Ghost Giant is, as we made clear in our full review, a remarkable game that handles the subject of depression with skill and care. It’s not a game that constantly discusses depression. Indeed, it initially appears to be little more than a standard cutesy VR adventure; and even after the struggles of the main character’s mother become apparent, jokes are made and most characters remain oblivious to her situation.

This nuance is precisely why it works so well.

The initial Ghost Giant prototype was set in a small American town, and the main character, Louis – at this point named Ned, and a bat rather than a cat – was being bullied. A radical change in direction (and setting) quickly took place once a writer was on board, however.

Sara Elfgren, an established author and screenwriter making her videogame debut with the Ghost Giant script, explains where the idea came from. “I read this article about children who grew up with addicts as parents, and how they very often have to take on responsibility from a very early age,” Elfgren says. “I was very moved by one of the stories in that article about a young boy who was taking care of his siblings when he was just a very small child himself. That made me think about Ghost Giant […] I got thinking what the story could be, and what he was hiding”.

The setting meanwhile changed from a small American town to a French one, as the color scheme in place reminded Elfgren of Les Parapluies de Cherbourg [The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg], a 1960s musical.

“I thought, when we tried putting together a mood board of French picturesque small towns, and old cars and clothing, it just really clicked better with the story,” says Olov Redmalm, Creative Director and Art Director. “A bit more melancholy, calm, cute setting. The colors got a little bit warmer, and we suddenly had more countryside instead of just rowdy streets”.

Whereas the few mainstream games that tackle mental illness, such as Hellblade, tend to put the player in the shoes of the person with the illness, Ghost Giant offers an outside perspective. If you are living, or ever have lived, with a loved one with severe depression, there are several story beats that will slam into your emotions with immense force.

