Editor’s Note: This was originally published on March 29th, 2016 and is being republished today for the Oculus Rift’s third anniversary. The author of this piece, Blake Harris, has a new book out about the history of virtual reality and founding of Oculus called The History of the Future.

“Wait, hold on,” said Brendan Iribe, the CEO of Oculus, as he squinted with sudden confusion at the guests who had come to visit his company’s new Irvine office. It was December 2012, and there were four of these guys. Four of these guys from Dallas. “Wait,” Iribe continued, as his confusion grew to curiosity, “Who are you guys?!”

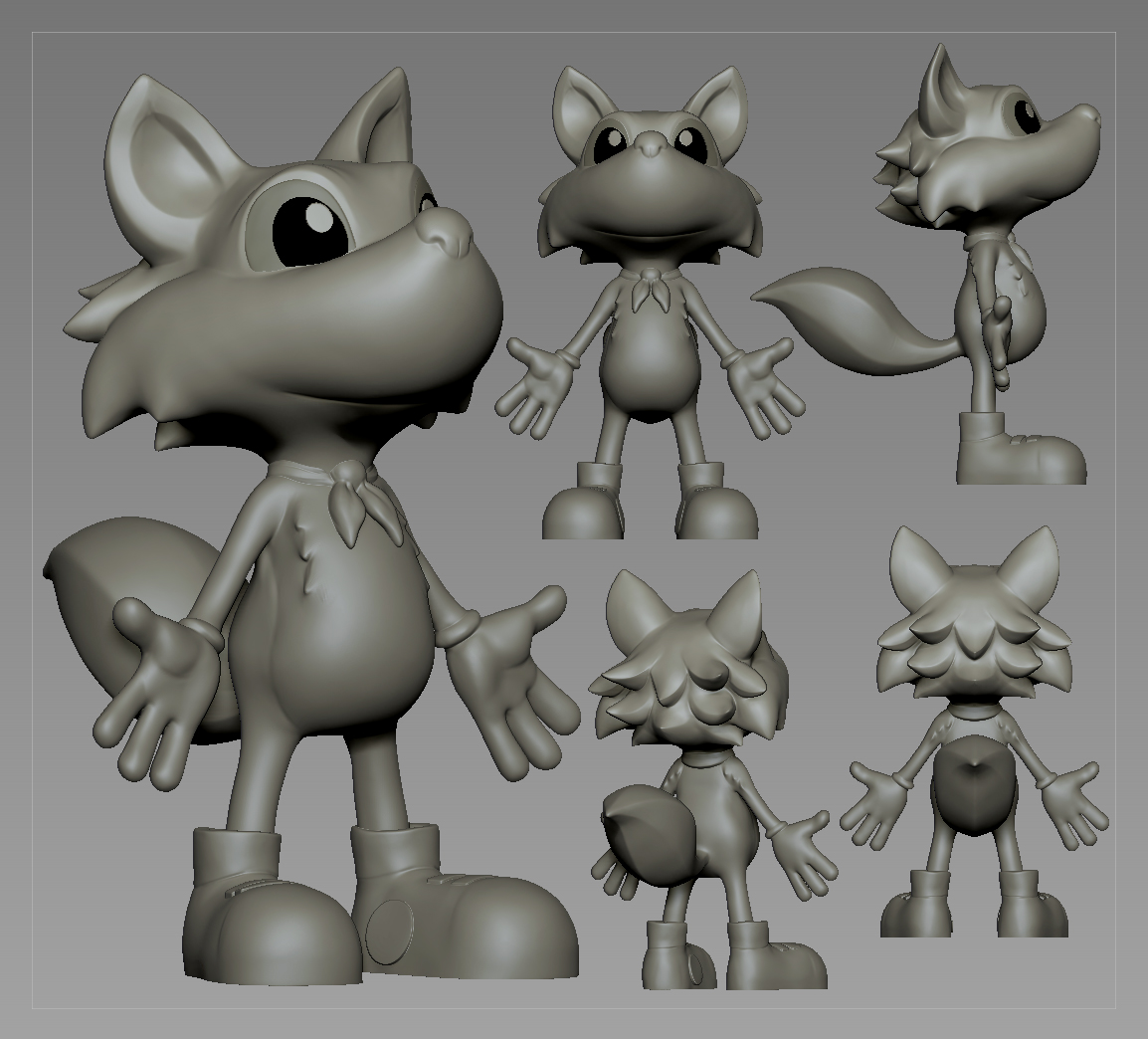

This is the story of who those guys were and how that awkward moment led to an intimate relationship and, ultimately, the creation of a foxy mascot named Lucky.

The Kings of Pop (Software)

In late 1997, when he was 19 years old, Paul Bettner began working at Ensemble Studios in Dallas. Six years later, Bettner’s younger brother David joined Ensemble as well. At some point between then and 2008—when the two would leave to start their own game company—Paul brought a chess board to work so that he and his brother could play a version of the game that can probably best be described as the opposite of speed chess.

