches; but where did it all come from? Why is virtual reality proliferating into the market like never before?

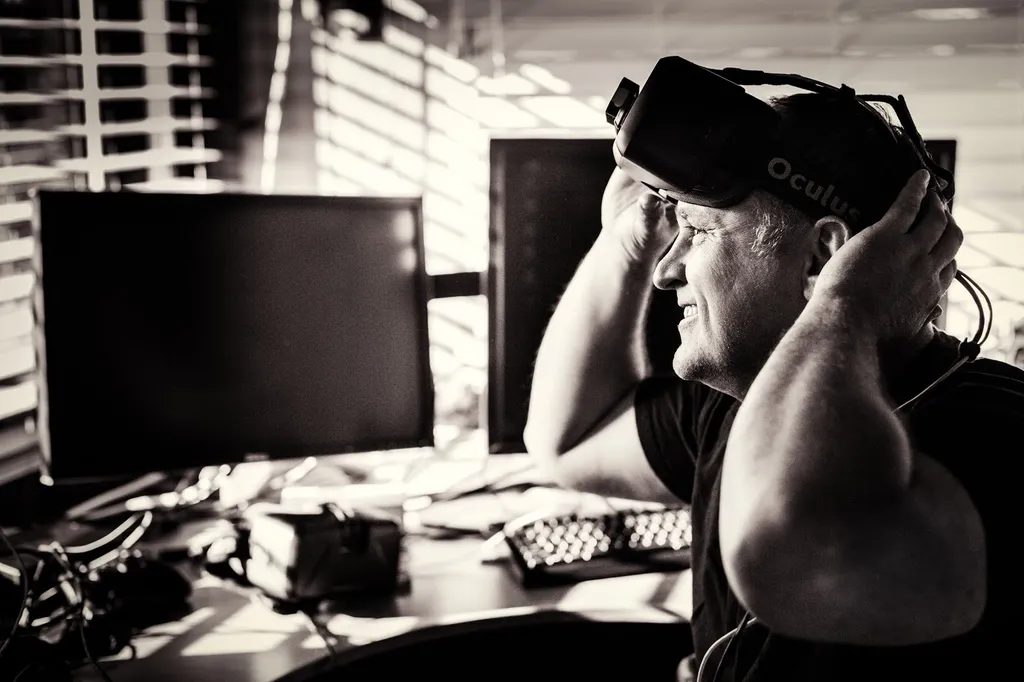

In a series of interviews and re-publications, we venture into the past to see where this exciting virtual reality ride began. Today, we interview Mike Roberts who witnessed the rise of VR firsthand in the 1990s. Roberts obtained a Ph.D. from London’s City University, where he worked in the area of parallel computing, visual programming, and graph theory. He has worked on a number of advanced virtual and augmented reality projects over the years and holds several patents related to the industry.

As the medium took off, Roberts came face to face with the wild experimentation that was happening at the time. Parties, events, and even Burning Man excursions hovered around the environment – pushing the innovation as far as it could go.

Through a several email communications, we asked Mike Roberts what the culture what it was like then and how it is similar/different from what is occurring now. So sit back, relax, and enjoy this exciting flashback in time.

So Mike, what was your first virtual reality experience like?

I’m originally from the UK, so my first experience of seeing real VR was sometime about 1990 with the Division stuff. The inception of VR in the UK was slightly behind the US, although my experience with computer graphics goes back further than this.

With some clever programming using both the main 6502 CPU and the 6522 IO processor on the BBC micro, it was possible to do very basic wireframe type graphics on microcomputers the early 80’s, as seen with games like Elite.

![Comparison between 1993 Division dVisor vs 2013 Oculus Rift [source]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/04/0-yC4FsdpgXXgu4VEb1.jpeg)

The UK was a hotbed of 3D in the late 80’s and early 90’s, which accounts for the large number of UK games programmers in circulation. 3D in general made it into the UK university curriculum a lot earlier than in the US; at least that has been my impression.

