One year ago HTC Vive started arriving for buyers. It was $200 more expensive than its chief competition, the Oculus Rift, but the headset also did a lot more than the initial PC-powered headset from Facebook when it first released.

At the heart of Vive’s leap is a fundamentally different tracking technology which involves mounting little boxes to the walls just like you would speakers. These boxes just need to be plugged into power to track objects with pinpoint accuracy across a 5 meter-wide space — for roomscale, it’s much cleaner than the Rift’s multiple USB cords running back to the PC. These boxes disappear when wearing the headset and you find yourself with the freedom to walk several steps around a virtual world and use your hands to interact with it.

The tracking innovation made by Bellevue-based Valve Software and manufactured by HTC gave the Vive headset and controllers a six month headstart on Facebook’s VR team in the roomscale race. In some ways this lead was actually quite a bit longer, because HTC and Valve started telegraphing to developers pretty early on that this was the plan. Oculus, however, went to market without hand controllers readied, supporting a single sensor for a forward-facing experience.

“We told [developers] there were going to be two sensors in the box and two controllers in the box,” said Dan O’Brien, HTC Vive’s top leader in the America’s. “That removed the guesswork for them.”

What’s more, HTC and Valve put these free developer kits in the hands of skilled creators spread across the globe. Oculus gets credit for kickstarting interest in VR with its 2012 crowdfunding campaign, and Facebook gets credit for convincing investors the technology was a sound bet for the future with its $2 billion acquisition, but these free Vive kits accelerated VR development in fundamental ways.

The Gift of Freedom

Vive kits were given free to programmers, artists, and eventually press. This giveaway of advanced technology helped accelerate VR development into a new phase with greater freedom.

The Vive Pre and the kits that came before it allowed for the development of groundbreaking software seen in apps like Job Simulator and The Gallery. Compared with Rift, Vive was offered with fewer restrictions imposed on developers for a longer length of time. Vive creators could share their discoveries with others for much of 2016 while Oculus largely locked down discussion of the Touch controllers for much of the year.

“We didn’t want to put any controls on people,” O’Brien said.