The way it worked is one player would make a move and then, the next time the other player passed the board, he would make his move (whether or not the other opponent was present). The game would continue in this fashion—toggling back and forth, each at their own pace—until one of the two won. Sometimes it would take days, other times it would take weeks. And then, when it ended, they would start it all over again.

Certainly, the Bettners could not have been the first to play chess in this manner, but they were the first to embrace the asynchronous aspect and bring it to the iPhone. And not just any game, but one that seemed ideally suited for the iPhone, which Apple had just recently brought to market. In terms of a gaming device, the iPhone paled in comparison to dedicated handhelds (like the Game Boy or PSP) in almost every way. Except for one: it was always connected to the Internet, which made it perfect for this newfangled idea of persistent social gaming.

Text messaging meets gaming, that was the general idea, and in August 2008 Paul and David Bettner left Ensemble Studios to further explore this notion. To keep overhead low, they worked out of the McKinney public library and over the next few months they created a game called Chess with Friends. And in November 2008, Chess with Friends was released on Apple’s just-four-months-old App Store.

By no means was a runaway hit, but there was something unique about the release that kept the Bettners optimistic. Among those who did play the game, over half of them were still playing 30 days later. Compared to the love-‘em-and-leave-‘em games that populated the mobile market, the retention numbers for Chess with Friends were incredible. So the Bettners concluded that their problem wasn’t the gameplay, but rather the game itself. They needed something more fun. Something more playful. Something like…Scrabble.

In July 2009, with their business hanging on by a thread, the Bettners released Words with Friends. In July 2010, the game surpassed 7 million downloads. And in December 2010, for $180 million, Zynga acquired the Bettner’s mobile game studio (Newtoy, Inc.)

Although neither Paul nor David Bettner would ever complain about their windfall—they both felt grateful, and lucky, to have created something so valuable—the aftermath of the acquisition was a shock to their systems. At Newtoy, they believed they were making something more than games. “Pop Software” they called it, referring to a type of catchy, intuitive content that appealed to both traditional gamers and non-gamers alike. They felt that they had been on the forefront of something special and, without getting into the nitty-gritty of why they no longer felt that way, let’s just say that come 2012—two years into the four they had planned to stay—the Bettners left Zynga.

Following his departure, Paul Bettner didn’t know what he was going to do next. And he certainly had no idea that it would involve unleashing a fox in virtual reality.

Diversely and Relentlessly

After leaving Zynga, Bettner expected some sort of happily ever after. With money in the bank, autonomy reinstated and a wife (plus two young kids) at home, this was supposed to be the beginning of the good life. Except, as he soon learned, he wasn’t very good at that. Quickly he grew restless—feeling a gnawing need to create, build and collaborate—and started driving his family crazy with pet projects and creative fascinations.

One such fascination was virtual reality, and the string of what-ifs that kept popping up in his mind. What if virtual reality could actually be a thing? What if technology had advanced far enough to actually make it possible this time? What if three or four years from now, my wife (or even kids?) could be buying their first VR headset? So he reached out to an old friend, someone he believed could help him answer the question better than anyone: John Carmack, who around this time just so happened to be asking himself the same sort of what-ifs.

Professionally, these conversations with Carmack didn’t provide Bettner with any increased clarity about what he should do next, but personally—as a creator, as a technophile—he grew increasingly intrigued. Enough so to be one of only seven backers to pledged $5,000 or more to Oculus’ Kickstarter campaign. And, by doing so, received a reward that included visiting Oculus for a day.

Bettner scheduled that tour-the-office visit to coincide with another trip he was making to Oculus, a sort of how-can-we-work-together meeting. So in December 2012, Bettner and three colleagues flew out to Irvine to meet with Brendan Iribe and Palmer Luckey (twice). One as a developer, the other as a benefactor; which is what led to Iribe’s sudden confusion.

“Wait, hold on,” Iribe said scanning the table. “Wait. Who are you guys?!”

“We’re the guys who did Words with Friends,” Bettner explained.

“Ohhhhh,” Iribe replied. “I thought that meeting was tomorrow. I thought you guys were here for a Kickstarter reward, just to visit.”

Laughs, smiles, recalibrated handshakes. And any potentially lingering awkwardness was wiped away by the awesomeness of trying the duct-tape Rift prototype.

By the end of this meeting, Bettner knew that this was what he needed to do next. “We want to make things with you guys,” he said. “We don’t really know what we want to make, but if mobile taught us anything it’s that we need to let go off our expectations and just figure out what works. So why don’t we start building things on, like, a month-to-month basis with you guys and we’ll see what comes with that?”

