Magic Leap introduced a concept called Mica and called it “her” during a section of its 3-hour keynote this week about how an artificial intelligence could operate as an assistant to humans.

I feel like I met in person what Magic Leap showed in its video.

After the keynote, I sought out Mica and found her sitting downstairs. I was able to see her because Magic Leap equipped me with a Magic Leap One and told me to enter the room. When I saw her it was clear “she” wanted me to sit down with a wave of her arm, and I did.

I’ve described this entity I saw with short hair exuding micro-expressions and arm motions as both “it” and “she” which, if you’ve ever seen Ex Machina, is the core idea explored in that film. Mica was lit nothing like in the video, so her skin and hair didn’t look anywhere near as detailed or “real” as it does in the video. Still, it seemed as if the fidelity of her facial expressions were all there. That’s the part that seemed to mess with my brain. I felt like those micro-expressions were inviting me to care about the entity, and they were succeeding. Mica motioned for me to pick up a picture frame from the table and I didn’t catch the hint because I was too focused on trying to dismantle and understand the effect her expressions were having on me.

“Above all else, her facial movements are what connect you to her,” said John Monos, Magic Leap’s vice president in charge of “human-centered” artificial intelligence. “The lesson here: Mica is an ideal interface to the human-centered AI that evokes natural reactions from us.”

Why did I conceive of this agent as a female and were my reactions to its expressions and movements different than if it had been introduced or rendered in an androgynous or more masculine way? What if it hadn’t been introduced in the keynote as “her” and I hadn’t read a tweet suggesting it looked like Angelina Jolie from Hackers first?

One Twitter report suggests it is possible to interact with this entity and conceive of it as a genderless “system”. But that’s not how I saw it and I found myself wondering why it was rendered in such a way, and if my reaction to it was influenced by my perception of its gender. For me, Mica was basically a mirror or Rorschach test and it was freaking me out.

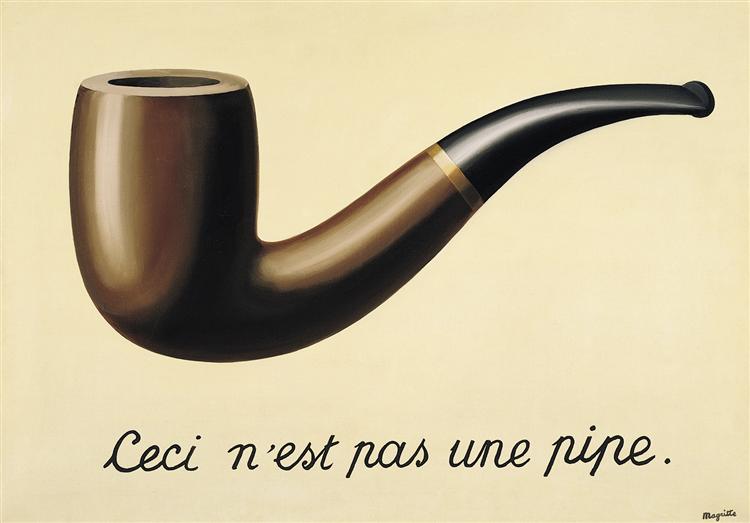

At one point a human from the real world told me what the next step was — picking up the frame from the table — and I sprang into action then. Mica then approached the frame and put her finger to the blank canvas — magically revealing Rene Magritte’s “This Is Not A Pipe” there in the center of my vision.

She then plucked the “pipe” from the frame and held it in her hand, giggling before excusing herself and disappearing behind a bookcase. Would I have reacted to it differently if Mica had been rendered with more masculine features? Mica’s presentation was a slight nod to work by Marina Abramović as an artist who returns the gaze of someone viewing their work.

“For me it is more inspired by in art history, and also in the history of technology, that women, and female characters, are so often looked at and we all — regardless of who we are — become the possessor of the male gaze,” said Alice Wroe, creative designer on the project. “So for her to sit down opposite you as the first time you meet the digital human and for her to return your gaze is really powerful and important and creates a space of equality and reciprocal looking. I think is quite powerful. It’s kind of a slice of feminist tech history I think. For me, when I see people walk in and they can’t help but smile at her and grin, I get a jolt in my stomach every time because she is sat there and people can’t help but smile back and that is so special and important. And when I see people like you lean in and look at her and I know that she’s doing the same back at you — she’s looking around your head, she’s watching as your shoulders move from side to side — I feel like it’s an important statement about looking back at feminism.”