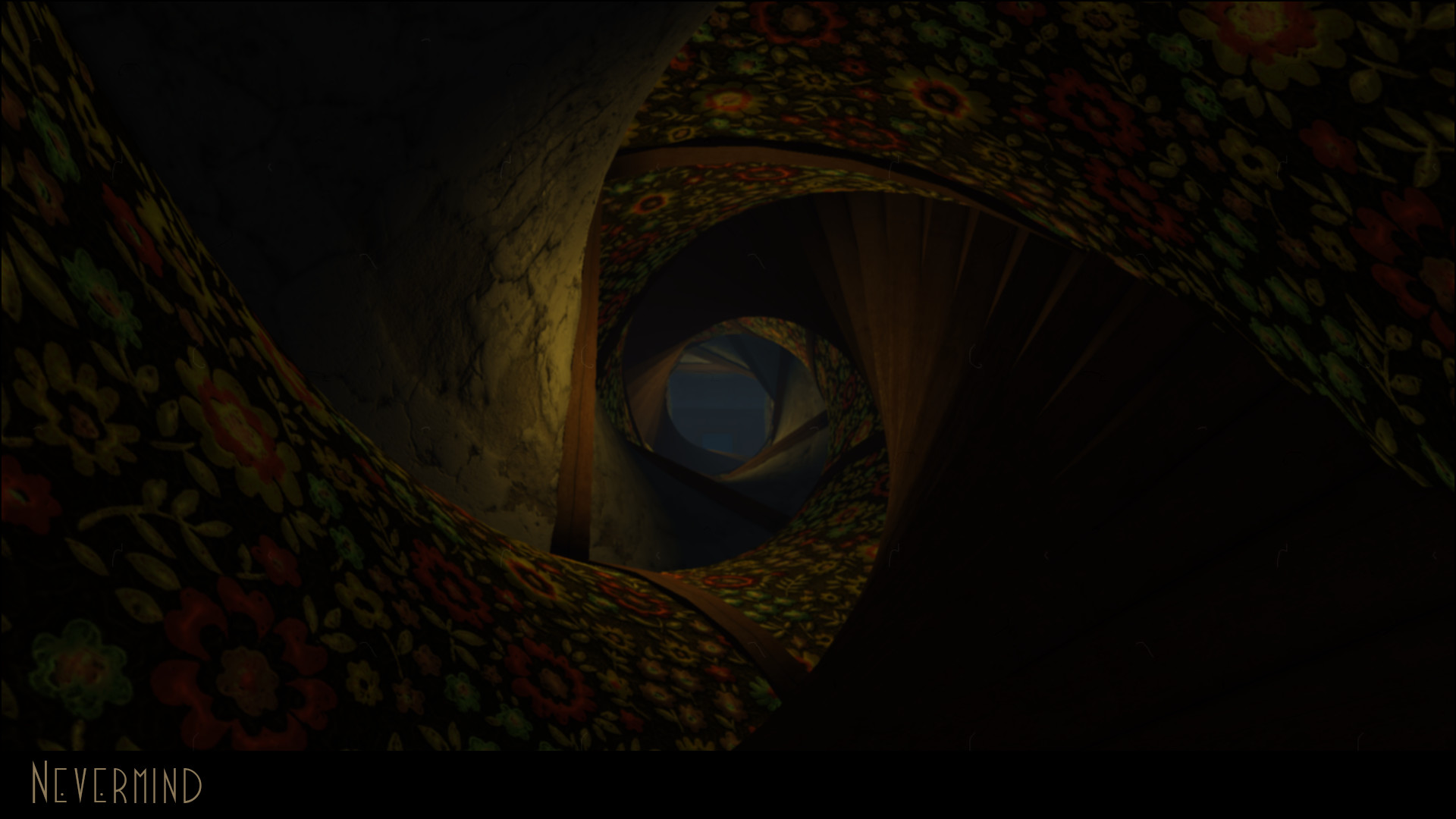

Not all fears are equal, especially where uniquely individual humans and their psyches are concerned, but Nevermind certainly attempts something novel with its Inception-like narrative, even when it becomes a supremely frustrating experience.