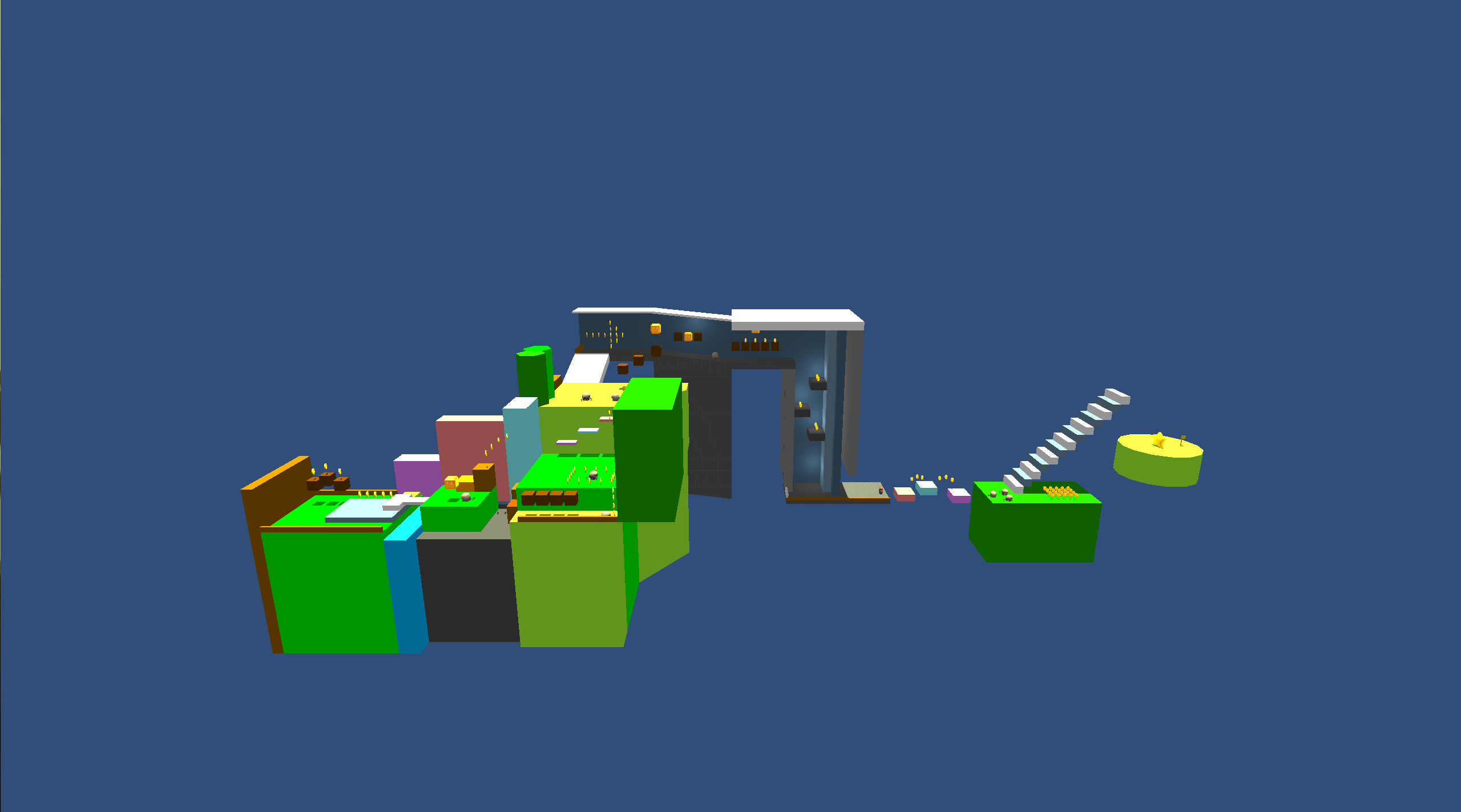

What came first was founding a new game studio (Playful Corp) and the idea of doing something like Wii Sports for VR. Not necessarily sports, per se, but a collection of mini games that showed off the potential of virtual reality. Not only did this seem like a logical creative approach (Wii Sports was the perfect vehicle to implement Nintendo’s “Blue Ocean” games-for-anyone strategy), but it also created a framework for Playful to experiment diversely and relentlessly.

During this time, they were churning out about one prototype a week. There was a Katamari-like game, where the player would subtly grow in size over time. There was a cooking game, where players would have to catch ingredients with a frying pan attached to their face. And there were a lot of games based around the mechanics of classics old and new (like Tempest and Doodle Jump).

Operating under the mindset that the fastest way to find the most compelling idea was just to keep building things, that’s exactly what they did. Brainstorming, building, bending (and then constantly re-bending) their expectations. And among the early batch of games, there was one concept that the guys at Playful had the most faith in: and it absolutely, positively was not Lucky’s Tale.