During my Ph.D. work in the late 80’s the Inmos guys like Steve Ghee had turned me onto reading William Gibson, and I saw code for Steve’s early work at Inmos on rendering pipelines using Transputer networks (the Transputer was an early British parallel computing chip).

![Transputer Inmos T800 [source]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/04/KL_inmos_IMST800_ES1.jpg)

At the research level, the state of the art at the UK research-level was systems with decent (16-64) numbers of Transputers, running Occam or C, and linked to Sun workstations (running the control software) and Inmos color graphics systems (for output). Some larger systems with thousands of processors were available in certain places, and a lot of core distributed systems work was done figuring out how to parallelize applications onto those systems.

You could do some real-time rendering and primitive ray tracing on the Transputer machines; people were doing a lot of more serious non-real-time 3D development like volumetric reconstruction, the type of stuff which was confined to the very high-end SGI machines in the US at the time. I don’t think the level of what we had (in the UK) at that time is well known, and a lot of this history is pre-web, so it’s not really available online in a very accessible form.

Steve Ghee gave me a bunch of sample T800 Transputers out the back door from Inmos to work with around that time, then went on to form Division and write a lot of their software. You can check out a great BBC video I found on YouTube, below, which shows the state of the Division demo as of about ’90.

I remember very distinctly hanging out with Steve and the crew drinking Genever (dutch gin) in Enchede, Holland at a Transputer User Group meeting in the late 80’s.

At that time I was working more in parallel and distributed computation (still an interest) with a side of graphics and in particular what became graph-based, node-based or flow programming – many of the ideas in that wider body of work associated with that formed the conceptual basis for a lot of the visual tools content tools you see in common use today, like the Maya Hypergraph and the flow-based programming in Max/MSP. By about 92-93, Intel and SGI had won, and the transputer systems were going into decline.

How did you get involved in the VR scene in the 90s?

I moved to California in early ’91 and spent some time working at a small startup called Mediashare, where I recreated a lot of my Ph.D. work on visual programming using graphs along with Art Whitten. We connected it to a multimedia engine based on-top of Smalltalk/C on the PC and Mediashare had quite an active group working on it for a while.

PC’s could not do 3D at that time – you needed an SGI or a specialist render box from Evans and Sutherland, or something of that sort. The Mediashare work became the basis of what became Kinetix (Autodesk) Hyperwire and was licensed to a couple of places, including Progress Software. I managed Progress’s software’s Graphical User Interface Technology group for a while and did work on the licensed code as well as some early real-time 3D node-based visualization code.

Around that time, I saw some of Ian McDowel‘s early Fakespace stuff at an event in San Francisco. That was the first stuff I saw from the US which I really liked, apart from Jaron Lanier‘s original stuff, which had a really human centric approach. I think that was at VERGE.

![The BOOM (Binocular Omni-Orientation Monitor) from Fakespace is a head-coupled stereoscopic display device [source]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/04/AndreOnBoom_lts1.jpg)

On the Fakespace stuff, the original monochrome “Boom” and later color versions – the fact that the orientation tracking was basically done using hardwired sensors with very low latency meant you got a great sense of immersion with their gear. Also the CRT screens in their stereo display were very high resolution for the time, 1280×1024 per eye, or something like that.

Fakespace could get away with nicer displays as the weight of the display was supported by the boom, as compared to the HMDs, which were limited in terms of their CRTs due to the display weight. That stuff was running off SGI machines at the time. Display weight is no longer a major issue with LCD displays.

![D’Cuckoo album cover [source]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/07/DCuckoo1.jpg)

SGI had a great VR evangelist who was concerned with connecting together a lot of the early wave of VR work, Linda Jacobson, who much later came and worked at PARC for a time (she also wrote an early VR book – “Garage Virtual Reality“). Linda was in a VR band called D’Cuckoo which used to do performances mainly in the bay area. I’ve always stored that concept of a VR band for later reference. I think it’s a good one.

