Before my demo at Google I/O, Google’s head of VR Clay Bavor outlined a series of caveats and expectations for what I was about to experience.

First, he said, I was going to use a generation older hardware from internal prototypes that likely would be improved upon in practically every way before its release as a reference design to developers and eventually to consumers (Google hopes at least HTC can achieve consumer release in 2017 with its first standalone headset). Second, latency on this hardware was said to be under 30 milliseconds but would be improved to under 20 milliseconds — a critical threshold for comfort — by the time the system reaches broader deployment. The system was also running an older display at 75 frames per second. Bavor declined to comment as to the frame rate of the finished hardware.

Yet, for 120 seconds in one demo on a rug-sized space large enough for two to three steps in any direction I became one of the first journalists in the world to try WorldSense — an evolution of Google’s Tango efforts and an answer to the inside-out tracking technology Microsoft developed for its $3,000 HoloLens and then adapted for use in a series of far less expensive VR headsets starting with one from Acer. Facebook, too, is working hard on inside-out technology and showed its Santa Cruz prototype last year using this more convenient approach to VR headset design. Intel is working on it as well, and says it will have devices out by the end of the year.

WorldSense

The demo, according to Google, would reset after each journalist so the hardware would see the room fresh each time after each person donned the headset. WorldSense is designed to intelligently look for anchors in the real world and grow smarter over time — discarding parts that might have moved while gathering more detailed information about the world around the person wearing the headset. I saw this immediately as I started to move around in VR — with tracking initially stuttering just slightly and then within 10 seconds or so turning rock solid with full freedom of movement in all directions. Though, of course, I was limited to my rug — if I moved outside the world would dim into blackness.

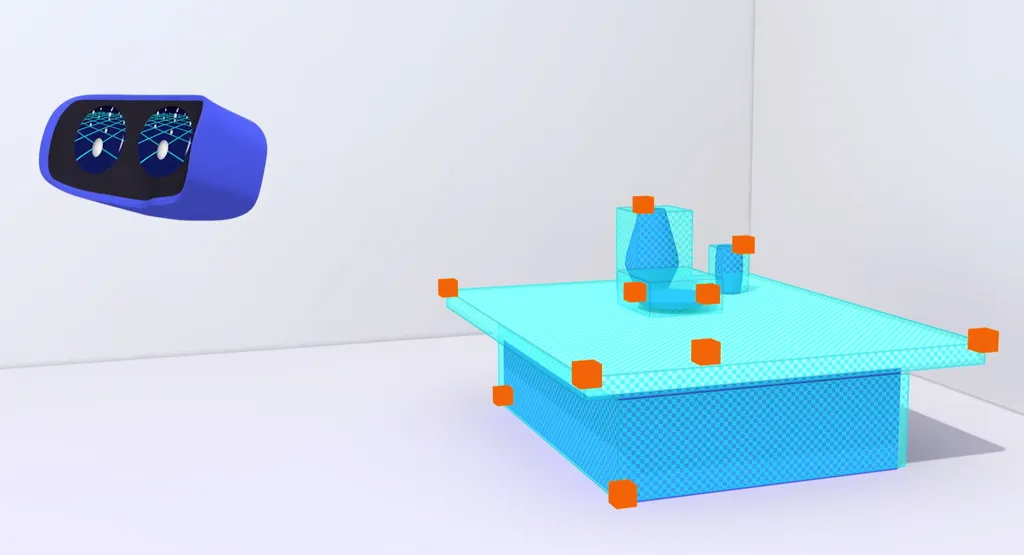

I covered both the outward facing cameras and Google’s tracking technology continued to track my head movements in every direction accurately for about one second. Then it reverted to the kind of 3DOF head tracking seen with current Daydream and Gear VR headsets. After removing my hands and letting the pair of forward-facing cameras see the world again I also got down on the ground facing toward the ceiling, looked to my sides on the floor, and noticed no jumps in tracking as I got up from the floor.

The scene was a simple underwater one with turtles and jellyfish floating around me. I was disappointed to note that there were no objects that seemed to move within my volume of movement freedom. In other words, the jellyfish and turtles seemed to stay just out of reach, so I couldn’t gauge whether an object that seems to float in the center of my virtual space would seem to drift out of place over time.

The space afforded for movement freedom was greater than I’ve experienced in Acer’s Microsoft-powered headsets but smaller than a carefully lit and arranged room shown by Facebook’s Oculus last year. Only Intel’s demo at CES this year placed objects in the center of the room allowing me to gauge the drift of virtual objects.

According to Google, the company isn’t expecting to initially offer active detection and warning about cats or kids that enter your space. It will, however, offer an established volume in which you can move around with complete freedom and then warn you if you move outside.

Bottom Line

I left my demo impressed by Google’s progress with inside-out tracking for VR headsets, but scratching my head about the market Google hopes to serve with these initial standalone systems.

Google’s guidance is that when the WorldSense standalone systems arrive — supposedly this year from at least HTC — is that they are likely best used seated and standing in place. This sets the systems up as an improvement on Google’s Daydream platform featuring better immersion, but still a small step on a long path that will still take years to realize. It is a lot to ask someone to invest $400-$800 in a dedicated headset that is a marginal improvement upon a phone-powered headset without the benefits of a fully featured phone you can use separate from VR. It is unclear what market Google hopes to serve with these initial standalones.

I was not able to see the headset paired with the Daydream controller and this is a critical component that will define which market segment this first generation of standalone headsets will target. Many developers should find their apps built for Daydream will extend to these standalone headsets without too much modification. However, developers will have to figure out how to design around the fact that you cannot naturally reach out with your arm using a Daydream controller to interact with an object.

Educational or exploratory apps like Google Earth could conceivably work incredibly well with these types of standalone headsets from HTC and Lenovo, but leading apps like Tilt Brush and Job Simulator will likely need to wait until some time after 2017 before a standalone system powered by Google’s technology is able to offer the kind of experience we’ve come to know with something like an HTC Vive.