Super Capsule Brothers

From the getgo, Bettner and his team loved the idea that VR could enable us to do things that were otherwise impossible. Like flying. That was the big one. They thought flying would be the coolest thing in the world and so, in game form, tried things like putting players on the back of a giant dragonfly. Except every time they tried something like this, it was never as good as they thought it would be. It always felt too flat, like a matte painting and lacked any compelling sense of depth.

Meanwhile, as Playful spent 2013 throwing spaghetti at the virtual wall, Oculus continued to take off. In June, they drew in $16 million of Series A funding and then, in December, they brought in $75 million more. As the scope of Oculus and what they believed the Rift could be grew larger, so did their hopes for what Playful could build; instead of a potpourri of mini-games, they wanted a big launch title. Hitting a home run instead of a spree of singles and doubles would be a challenge, but it was one that the guys and gals at Playful relished.

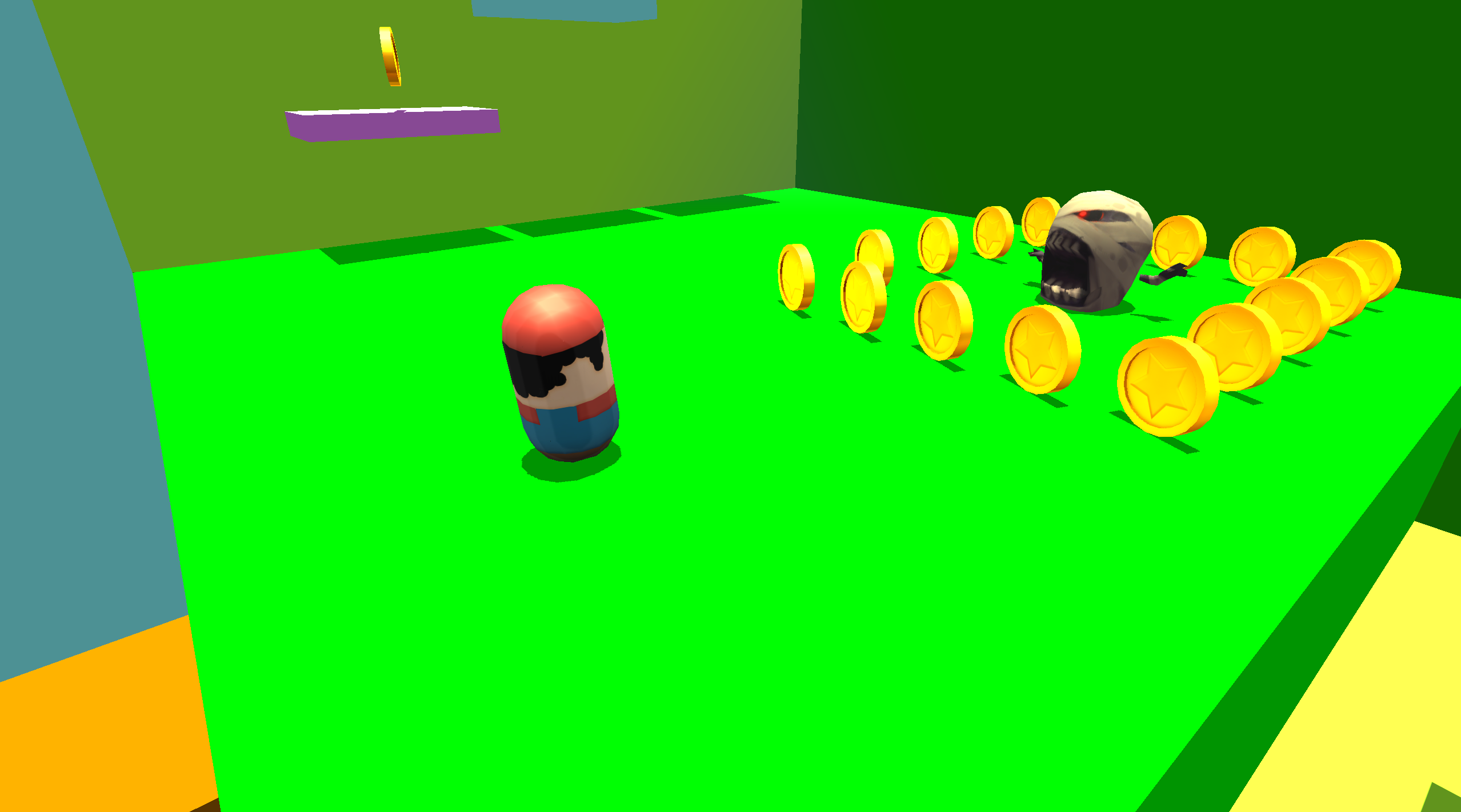

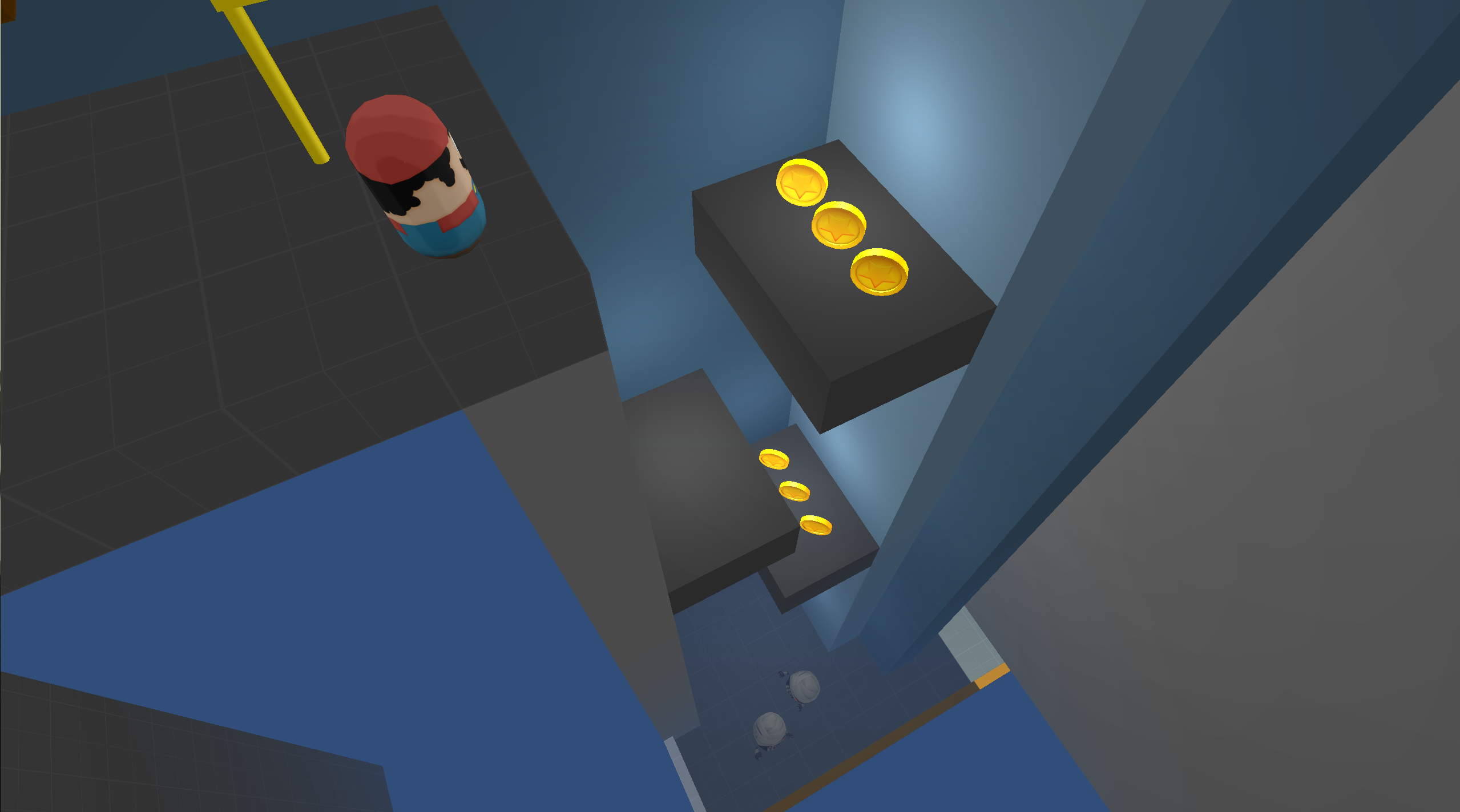