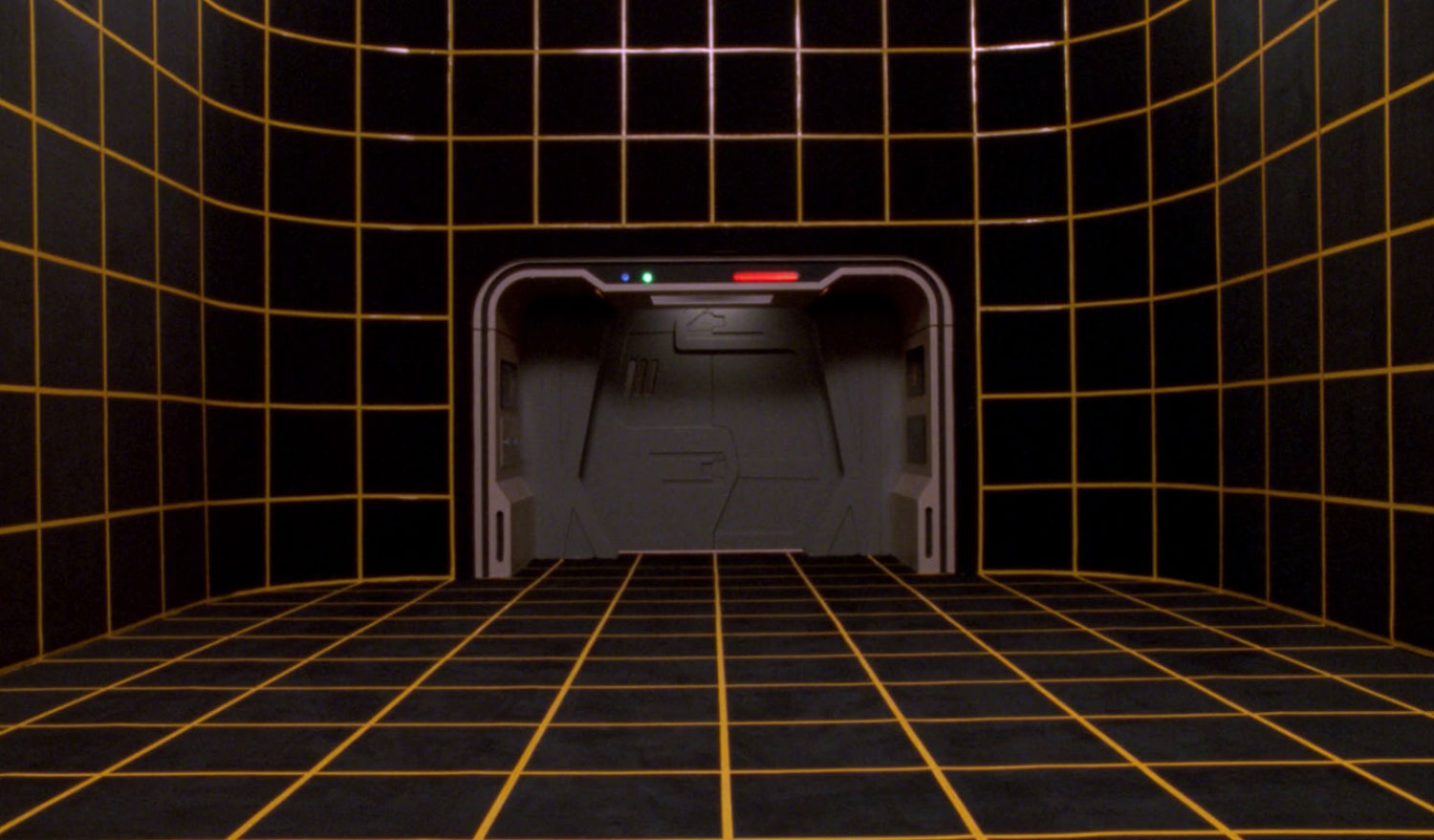

While Oculus was advising developers to focus on forward-facing VR experiences and shipping a Rift and gamepad to consumers, Valve and HTC were shipping this:

This moment taken from Valve’s launch video published one year ago captures the essence of Vive’s contribution to VR. It is a piece of marketing, sure, but in one second it shows the quality of the tracking, the freedom it allows, and the use of mixed reality to show exactly what a person is experiencing.

Given the Rift’s required USB cords to connect the sensors, it is reasonable for Oculus to assume most people will set up two of these sensors at either end of a desk to experience VR with Touch in a 180-degree configuration. So this simple act of turning around repeated in a Rift could easily block a controller from the view of the sensors, causing your hand to fly off or disappear. It is so natural as a human to move around as a way of exploring and interacting with the world around you, but in lots of Rift software the developers have carefully designed their worlds to keep visitors from wanting to do it. Oculus assumes that with its recent price drop to $600 for a Rift, two sensors and two controllers, that new buyers drawn in now will actually have less space allotted for VR than the earliest adopters. This might well be true but I think it glosses over something fundamental I believe about VR’s adoption long-term — something Vive got right from the get-go.

The Future of VR

Star Trek’s Holodeck was imagined in the late ’80s as a big room where you could run any simulation to practice for the real world, or indulge in any fantasy you desired as a way to escape the long monotonous trips between star systems. It was figured to trick your mind into making imperceptible corrections to the direction you were walking, turning a straight path into a curve so that you never reached the edges of the room. This is how a room turned into a vast forest in Star Trek: The Next Generation’s first episode.

It will be a long long time before something as real as the Holodeck exists, but I see the premise of imperceptibly tricking your brain so you don’t notice the edges of a virtual world as a fundamental guide to the technology’s future. The saying goes that you can fool some of the people some of the time, but not all the people all of the time. This is relevant for VR because even in some of the most expertly crafted virtual worlds like Job Simulator, where you stand in a cubicle or behind a convenience store counter playfully “jobbing”, occasionally people will remember the counter isn’t real and the walls of the cubicle can be walked through. Curiosity drives us. In well-made software, asking “What happens if?” rewards people. With limited hardware, though, asking that question too often results in a stern reminder that you’re in VR and not as free as you want to be in there. Wearing a Vive with its default setup, you’ll hit a blue wall if you go too far. In a Rift with its default setup, you might turn around and lose your hands.

Smart software design can make some people in a Rift not turn around, but developers can only do what the hardware allows them to do and people are curious animals ready to test their limits. The more freedom enabled by the hardware, the more times “What happens if?” will be answered by something exciting, and HTC enabled that greater freedom first.

The Future of Vive

Vive is readying for the next phase of hardware efforts as the headset is poised to become part of a much larger ecosystem of VR hardware with the $100 Vive Tracker shipping to developers.

Of its countless potential uses, these Trackers could be used for full body tracking. Instead of a soccer game like Headmaster that cleverly uses VR’s limitations to give you a game in which you can headbutt balls into the goal, a Tracker clipped to your shoe could enable a realistic soccer simulator that lets you actually kick the ball into the goal.

Guns, boxing gloves, baseball bats, cameras, firehoses and a whole lot more can be brought into a virtual world to make an experience more convincing. When combined with the upcoming deluxe audio strap, Vive aims to continue a lead it established in 2016 that expands upon the ecosystem that’s already there.