Sprawled across the Anaheim Convention Center, VR was everywhere at the SIGGRAPH computer graphics conference this week.

While Oculus Rift and HTC Vive headsets were visibly sprinkled around dozens of booths showcasing new and emerging technologies, chipmakers NVIDIA and AMD were invisibly at those same booths powering all the VR experiences. At the core of practically every PC-based VR system is an expensive NVIDIA or AMD graphics chip. What exactly is expensive? Graphics cards to drive Rift and Vive experiences at the recommended specification are getting as low as a couple hundred dollars now. What SIGGRAPH showed, though, was AMD and NVIDIA preparing next generation graphics technologies at the other end. These next generation chips can cost more than $5,000, built for professionals. AMD, for example, announced a “Solid State Graphics” initiative that puts a terabyte of memory on a graphics card for increased performance, coming in 2017. Developer kits cost $10,000.

NVIDIA showed off a research project teaming with eye tracking company SMI that uses a technique called foveated rendering to save vast amounts of processing power by trimming out detail from a VR scene in a way that you’ll never notice. It works because detail is only removed from your peripheral vision.

Two demos in particular from NVIDIA really brought home the types of things next generation high-cost business workstations can do for professionals.

Building A Car In Your Garage With A Friend

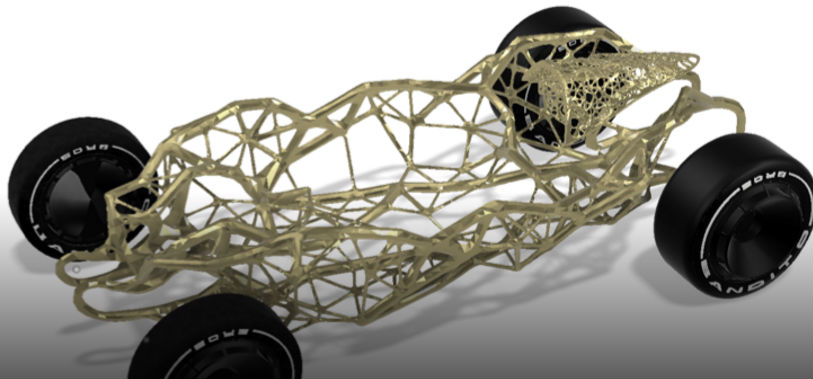

There are two laser base stations in a room, two Vive headsets and two of the beefiest PC workstations I’ve ever seen hooked up to it. I put on one of the headsets and in front of me there’s the chassis of a car that doesn’t exist yet. As I look to my right, I see the disembodied head of Luigi from Super Mario Bros. coming to life. I figure that means I’m Mario in this particular world.

So I’m in this world with Luigi and we are told we can give each other a soft high five with the VR controllers. We do and it’s cool, but this demo isn’t about two people being in the same room and collaborating in VR. It’s about two people building and customizing a car together spread across two computers in two different parts of the world. The two of us just happen to be in the same physical room for this demonstration. What matters is that we’re in the same virtual room.

Each of us can teleport to specific regions in the room but we only want to teleport to the same area. If we don’t, we could run into each other as we walk around the car and examine it up close. On a table nearby we are able to manipulate the entire vehicle — putting in tires, seats and a carbon fiber shell. I crouch down in the real room to sit in the front seat of the virtual car and take a good look at the view from here.

The demo was the result of a team based in L.A. called Hack Rod creating a car engineered with artificial intelligence. To do it, they used software from Autodesk and NVIDIA’s chips to develop new designs for a car chassis. It was all based on data gathered from test drives that was fed into a computer.

The demo was one of two professionally-oriented VR demos given by NVIDIA at SIGGRAPH that focused on multiplayer VR experiences, the other provided by Dassault to show off city planning.

“The future of VR will be collaborative. Teams coming together in VR to work on models and projects, interacting to make better decisions faster,” said David Weinstein, Director of Professional Virtual Reality at NVIDIA, in a prepared statement. “Collaborative VR means businesses no longer have to fly dispersed teams to a singular location to make collaborative design decisions. It streamlines the design process and saves time – which translates into cost savings.”

Even if it ends up costing $20,000 or $30,000 to equip two offices with this kind of VR prototyping solution, that’s still a bargain if it saves the company money or time in the long run.

Manipulating Time and Scale

The next demo was in an Oculus Rift with Touch controls. I found it to be the most impressive demonstration of VR technology to date.

NVIDIA is building a new headquarters to open next year and at intervals throughout the construction process the company has taken what are essentially point cloud scans of the entire facility in 3D.

What this means is that in VR, powered by one of the beefiest graphics cards NVIDIA can muster, I could visit the headquarters with control over time and space in a way I’ve never seen before.

One moment I had in my hand a tiny model of the entire NVIDIA headquarters I could examine by leaning in close. After a few moments of making stretching motions with my arms, I was standing in the middle of the facility at full size. This was like catnip for a VR nut — I couldn’t stop scaling the world big and small.

Then, with a flick of my thumb on the Touch controls, I could flip backward and forward in time to see the headquarters as it looked at different times. I could walk around the room to see it from different angles. At any time I could reach out and pull a portion of the world closer to me.

VR software like Titans of Space and SculptrVR play with scale in really powerful ways, the former for education and the latter for creation of virtual sculptures. This NVIDIA demo, however, was a representation of a real world structure coming to life before my very eyes. I could examine any part of instantly, taking in the view from a helicopter, a position on the ground or anywhere in between.

What’s Next?

These demos from NVIDIA were previews of features that will be standard across all high-powered VR devices in a couple years. The manipulation of virtual time and space of even the most complex 3D worlds is something truly awe-inspiring, but collaboration, where you can save time and money for your business by doing critical work tasks in VR, could be the thing that makes people need to use the technology every day. As Moore’s Law continues to increase the power of our computers, the features I saw rendered by workstations costing several thousands dollars are simply previews of things the rest of us will have in a few years.