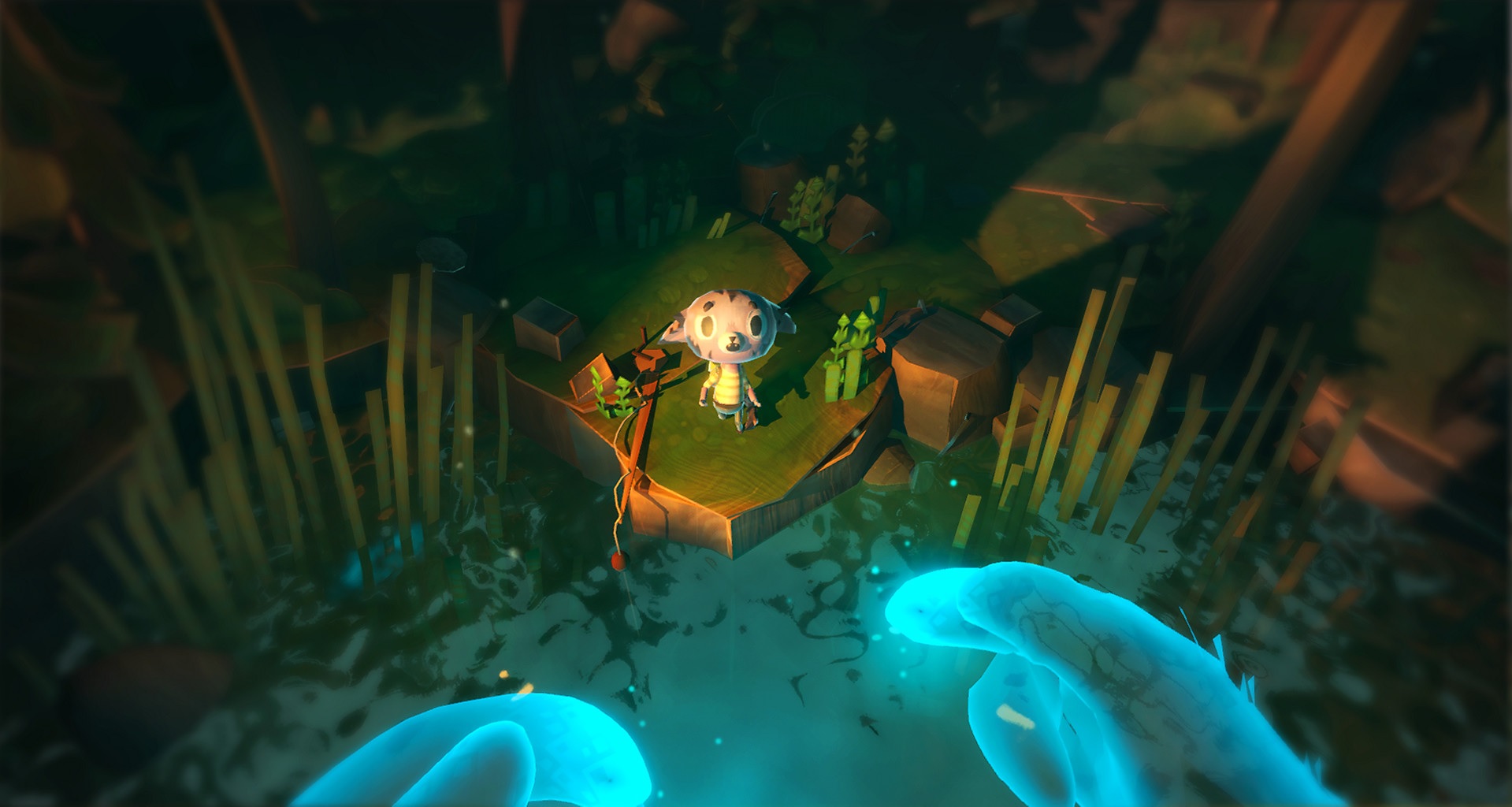

When away from home, Louis will hide his feelings from the world. At home, his best efforts to cheer his mother are thwarted. She upsets him not through malice, and certainly not through intention — but through indifference and fatigue. As is so crushingly common in the real world, Louis blames himself for her condition. The moment he vocalizes this is a heartbreaking one. Reach out your virtual hands to comfort him, if you like; it won’t help.

While Louis’ mother isn’t on screen for most of the game, and you do not control or interact with her, her character is given depth. In one memorable scene, the player is treated to household pictures that recall happier times.

“I fleshed out Pauline [the mother] as a character in my mind, and also in the character bible, so I knew exactly what she was like when she was not depressed,” explains Elfgren. “I think that’s also very important, if you write a depressed character. We knew the story of her when she was not depressed too, so she is this whole character. She’s not just her depression, and I think that’s very important”.

It’s not always a cheery game, then, but it is precisely for this reason that it can do some good. Hopefully, there will be people who play this game and realize that they’re not alone, or they’re not to blame, or that maybe things can improve if they reach out and ask for help from others. It even struck a chord with the development team, something Redmalm is keen to discuss.

“The team immediately clicked with the script, and everyone was very, very enthusiastic about telling this story,” Redmalm recalls. “There were many occasions where we would stand together and look at an animation. I remember one occasion specifically where we were talking about the animation of Pauline in bed, and we were discussing how she was supposed to lie. Like, is she facing Louis, or is she facing the wall, and how would I lie, and suddenly we’re inadvertently beginning to talk about our own experiences without talking about it directly. It was actually kind of beautiful […] it really helped the team spirit to have this topic that everybody felt very passionate about, and wanted to do justice, and really give it our best and treat it with respect”.

“We didn’t want to treat it as a cheap twist, you know,” agrees Elfgren. “That was very important for all of us. And also, I consulted a child psychologist when I wrote it. I told her the story, and I read her the dialogue in the scenes that concerned Louis and his mother. I had done a lot of research on my own, and I had my own experiences and stories that I’d been told; but I felt it was important to get a professional’s view on it as well. She said that it was very accurate. I mean, every story of depression and mental illness is different, of course — there is no ‘This is the way it is’ – but she felt that it was an accurate portrayal”.

An accurate portrayal it is, regardless of the animal characters and toy-like environments. The game ends on a positive note, without simplifying the issue or pretending that there’s a magical salve for depression. Overall it is, as Elfgren tells me she felt at the time, an important story to tell. She goes on to describe Ghost Giant as it truly is. A wonderful, beautiful, and perfectly fitting description; a fairytale.

“This is not a children’s game, but of course young people and children can play it. But I think that in Sweden it’s not taboo to handle heavier subjects [in family stories]. And also I think that if a young person plays Ghost Giant and is not aware of depression, for example, I think they probably accept the story on their terms. With their experiences. Whereas an adult, or somebody who has dealt with these things, will experience it in a different way. That’s the power of the fairytale, I think. […] You’re not shut out if you don’t understand everything, you just understand it differently”.