In the role of a medically trained “neuroprober,” players must embark on an adventure through the minds of five patients suffering from a range of mental and emotional illnesses. Much like Christopher Nolan’s film Inception, these mental afflictions manifest themselves in wholly unique and often fascinatingly inventive ways. Like how a female agoraphobe’s vision goes dark the further she gets from her apartment door, or an accomplished pianist forgets her music during an important performance thanks to her Alzheimer’s, or in the mind of a patient attempting to discern what really happened between her mother and father, the tall doors and furniture of her childhood home remind the player just how weak and ineffectual a child’s perspective is in a broken home.

Developer Flying Mollusk is, admirably, very upfront about how serious the depictions of these illnesses and their effects can be, and even weaves a message of the importance of self-care throughout the game. Needless to say, it would be difficult to recommend this as an experience for people who’ve already struggled through the illnesses on display, rather than unafflicted people wanting to glean a better understanding of them.

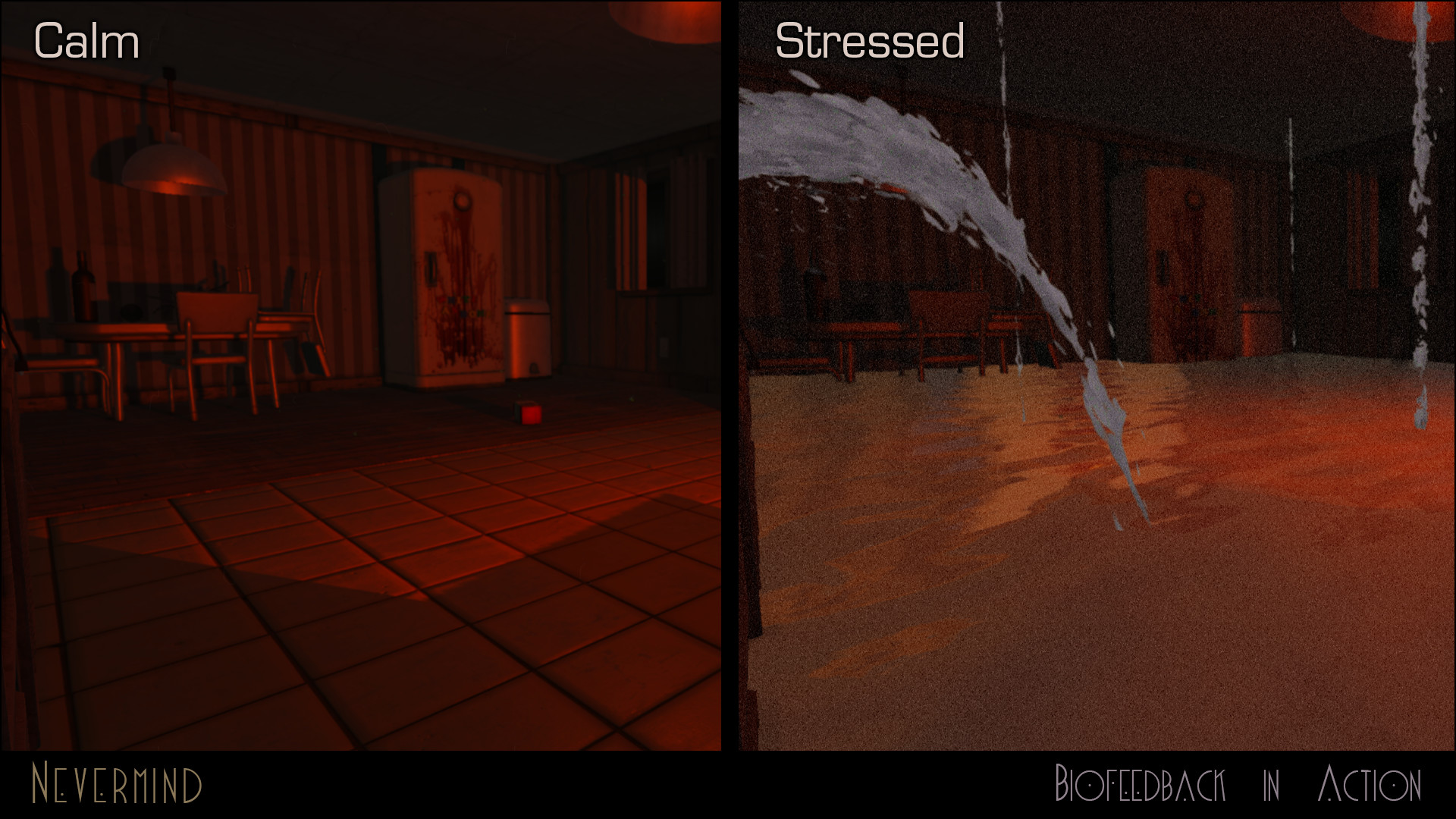

Where Nevermind really sets itself apart is the incorporation of biological feedback sensors used during gameplay which can significantly alter the perceived state of whichever environment or scenario the player traverses. Should the player’s heart rate begin to accelerate, their vision becomes blurred, and the environment begins to take on a darker tone. While the sensors can oftentimes be way too sensitive depending on the particular one you’re using, the game does provide the option to modify how aggressively it reads your vitals, or turn them off altogether.

The original game previously released in 2015 as a traditional PC game, so now with the inclusion of VR, Nevermind’s more intense moments become that much more surreal. While I may never know the reality of living through an abusive relationship, I most certainly know the horrors of stage fright. The scene which Flying Mollusk crafts for such a scenario may stick with me forever.

