Half-Life: Alyx features polished physics interactions that may represent one of Valve’s not-so-secret weapons.

Physics-based interactions have become an expected feature of major VR titles after games such as Boneworks and The Walking Dead Saints & Sinners. Virtual environments are now becoming more interactive, leveraging the unique gameplay capabilities that VR with positionally tracked controllers enables. For more on why these mechanics are compelling and represent the future of VR, I recommend reading Jamie’s article Getting To Grips: Boneworks & The Walking Dead Prove The Future Of VR Gaming Is In Physics And Interaction.

While Half-Life: Alyx avoids melee combat, the project showcases the same kind of compelling physics interactions as the Walking Dead and Boneworks. In particular, though, we’ve noted a general smoothness to the handling of multiple objects in the new Half-Life game that puts a spotlight on Valve’s forthcoming Source 2 toolset. That smoothness may point to a related Valve project in the works for at least 8 years: a custom, in-house physics engine called Rubikon, and that engine could point to Valve’s next steps in VR.

Rubikon: A Next Gen Physics Engine

Games are built using game engines, but the majority of game engines do not handle physics internally. Instead this is handed off to a third party physics engine which is often pre-integrated.

Half-Life 2 and its ‘episodes’ used Valve’s new (at the time in 2004) Source game engine. But while the game represented a major leap forward in the implementation of physics, the physics engine used was a third party solution called Havok (which over the next decade became the most popular physics middleware).

Half-Life: Alyx uses Source 2, the successor to Source first used in Dota 2, also used in SteamVR Home and the Robot Repair scene in The Lab. Source 2 is a Vulkan-based engine which allows for the impressive visuals seen in Alyx. But the Rubikon physics engine built into Source 2 is even more interesting for VR.

Not much is yet known about Rubikon. It was first unveiled at GDC 2014, six years ago, during a talk titled ‘Physics for Game Programmers’. In this talk Valve’s Sergiy Migdalskiy explains that Rubikon has been in development since 2012, and serves as the replacement for Havok.

Senior Software Engineer Dirk Gregorius’ LinkedIn profile claims he is the author of Rubikon. Gregorius has also given physics talks at GDC, but these talks are more about technical details than product overviews.

A custom physics engine using best practices and state of the art algorithms could be one of Valve’s key offerings in the next generation of game development, and Half-Life: Alyx appears to be the first major showcase of this.

The State Of Physics In Unity & Unreal

Most VR games, including Boneworks, are built using the Unity game engine. Unity is currently going through a slow, gradual full stack overhaul of its major components. There are actually three major physics engines at the time of writing: NVIDIA’s PhysX, ‘Unity Physics’, and Havok physics.

PhysX has been used in Unity for over a decade now, and is used in Boneworks (it was the only option available when Boneworks development began).

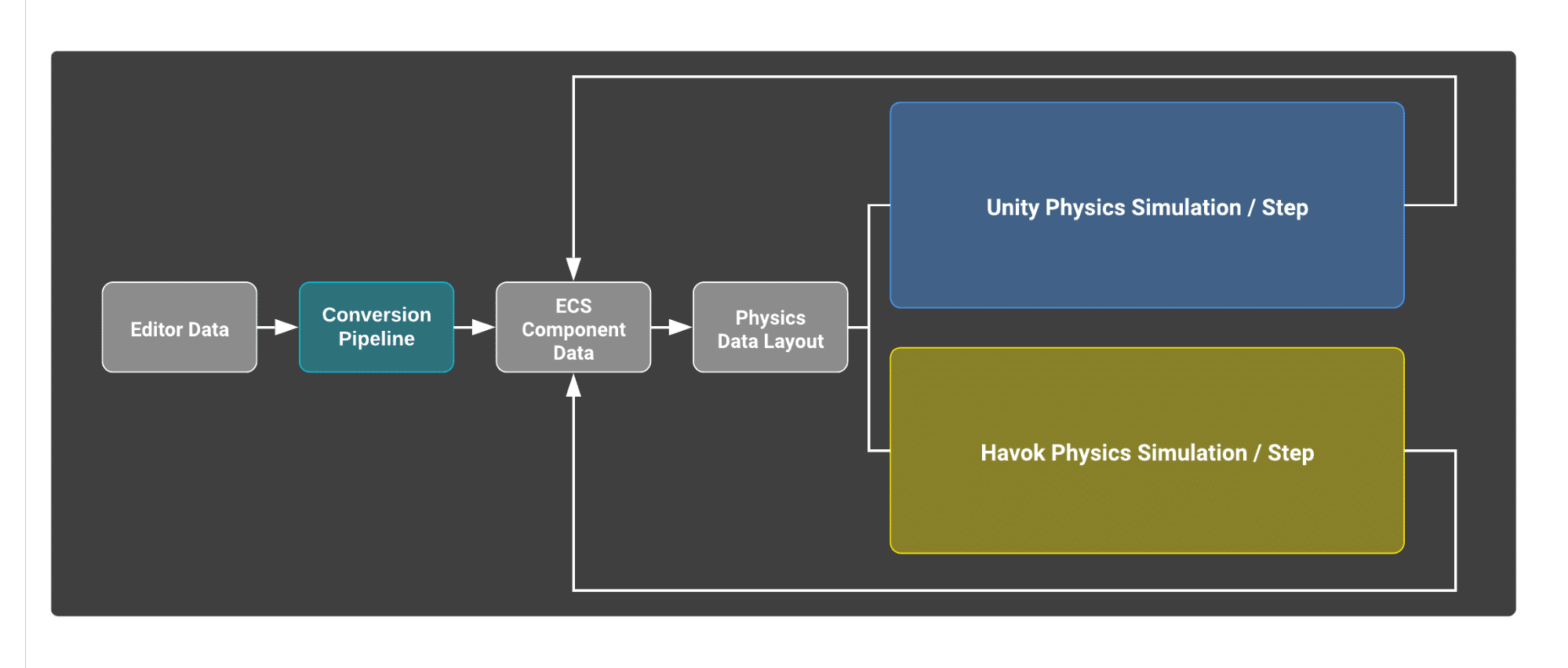

‘Unity Physics’ and Havok were announced quite recently, in March 2019, and are still in preview. Both leverage leverage Unity’s new DOTS (Data Oriented Tech Stack) architecture. DOTS requires developers to program their games very differently than before, but enables significantly more entities to be simulated each frame. DOTS is also still in preview.

‘Unity Physics’ is also based on Havok, and is data compatible (developers can toggle between the two). Unity Physics trades off performance for supporting network rollback for multiplayer titles. Havok is the highest performance option but more suited for singleplayer.

DOTS is planned to be fully released this year. Epic is also working on a new physics engine for Unreal Engine, an in-house solution called Chaos. Like Unity’s DOTS, it will allow for higher performance and higher fidelity than PhysX (what Unreal also currently uses). But it’s also still in Beta, not yet ready for use in major projects.

The timelines for these engines suggests that studios using Unity & Unreal may need to take some time before they adopt these technologies because they risk losing time due to significant changes in the tools during development. So how will DOTS Havok & Epic’s Chaos stack up against Rubikon when they are fully released? We can’t answer that yet. But a company like Valve would likely not have spent much of the last decade building and improving a replacement for Havok without benefits in doing so. Developing a physics engine is no minor undertaking.

Half-Life: Alyx appears to be the first showing of an investment in physics that Valve has been making for most of the past decade, and until Unity & Unreal’s next gen physics systems are ready for developers to use, Source 2 games may end up becoming showcases for the types of physics so many are learning to love in Half-Life: Alyx.