Mark Bolas is one of the pillars of the VR industry. Having worked with virtual reality since the late 80’s, and has probably spent more time in VR than you and everyone you know combined. Mark’s expertise has been instrumental in guiding visionaries like Palmer Luckey and Nonny de la Peña, and has helped to shape the modern industry. Mark currently works as an associate professor at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, and director of the Mixed Reality Lab and Studio at USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies.

I had a chance to catch up with Mark at Sundance last week, and spoke with him about what VR’s effect on the narrative, what this new medium is really about, and how VR has the power to effect us. Mark had some interesting thoughts on the matter including an intriguing counter to the common “empathy machine” description of VR.

——-

WILL: Mark, you’ve had quite an instrumental role in the development of virtual reality over the last decade, or two decades. Can you maybe sort of describe your history in the space?

MARK: Sure. I had the really good fortune to work in the NASA Ames view project, which was started and run by Scott Fisher, and in that project that was oh, 1989, I had access to what is effectively what people think of now modern VR. So there was a mounted display with a 120 degree field of view. It had positional tracking, angular tracking. We had gloves that we could put on our hands to see virtual hands, and it also had stereo audio that was convolved to it was specialized.

“[In] 1989, I had access to what is effectively what people think of now modern VR.”

Luckily, at the same time, I was doing a thesis project at Stanford, and I had to choose a topic so I chose virtual reality. Scott graciously let me have access to this lab, so I just spent hours, months and months in that lab, and at the time I’d done more VR than anybody alive. I was just always in virtual worlds. Through that, I realized it wasn’t just a technological problem, it was just an entirely new medium. So that’s what my thesis became, was figuring out what that new medium was about.

WILL: And what is that new medium about?

MARK: Well, I did 20 different virtual worlds and you kind of have to be in all of them to start getting a feeling for what it really is good at doing and what it isn’t good at doing. One of the things to think about is that it’s always a first person perspective, and at first you think of that as being, well of course, first person like a camera view point, but in fact what it means is first person form a person’s perspective. So you are there, you have agency, everything is from your perspective. And as a result, there is an entire range of motions that we can give people that are first person emotions.

“There’s this new range of emotions that we can start authoring for.”

For example, guilt. You don’t really feel guilty if you watch a movie, personally guilty. But you can personally feel guilty for example if you shoot someone in a virtual world. So there’s this new range of emotions that we can start authoring for, and I think that’s one of the highlights of it as a new medium.

WILL: I’ve noticed a lot of filmmakers are using, trying to use empathetic strategies with their film and it seems to be very powerful medium for that. Are there other sort of emotional contacts that you really see people developing film for or see as virtual reality being the perfect medium for?

MARK: I’d like to react to the word empathetic, actually. Empathy is something we do that’s a third person emotion. We have empathy for another person, which makes sense in cinema. It makes sense in books when you’re looking at another person form a third person perspective. But in virtual reality, it’s not that you have empathy, it’s that you are actually having the emotions. So it’s a very different thing from my perspective.

“In virtual reality, it’s not that you have empathy, it’s that you are actually having the emotions.”

That being said, one the things I’ve learned at Sundance here is we’re going to have to make the transition. People aren’t fully aware of the power of this new medium, so concepts such as empathy and a lot of the worlds we’re currently seeing, they’re using found imagery, so to speak, with camera rays. I see it being transition steps to where virtual reality is really going to go.

WILL: Which is where?

MARK: If I skip a couple steps in how I normally introduce it, I’ll just jump to the end. I think we’re going to have worlds that appear to us today to be completely surreal. Where we don’t necessarily have 3D spatial grounding, where we have interfaces that are unlike anything we’ve ever head in the world before. It’s really hard to talk about just verbally. You would have to try some of my pieces to get a feeling of that. One piece I like in particular I did long ago. And it’s a world where none o the geometry make sense unless you’re standing in one point in space. And then perspective makes it all line up to make it appears as though you’re in the space, but the minute you move away from that 3D point, then all this geometry falls apart and can be an entirely different space. And that’s about as surreal as it gets.