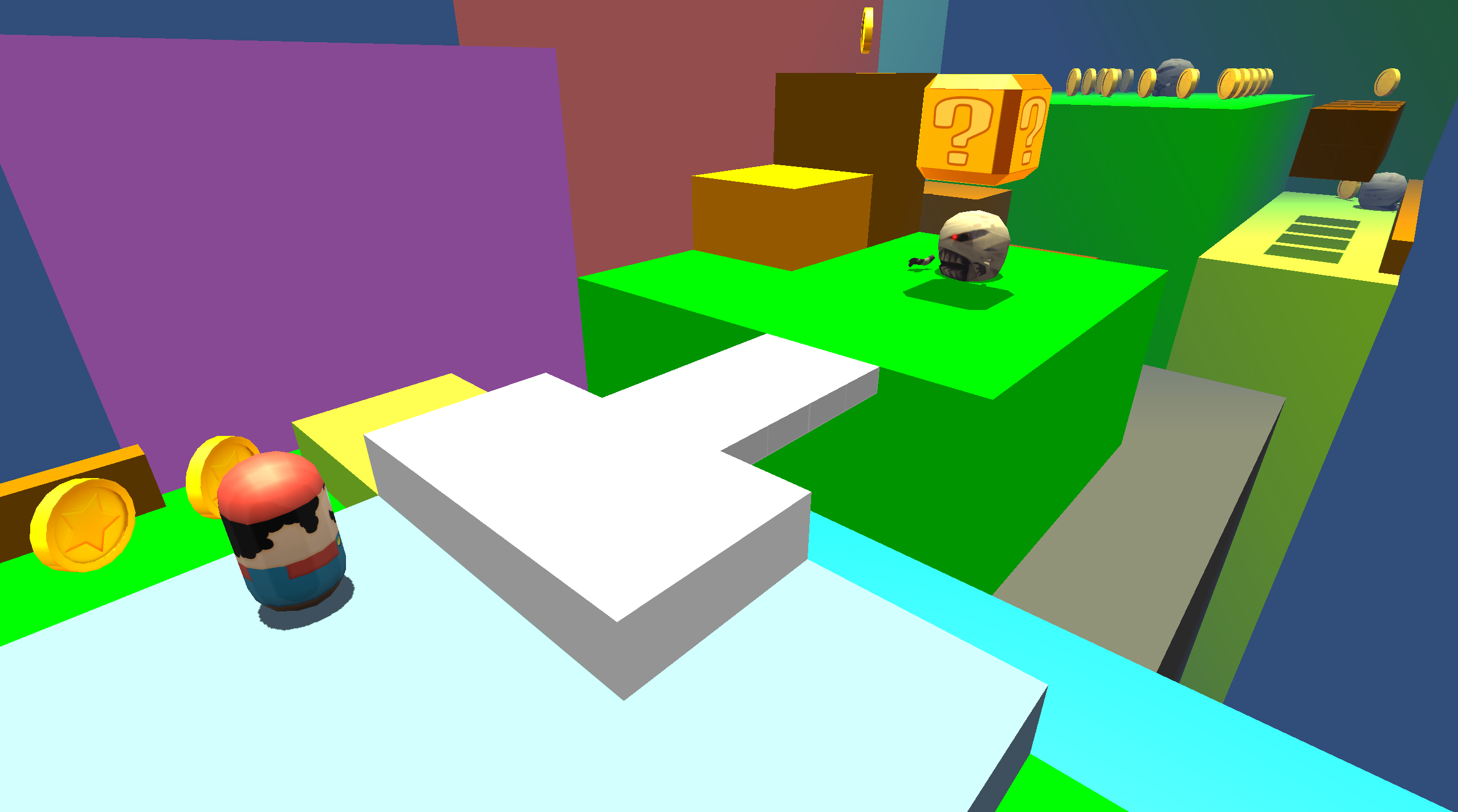

By this point, Playful had created forty games. Although none stood out as an obvious can’t-miss, there was one prototype they all believed in the most. But they had a little trouble admitting that at first because, in truth, it was among the ideas they thought least likely to pan out. This was the one idea that didn’t celebrate the first-person, immersive aspect that virtual reality offers; a third-person platformer called Super Capsule Bros. Inspired, of course, by Super Mario Bros., the prototype’s protagonist differed from its namesake. Instead of starring an Italian plumber, this one featured a blocky capsule (because that was one of the default shapes in Unity).

While the guys at Playful were initially skeptical about the type of game this was, they quickly realized why this concept worked: after decades touring the worlds of their favorite platformers (like Mario’s Mushroom Kingdom), they finally felt like they got to a place like this and explore. What they saw in that Super Capsule Bros. prototype was the first—and, still to this day, the only—VR experience that allowed for continuous, free-form locomotion through a virtual landscape without causing motion sickness. Or, put in terms that the kid inside of each of them was shouting through their skulls: magic.

Intermezzo: Q&A with Paul Bettner

Blake Harris: So you’ve got Super Capsule Bros., and it’s your favorite of the 40 games, but I was wondering if Oculus felt the same way?

Paul Bettner: I think, like us, they were surprised that a third-person game would work in VR. But after they tried it, they agreed that not only did it work, but they also saw the potential of what this could be. And another great thing about this game was that because it was a platformer, we didn’t need an excuse to put in whatever crazy mini-games we wanted. Because platformers have all sorts of crazy mini-games. So we were able to borrow from some of the other prototypes we’d built and bring elements of those into Super Capsule Bros., which, of course, soon became Lucky’s Tale.

Blake Harris: I figured that’s where this was headed. So tell me about how that happened. How did you go from capsule to fox? Were there other iterations in between?