I saw D’Cuckoo at CHI in I think ’92 or ’93, and started attending SIGGRAPH pretty much every year after that; from there I met a bunch of the the quieter more thoughtful SGI connected folks like Paul Haeberli, and Helen Cho, who together used to run Fiat Lux, a sort of alternative conference for graphics/hacker/art folks and were a great influence to be around.

Paul Haeberli still has some great programmer manifesto stuff up which is worth a read and right on the mark for the time. Then of course there was Morph’s outpost magazine, the Digital Be-In, and whole scenes associated with those folks. Deanan DaSilva was another SGI connected person at that time, but more concerned with CG in general than VR. I remember seeing the SGI racer and speedracer aluminum chassis at Deanan’s warehouse, which was the codename for the machines that became Octane and Octane2, really important machines in the history of computer graphics. At that time, SGI would comp you machines, if they thought you were cool enough.

Via Ian McFarland (who was working at Wired/HotWired just when they started and knew my interests), I got hooked up to the VRML folks and was on the VRML list pretty much from the inception. I saw the first Labyrinth demo, via Mark Pesce, Tony Parisi, and Owen Rowley from Autodesk.

Peter Kennard, who now lives in NY had a major role in getting that demo together in C++ based on the RenderMorphics Reality Lab rendering engine. I’ve known Peter for what now seems like a huge length of time, but his role in the production of the original Labyrinth demo has I think been a bit forgotten. He wrote the first version of Caligari True Space on the Amiga, as well.

![Tony Parisi, co-creator of VRLM [photo courtesy of Mike Roberts]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/07/foto_no_exif-61.jpg)

Flashback: Tony Parisi on Co-Creating the Virtual Reality Markup Language

RenderMorphics was another company formed from remnants of the UK graphics industry, by Doug Rabson (of FreeBSD fame), Servan Keondjian, and Kate Seekings.

Pretty much contiguous with the early VRML demos, RenderMorphics were acquired by Microsoft to form the basis of DirectX. Kate came to work in the US for MS, and was around in the scene in the 90’s, while the rest of the team stayed in London; she did some cool stuff like getting Douglas Adams to come to MS SIGGRAPH parties.

Continue reading on the next page: parties, Burning Man, meditation, psychedelics and more

Describe the culture of the time.

Lots of interesting people floating around in the 90’s were associated with VRML – Shel Kimen at SGI, Mark Pesce and Tony Parisi, Bruce Damer, and Karen Marcello (of Dorkbot/SRL fame), as well as many, many others, as distinct from the earlier wave of VR folks I have previously mentioned. More academic folks included Maribeth Back (now at FXPAL) and Elizabeth Churchill, who looked at the more social aspects of virtual spaces and wrote several books on the subject.

Many people in the web VR scene went to Burning Man at that time. Mark Pesce and friends ran a huge theme camp called Spiral Oasis, which is where most of the VRML related folks stayed. The first year I went, I didn’t camp with the Spiral – I was at another older camp called “Irrational Geographic” – no roads, you got your vehicle docked in by CB radio, and it was way out in the desert, well down the playa, not on the edge as it is now.

![Photo of Mark Pesce at Burning Man [source]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/04/Jon-Hanna_pesce_fire_134771.jpg)

![The Tibetan Tent from “Tent Tom” - previously used by the Beastie Boys on tour [courtesy of Mike Roberts]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/07/foto_no_exif.jpg)

Many of us interested in VR were never psychedelic users, but more interested in things like yoga and meditation. Ram Dass (who was one of the original people working at Harvard with Tim Leary) and who knows more about the differences in these approaches than I ever will, wrote a piece on this a while ago called “The Trap of High Experiences” which is interesting reading. Of course, it comes from the perspective of someone who is now a deeply spiritual person, so YMMV depending on your reaction to that sort of stuff.