WILL: That is really surreal. So as a film making tool, in these cinematic VR experiences, what have you seen as been a sort of successful and what have u seen that’s not been quite as successful?

MARK: I need to go back a step. The reason I’m in a school of cinematic arts, I in fact was in the Stanford engineering program, and I had a company making hardware and software called Fixed Based Labs. And this was all very technically driven. 10 years ago I decided that it wanted to create something that was as great as that NASA lab, but that the only way I was going to change the medium of VR would be if I had content creators, so I made a huge personal shift my moving to a school of cinematic arts and id dint know very much about movies at the time. I went from working with engineering students to art students.

“You’re not developing a character like an actor, instead the pieces develop in you as a character, or more of the point, you’re defining yourself as a character.”

I bring that up because that’s where I see these answers coming form. The only way I can answer your question is to say my students last year did about 5 different virtual worlds. Each one looked at a very different topic or area, and you have to experience them to get a feeling for it. I can tell you what some of those topics and scenarios were. One is this idea of point of view, and it’s very simple where your self-identity is being made. You’re not developing a character like an actor, instead the pieces develop in you as a character, or more of the point, you’re defining yourself as a character. So in this piece is a very simple little thing. You turn and you look at a mirror and you realize that you’re not at all a humanoid that looks like yourself. You’re in fact a mechanical robot.

But you sort of get a little tingle on your arms and when you see that, because all of a sudden you self identify as—oh, okay, I’m a mechanical being. So that’s one piece , for example, of something you could do. Second viewpoint is grounding. Getting the body involved—even though I just said everything is going to be surrealistic, it’s still really important to accept and embrace the fact that we have a human body and we need for that to get grounded into the virtual world. So there’s a couple different pieces on that, one of the students did a world. They started a company called Survios, where you use your body to really play with swords and you have fast rapid body motions, because they want to celebrate the body.

“you’re always moving, and you feel like you’re walking, but in the real world you’re walking in a straight line, but in the virtual world, in fact, he’s kind of making you walk around in a circle.”

Another work was done by Evan Suma who works at the ICT lab, and he’s doing what’s called redirected walking. So you walk in the virtual world, maybe 10 feet, but in the real world 10 feet. But in the virtual world, you can walk an infinite distance, because he’ll use perceptual tricks to move you around. So you’re always moving, and you feel like you’re walking, but in the real world you’re walking in a straight line, but in the virtual world, in fact, he’s kind of making you walk around in a circle.

WILL: Let’s shift focus a little bit. I want to talk to you a little bit about how VR as a medium is going to shape the narratives that we tell and what is story telling in the next five years going to look like in virtual reality?

MARK: Well, again, I’m going to react to the language, because I believe it’s not storytelling anymore. You’re making stories for the person. If we go on a hike right now in these mountains, we’re going to come back from that experience with stories that you and I made together, not a story that somebody told us. So again, back to the first person word. It’s a first person story making, and that’s not the same as storytelling.

“It’s a first person story making, and that’s not the same as storytelling.”

So I’m really interested in environments where people can make their own stories. That being said, the environment is being designed by an author and they’re definitely putting things there to help you make a story. But in the end, you have to believe it came from your mind. You can’t believe it was told to you.

WILL: So it’s all about sort of experiencing it through yourself through a directed experience?

MARK: Ultimately, yes. I think in the short term we will have story telling worlds, even to the point where we’ll sit around campfires and someone will tell us a story. That’s going to be interesting because the system could start using non verbal behaviors, looking at your body gestures, your head motions and whatnot, just like what a real story teller does to determine okay, I should tell more of this part, I should tell more of that part. So I shouldn’t short change storytelling. You literally could do it. But I think in the long run it’s going to be very different. It’s going to be about people making their own stories.

WILL: So with projects like project Syria, obviously VR journalism is something that is quite an effective experience. It really grabs you, you feel like you’re there, and that immersion can sort of lead to a more emotional understanding of what’s happening. So where does the ethical line lie for the filmmaker so that there’s not some sort of biases that are portrayed, or unintentional or intentional coloring of the event in a certain way?