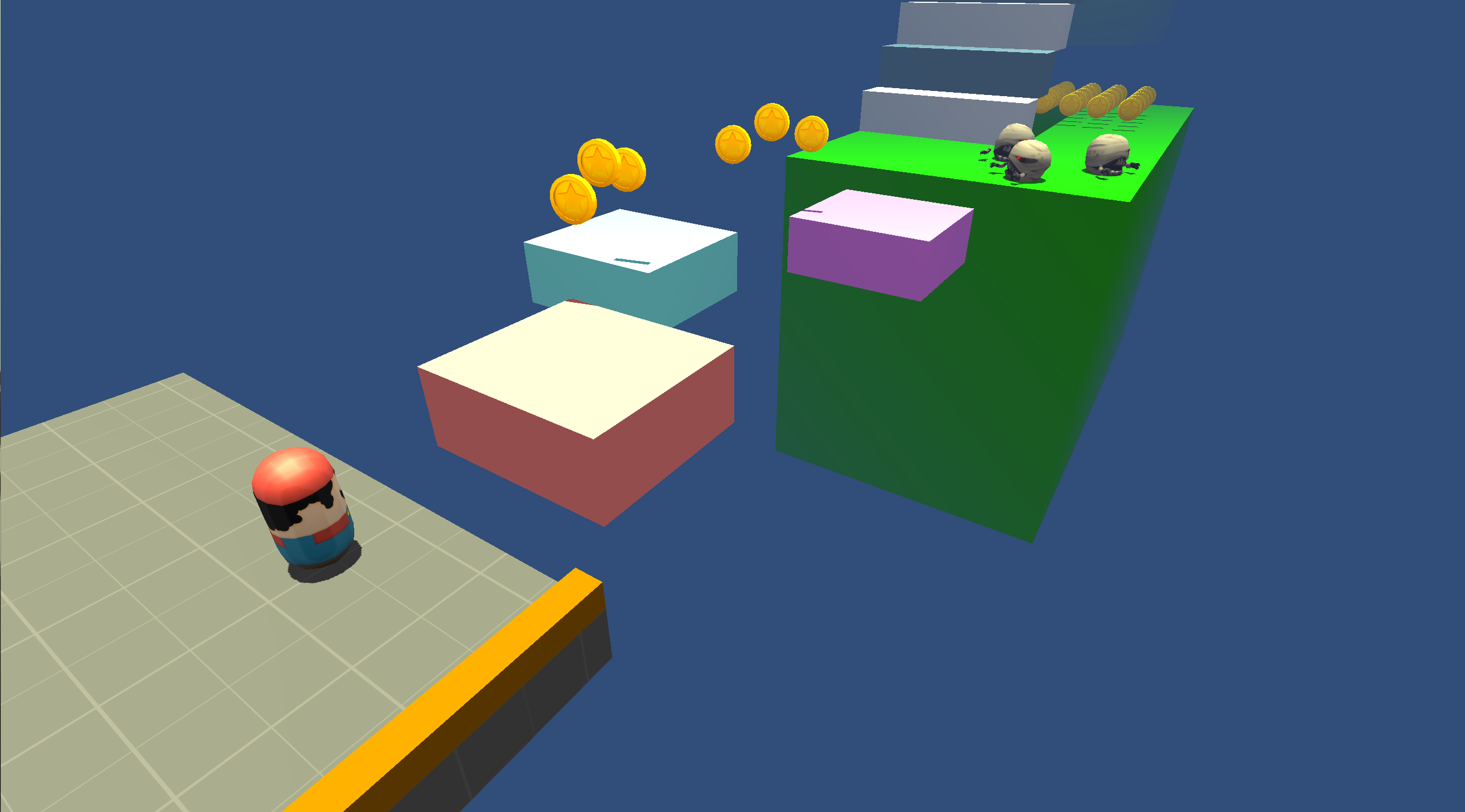

Paul Bettner: Oh yeah. There were four or five major iterations of the character before we finally got to Lucky. Early on, we knew we wanted to do an animal and a fox ended up working really well. He was cute, my kids were into that, and he also evoked something nostalgic. He looks like he belongs in plenty of games you’ve experienced before.

Blake Harris: He does. Given that he’s a fox, it’s hard not to think about Sonic’s old sidekick. But I think that association with Tails is about more than just being the same species. There’s some other quality about Lucky that evokes characters from that era.

Paul Bettner: You know, it’s easy to gloss over this, but I really think that—and I believe this is the reason why Oculus signed Lucky’s Tale as a bundled deal, why this even happened in the first place—when you meet Lucky in VR, there’s this feeling of new meeting the old. You have this incredible technology, you’ve never been inside of a game like this before, and yet you are meeting something that is immediately familiar to you and that most people have some nostalgic memory of. A character, whether it’s Mickey Mouse or it’s Mario, you’ve met a character like Lucky. So it’s kind of this childhood dream come to life. That’s where Lucky came from. We were trying to evoke that. We were trying to create something that felt familiar. Immediately familiar.