A round of thunderous applause greets you as you venture out onto the stage, past a small gauntlet of chairs and music stands. It quickly becomes apparent just how skewed and unnatural the sea of empty audience chairs is, reaching higher into the distance than any theater I’ve ever seen, lending an eerie sense of otherworldliness to the experience. This sense of scale – again, like Inception – is a relative constant throughout Nevermind, separating the cerebral world from the physical, making for some of the most unique environments horror and narrative games have seen in the last few years.

Beyond the narrative hooks that Nevermind’s virtual reality and bio-sensor implementation give it, each patient’s tale plays out in similar fashion. Stories are bookended by relatively convincing patient narration explaining their thoughts and struggles, and it’s up to the neuroprober to find “snapshots,” collectable pictures with accompanying text that illustrate the reasons for each patient’s turmoil.

Where Nevermind begins to lose its way, however, is the implementation of puzzles that are, at best, innocuous and occasionally tie into the narrative in meaningful ways. At worst, and most often, they are maddeningly frustrating and effectively neuter the impact of each patient’s story.

On one end of the spectrum, a puzzle involving the Alzheimer’s patient’s struggle to remember her music is both evocative and inventive in a way that truly captures the nature of musical performance. After the aforementioned walk onto the stage, the invisible orchestra swells into an early crescendo, setting you up for a perfect and soulful piano melody. Six keys are marked with red ink, indicating the proper notes easily enough, but as the ink fades and notes sour, the growing whispers from the audience shook me to my core. It perfectly illustrates the feeling of helplessness a major blunder (much less one you have no control over) can have on a performer.