![Another 90’s burning man photo [courtesy of Mike Roberts]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/07/foto_no_exif-31.jpg)

Psychedelics and Virtual Reality Have a Long Standing History – Here’s Why

In the early 90’s, 60’s icons like Timothy Leary were still around. I wasn’t that well connected with Tim and his crew, but younger guys like from the rave/consciousness scene like Jason Keehn knew those folks very well, having worked with Marilyn Ferguson (who wrote “The Aquarian Conspiracy”). Jason also worked with us at UrStudios for a while, writing about GEL.

By ‘96, Tim Leary was gone, and the influx of money into the .com bubble had really started in earnest; I see this time as the end of the earlier era. Bruce Damer has some of Tim’s material, including his record collection and papers, stored at his DigiBarn computer museum, as well as other stuff from Terence McKenna.

Some of the more esoteric private events in LA would bring together folks from the older times like Francis Jeffrey (John Lilly’s biographer), Jerry Pournelle (Byte), random indian gurus, ravers, people working on human-dolphin communications, astronomy/music folks like Fiorella Terrensi, in contact with various Hollywood and VR folks. I think it’s important to realize that these folks were not in the main the folks really driving computer graphics forwards – that was a the SIGGRAPH community. But various folks within that wider umbrella did spend time with some of these counter cultural icons and talked about stuff. Leary in particular was very interested in VR.

![90’s party scene - gallery in LA [courtesy of Mike Roberts]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/07/foto_no_exif-21.jpg)

Friends of Leary like Brummbaer were also around and still are. Brummbaer is a great psychedelic artist, having worked with Zappa and Tangerine Dream in the 60’s and subsequently moved on to doing computer art that defined much of the look we think about as 90’s VR via his work on the Cyberspace sections of the Johnny Mnemonic film, Mind’s Eye videos, SIGGRAPH shorts, etc. Some of that stuff looks a bit dated now, but it was a huge reference point at the time.

Coco Conn’s crowd in Los Feliz was a different set – everyone from Danny Hillis (of Connection Machine and Long Now fame) though to Mark Pesce and John Perry Barlow (Grateful Dead/EFF) showed up there. At that time it was totally unclear where the digital pipes would connect up. LA, having the entertainment connection, was one likely spot.

Another parallel scene in the bay area revolved around Mondo 2000 and the Wired folks and was more Extropian in nature.

For my own part, I was lucky enough to meet some of the folks involved in bringing over yoga from India in the 70’s, as well as some amazing modern/jazz dance people, who got me thinking deeply about immediacy in interaction, and what interactions feel like as an experience. Brenda Laurel’s book “Computers as Theatre” is an interesting work in that vein.

![Fire Dancing occassionaly flowed around the VR culture in 1990s [courtesy of Mike Roberts]](https://www.uploadvr.com/content/images/2015/07/foto_no_exif-41.jpg)

What advice would you give to those creating VR content now?

“I’d like people to get back to having a focus on doing amazing things, and less on making huge amounts of money.”

VR is a part-time interest for me at present (my main work over the past 4 or so years at PARC has been on the hard problem of understanding and representing user context with semantic models, so that it can be understood by AI systems, or used in augmentation – and also working with startups and organizations licensing technology from PARC). So, I get to approach thinking about AR/VR currently in a way unfettered by commercial concerns, as that’s not where my main income stream is coming from. So, please take what I say as coming from that perspective.

One initial comment I would have to make is to be really wary of where your advise is coming from. Now that VR is trendy again I see people who have never really worked with it jumping on the bandwagon and making all sorts of odd statements, when they really don’t have sufficient experience with any sort of related technology to be making such expositions. Maybe I’m just being a grumpy old guy here, but you get the picture.

I like to think about VR as a new art-form, a new medium, distinct from game-type entertainment, obviously, but that is not an uncommon thought. Traditionally, the arts are where people really get their connection into the physical world. In acoustic music, for example, you are working directly with resonating objects. In traditional art-based interaction, we have many thousands of years of refinement in process and technique. With traditional static visual arts such as sculpture, painting and drawing, people explore representation as well as physical processes like the properties of particular refractive materials.