Blake Harris: Well speaking of iconic, mascot-type characters like Mario and Sonic, I’m curious why you don’t think there hasn’t been one in such a long time. Obviously there have been some since then—like, say, Crash Bandicoot and Spyro; though even they are both from the 90s—but why do you think it’s such a rare thing?

Paul Bettner: I really couldn’t tell you. I could say that it’s hard, because it’s definitely hard. You could ask our brilliant director, Dan Hurd. We’ve struggled and it’s been an uphill battle to create someone who looks and plays like Lucky. So that might be what keeps people away. Or maybe, to be honest, it could be the lack of diversity that exists in our industry. Typically, that’s not the kind of game that middle-aged white dudes play, nor is it what they tend to want to make. I really don’t know. But here’s one thing that I do know: it’s very frustrating from a consumer standpoint. I mean, I’ve got these little kids—a 7 year old, a 5 year old, a 2 year old—and we love to play games together. But the menu of games that are available to us is so thin. Like how many times can we beat Zelda Wind Waker together? We’re desperate to play more games like this, but there aren’t that many out there.

Blake Harris: That’s where you come in. Lucky’s Tale: uniting families everywhere!

Paul Bettner: [laughing] exactly. But seriously, I think that there’s definitely an element of us wanting to fill that void a little bit. And to be honest, that’s part of why we chose this direction for our first game and why the company is even called Playful.

Blake Harris: What do you mean?

Paul Bettner: Well, technology allows for entertainment to evoke plenty of different feelings. VR especially can evoke several strong emotions and responses. Fear. Adrenaline. Excitement. But what we want, the emotion that we’re going for, is happy. We want to evoke happy. When people put on a VR headset, we want to make them smile. And so everything we’ve done in Lucky’s Tale, all these little elements in the game, they’ve all been about trying to evoke that feeling of just pure joy, childlike joy, and I hope that’s the way that people react to it when it ships this week.

Blake Harris: Speaking of shipping, my last question for you is about how that came to be. Lucky’s Tale is one of two games bundled with the Rift. How did that happen?

Paul Bettner: Oh, that’s a good story…

Let’s Go!

In November 2015, Playful sent a final build of Lucky’s Tale to Oculus. Not long after, Brendan Iribe called up Paul Bettner. “I just sat down and played two hours of Lucky’s Tale,” explained Iribe. “Two hours, non-stop, without coming out of the Rift. I’ve never done that before, that much time.”

“That’s amazing,” Bettner replied. “I’m so glad to hear this.”

After they talked back and forth about the game for a bit, Iribe brought up the idea of making it exclusive to Oculus [for a period of time, at least] and bundling it with the Rift. “We’re going to put a deal in front of you,” Iribe began, speaking with the same sort of magnetic, it’s-all-happening confidence that persuaded many to work for him at Oculus. “We’re going to put a deal in front of you and you’re going to accept it because it’s gonna be that good.”

True to his word, Iribe soon put a lucrative offer in front of Bettner. But if there was anything that Bettner had learned from his Zynga experience, it’s that his long-term vision is more important than any amount of short-term money. Which, of course, begs the question: what was Paul Bettner’s vision?

Visions are hard to put into words, and even harder to put into numbers. So perhaps the best way to try and express Bettner’s outlook and ambitions is by sharing a story that he mentioned during one of our conversations. “This is something that we tell ourselves internally,” Better explained. “Imagine if you could put yourself in Walt Disney’s shoes back in the day. He saw this amazing new cutting edge technology called motion pictures and he believed it was going to change the world. Because what he saw was an ability to bring a character to life and make an audience fall in love with that character in a way that you just couldn’t do before. And the first time that you see Lucky come out of his house, and he looks up at you, makes eye contact, waves hello…I think people will feel something that they’ve never felt before. Then he points at you, points over to the level and says, ‘Let’s go!’ You just feel so connected to him in a way that you couldn’t have felt if this wasn’t VR.”

Sharing and spreading that kind of connection—one of joy, adventure and friendship—is, at least in my opinion, what lies at the heart of Playful’s vision. And so when Iribe presented his godfather offer—one that generously compensated Playful, wouldn’t require them to part with their IP and ensured that their foxy new friend would be experienced by 100% of those first traversing VR’s seemingly limitless frontier—it was, of course, impossible for Paul Bettner to say anything other than what Lucky himself would say: Let’s go!

Blake J. Harris is the best-selling author of Console Wars and will be co-directing the documentary based on his book, which is being produced by Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg and Scott Rudin. Currently, he is working on a new book about VR that will be published by HarperCollins in 2017. You can follow him on Twitter @blakejharrisNYC.