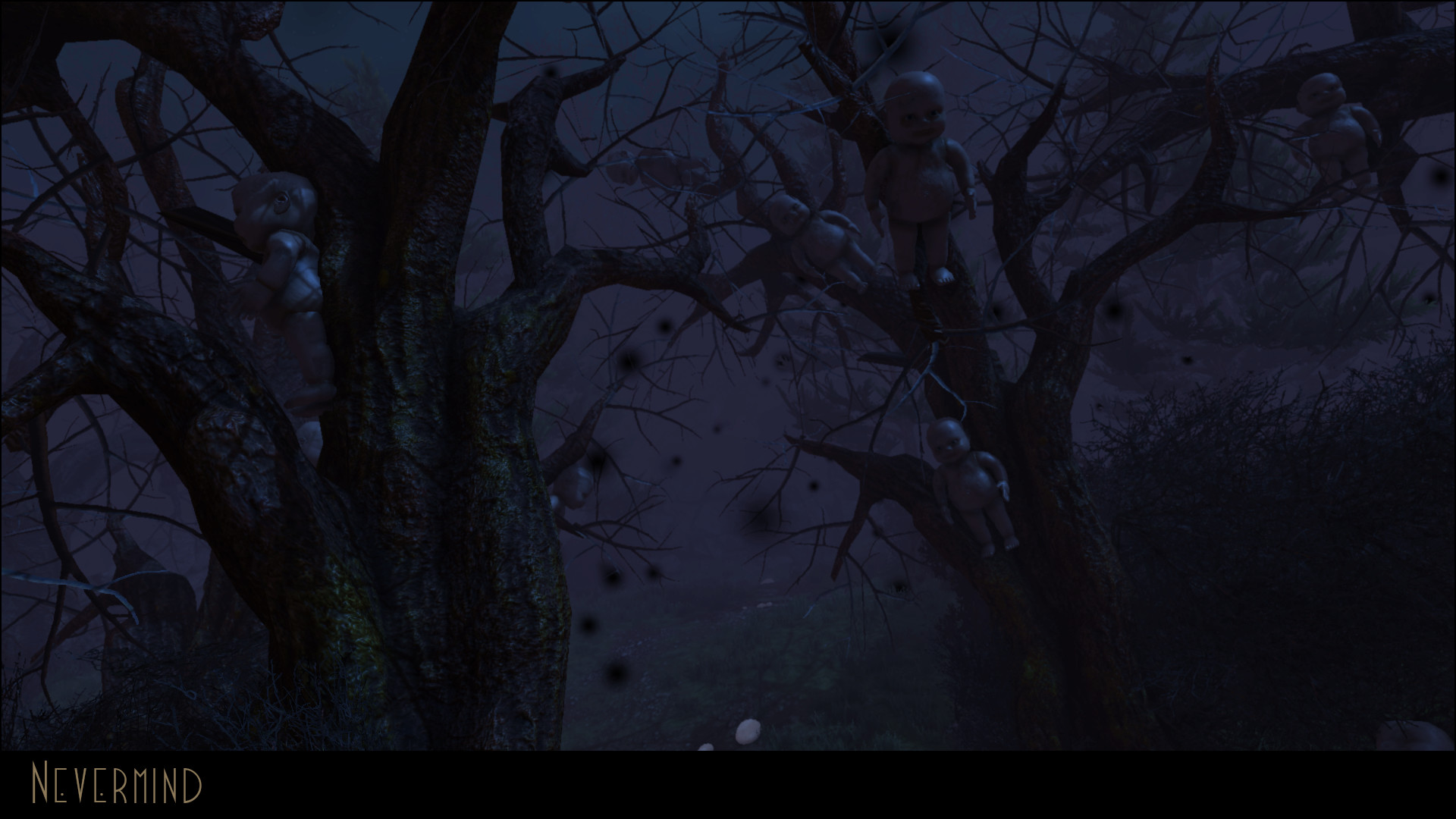

On the opposite end of that, the game attempts to illustrate the demanding regiment the patient was subjected to as a child by forcing you to memorize note patterns on increasingly macabre statues of human flesh and instruments morphed together in a procession of dark rooms. After the brilliant setup, these puzzles immediately halt any sense of foreboding or emotional impact the episode had built up to this point.

They’re little more than rough exercises in memorization, or worse, trial and error. The game provides you with hints scrawled on nearby chalkboards, but if the game senses so much as a slight rise in body temperature (probably thanks to frustration or your heater being on), your vision is obscured and the hint becomes impossible to read. I counted at least nine times I needed to turn off the game’s sensor feedback just to be able to see the puzzle, even after calming myself with some deep breaths.

As the game progresses, each narrative becomes plagued by a number of poorly designed puzzles, either with little to nothing in the way of context clues or frustrating fail conditions.

It’s a problem that many narrative-focused games seem to have these days, where arguments for “gameplay is king” reign supreme. The truth is, if your narrative is the key element of your game (I assure you nobody plays “walking simulators” or horror games for their mechanical prowess,) it seems imperative that everything act in support of that. While most of Nevermind’s puzzles do attempt to tie into each narrative with some visual or mechanical element, it’s often poorly executed.

For the first time in my career, I was actually driven to ask the developer for assistance in solving a seemingly mind-numbing puzzle not once, not twice, but three times. Before that, I consulted online guides for a smaller number of rough instances. I’d hate to think how a player without my resources would fare.

As it stands, Nevermind is still a unique game, and at times even an objectively “important” one. To see such subjects like mental illness, suicide, or abusive behavior approached with such inventive and engaged intent isn’t something the games industry dares touch as often as it should. Flying Mollusk should be commended for bringing such an experience to VR, where it can truly shine by putting the player in the shoes of each individual patient even more intently. It’s frustrating that a lot of its impact as a vehicle for empathy might be neutered by poorly incorporated puzzles, but it’s certainly something for the history – and medical – books.

Nevermind is available on Steam right now with support for the HTC Vive, Oculus Rift, and OSVR at a price point of $19.99. Read our Game Review Guidelines for more information on how we arrived at this score.