MARK: Well, a couple things. So first of all, Syria is a good example of a combination of storytelling, a person making a story themselves through a first person emotion. It kinda ties everything together. You’re there, so you’re witnessing it and you’re coming up with the story. That being said, it has been authored by somebody telling a story, so you can’t pretend like the author doesn’t have an effect on the way the story is being told or in terms of the content. Ethically, that’s the challenge that journalists have always faced, and they’ll continue to face moving into the future.

“In one way, it’s ethically even more important than it’s ever been”

It’s just that the experience that the person walks away with is extremely first person. So I think the ethical—in one way, it’s ethically even more important than it’s ever been, and on the other hand, it could be fairly neutral where the person walks away with however they want to weave the facts together. So it kind of goes both way on the importance of ethics.

WILL: So I was talking to Nonny, and she was describing her relationship with Palmer and how that sort of blossomed and she said you were obviously involved in that. Can you speak on your perspective on what influence you might have had on Palmer and his creation of the Oculus?

MARK: Well, my goal is—Scott Fisher made that NASA Ames Lab available to me, and out of that lab came my company called Fakespace Labs, came a company called Costal River that ended up indirectly doing 3D audio, and Creative Labs ended up with the assets. Oh, and VPL Research started, or didn’t start, but it was a major participator in getting NVP into virtual reality, which was Jaron Lanier’s work. So that was a magical place that made things happen. That’s my only goal at USC, I’m trying to pay that back or pay it forward, whatever the saying it is, to create a place where amazing people can do things. Palmer was one of those amazing people. Nonny is another one of those amazing people. And then the graduates I’m talking about, we have other worlds interactive, which is two students just starting now. There’s like three or four sort of companies now that are all coming out of the lab. My job is to make that available.

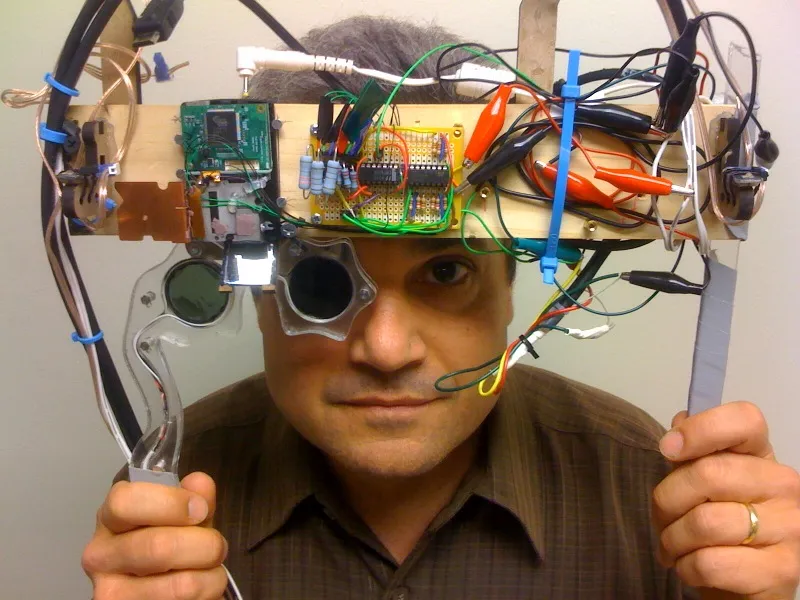

Toward that end, we did a lab is we decided the only way we’re going to really influence the field of VR as big as I wanted to was to open source designs. So we had a number of designs over the years that have been open sourced. One is extremely similar to the Google cardboard. The optical system is extremely similar to what became the Oculus Rift. Another one is extremely similar and was used by the Samsung Gear guys when they were developing theirs. We have a lot of software people need to do like optical root mapping. So, I believe those open source designs have influenced the field greatly, and that’s what academic research does. We have to get the work out to influence the word, and I’d put Palmer and Nonny and all these people as the way that work is getting out there. It’s just fantastic.

——

To find out more about the Mixed Reality lab and the cool work they are doing, be sure to check out their webpage.