There is a tendency for production in digital media to be very annoying, process wise, to people who are more experienced with traditional art – there is a lack of immediacy there, and a tweakiness to the specification of things, which is deeply annoying to people who like to work in the physical world and have highly refined motor skills. Many current CG tools I regard as being like this, and they tend to get used in the modern production pipeline to box people into doing specialist tasks. I knew someone in LA who spent much of her life at that time lighting the inside of pig’s mouths with a modelling package, and she hated it, being an accomplished artist capable of doing much more.

To define a new medium, you can’t ignore this stuff, you have to crank down on making things highly interactive and work with them at a very fine level. For example, in sensors, at the moment, 60Hz is the standard for consumer level camera based trackers. That’s no-where near fast enough. When you run that sort of stuff through the latency we have with the current Web VR stack, you just get something lacking in interaction fidelity. Maa Berriet is in my opinion one of the people who is working currently who really understands and relates to this.

Same thing for graphics. I don’t want 4k graphics, I want something at or above 10k per eye, at 120Hz or above. No machine made is fast enough to do that currently, with a decent scene. I like the current Oculus emphasis on high performance, but I’m a bit worried about the prospect that they are creating a walled garden in which only approved content from their market-place goes onto their device, something which is polar opposite to what everyone though Palmer’s original goal was when he did the kick starter. Tony Parisi I know distinctly feels this worry too. But we’ve got other nice competitive headsets coming out soon, like the Star VR unit, so hopefully manufacturers will not want to lock people in like this.

On the web-side, to get specific, not having real real threads in JavaScript and having to rely on web workers is just a huge limitation. Similarly, proper geometry loading from something other than text. Likewise, for sound, if you can’t hear the difference between an .mp3 and a 24 bit lossless sample, your audio system and/or ears are seriously deficient. And of course lag/stall, obviously.

On the marketplace side, I just really dislike the idea of users not being able to make and publish content for themselves in some sort of really deep way, and to some extent I just see these walled marketplaces and being a reaction against viruses, griefing, and the people/organizations who support this sort of thing. These types of problem have been around for a long time and any viable multi-user expressive system is going to have to bump up against this problem again and again. It’s like a continuous friction which just makes freedom of speech and expressiveness in the digital environment much more difficult, and I really wish it didn’t exist. I’ve thought a lot about how to deal with this.

In order to understand the fidelity issues, I think you need to train your body and senses in some way. For example, learn to play a musical instrument, do Zen, Kendo, whatever, but get some deeper sense of connection with things so you can recognize the difference when you don’t have it. Jaron I think understands these sorts of issues really well and is an extremely accomplished musician, bringing that understanding to his previous work and current writing. If you don’t do something like this, I believe you are at grave risk creating something dumbed down in comparison to the potential which exists. Maybe for now, you accept you are doing glitch, but at least try and get some sort of handle on what the parameters of that are.

Thinking again about the software side and going back to the point about people getting locked into process, I think there needs to be thought given to making your own tools, as opposed to using what comes prepackaged from Unity or wherever. In Japan, there is the sense of Monozukuri – literally “the art of making things” , to look on the process and making of an artifact or tool itself as an art-form. So I think we need to look beyond mere content creation and make the process of making VR experiences with tools itself a beautiful experience. Most of the tools we have at present are not art tools, they are tools for making experiences is a specific genre – games, or derivatives of movie type CG tools, etc.. I think we are not at the point where we really understand the process of VR creation yet, either, in any sort of formal sense. There is the whole domain of how proceduralism and generative art links to VR to be worked out, for example.

Once you start thinking about things in the way I’ve laid out above, I think the money becomes less important. I think that’s one of the main differences I see today with the 90’s – I’d like people to get back to having a focus on doing amazing things, and less on making huge amounts of money.