With the release of the TPCast wireless adapter (for Oculus Rift and HTC Vive), and now the official HTC Vive Wireless Adapter, many have been wondering whether Oculus are working on a 1st party wireless solution for Rift, or whether they plan to incorporate wireless in the future version of Rift. These adapters are, however, very expensive, large, bulky, and the transmitter might have to be mounted on the wall to work well. This is because they transmit a high frequency (60 GHz) signal over a large field of view that generally requires line of sight to the headset.

Narrow Beam Following Positional Tracking

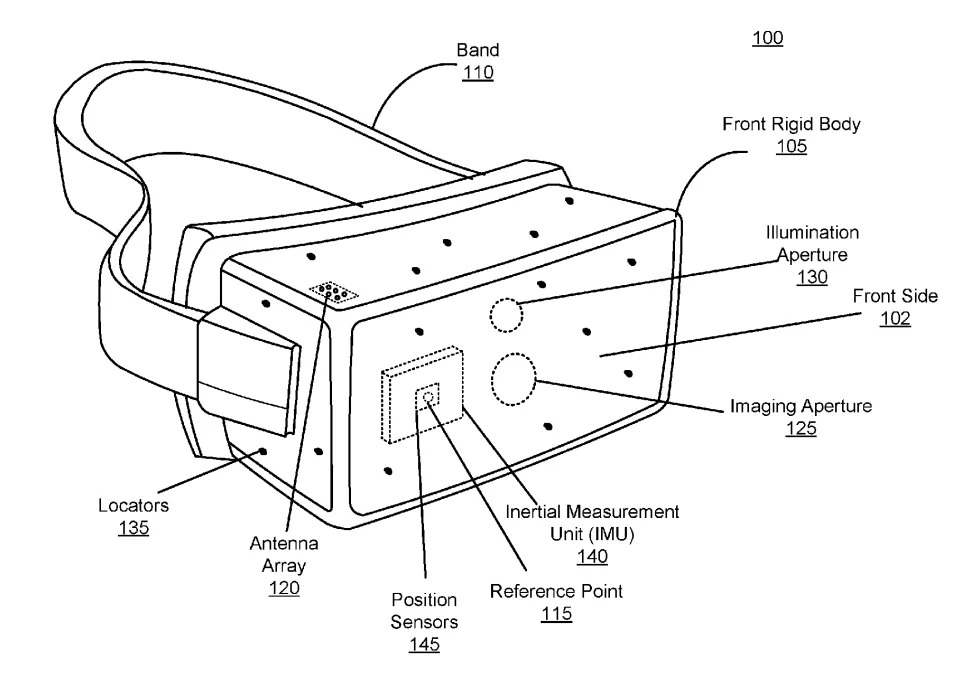

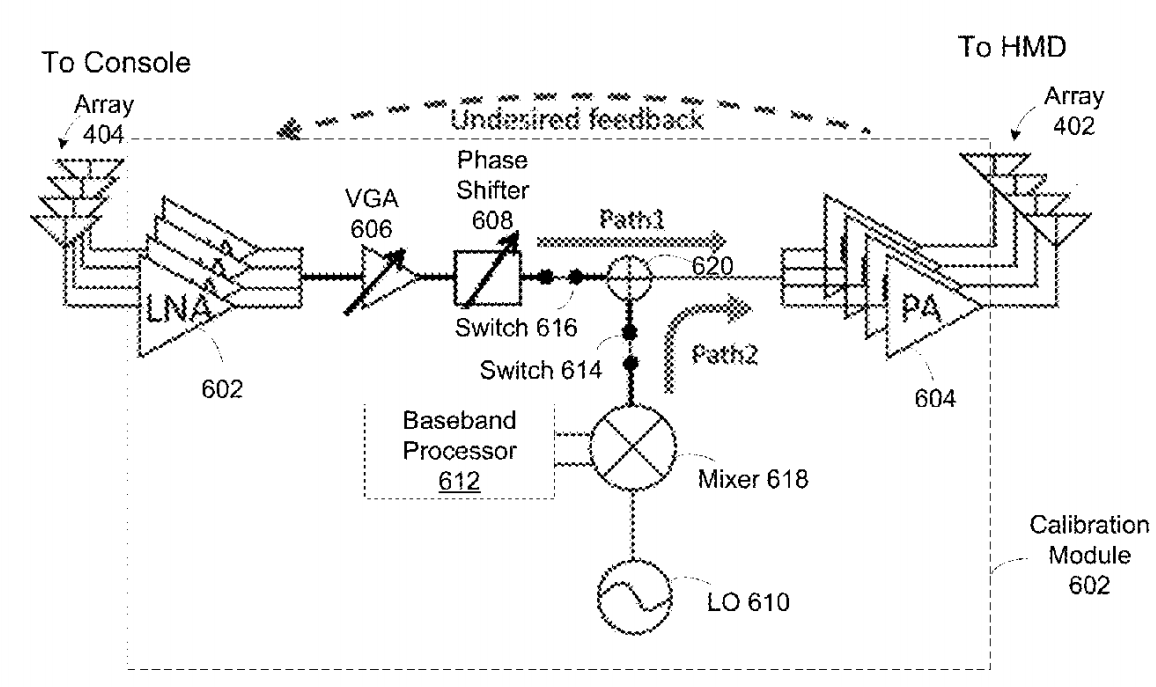

Late last year, Oculus filed for a patent on a technique that would have the wireless transmission system use the positional tracking data from the headset to send a relatively narrow beam to the direction of the headset, instead of all over the room. When the headset moves position, it could inform the transmitter of the new position over regular low bandwidth omnidirectional wireless (similar to Bluetooth) and then the transmitter would direct the high power beam at the new position.

The advantage of this approach is that, because the transmitter only has to send the wireless signal to one spot in the room, less power should be needed overall. This idea could be used to lower cost in future wireless VR setups. The high power transmitters used in the Vive Wireless Adapter and TPCast greatly contribute to the $300 prices, so the need to find lower cost solutions is clear.

The patent mentions that one of the possible protocols for the beam could be 802.11ad, otherwise known as “WiGig”. WiGig is an existing 60 GHz standard widely used for wireless displays such as wireless monitors, and is actually used in the HTC Vive Wireless Adapter.

Fighting Occlusion With A “Relay”

But what if the view between the transmitter is disrupted? Oculus applied for another patent for using an assisting “relay” in the room. When the view between the transmitter and headset is blocked, and therefore the signal is blocked, the transmitter would instead send its beam to the relay, which would act as repeater.

Coming to Rift 2?

In his “5 year’s from now” predictions made at Oculus Connect 3 in 2016, Oculus Chief Scientist Michael Abrash said that he expected to see wireless headsets “at the high end”, but that there is “no existing consumer electronics link that’s up to the task”. This may be why Oculus began researching a custom (and patented) wireless solution.

Abrash also mentions that without foveated rendering (rendering at a low resolution everywhere except where the user’s eyes are looking), achieving wireless on PC would be very challenging. In Oculus’ foveated rendering patent, originally filed back in 2016, the company describes a display driver which can handle different resolutions for different parts of the image, noting “the devices may communicate wirelessly instead of through wired connections”. This is usually called “foveal transport”, and means that much less data needs to be sent compared to sending the full resolution frame. As Abrash suggests, this is likely the only practical way to deliver wireless with a significantly higher resolution headset than today’s Rift.

One fact that hints against the Rift’s successor being wireless, or at least against it being wireless by default, is that in July Oculus joined the new “VirtualLink” USB-C single cable standard for connecting wired VR headsets. While it could be argued this would just be to connect to the wireless transmitter itself, the specification for VirtualLink mentions the cable providing power for on headset cameras and sensors. This could indicate that if this wireless technology does make it to the next Rift (to be clear: it may never), it might be an optional add-on, rather than a part of the base package. Even if this tech is lower cost than the $300 TPCast and HTC adapters, it would still probably not be cheap.

These 3 patents paint a clear picture of the approach Oculus is taking in their research on wireless PC VR – a narrow directed beam using as little energy as possible, leveraging foveated rendering to send as little data as possible, with support for relays to defeat occlusion. While all this technology may never see the outside of Facebook’s research labs, if it ever does it could be a game changer for wireless VR on PC.