So here’s a confession: before Oculus announced it was closing down Oculus Story Studio last week, I hadn’t actually seen any of the team’s VR movies from start to finish. In the ever-growing backlog of VR content that continues to increase by the week, I just hadn’t set out the time to sit down (or stand up) and properly dive into them yet. Fueled somewhat by guilt, I decided now was as good a time as any to do that.

So I did VR’s first binge watch. It lasted about half an hour.

I think we can all agree Story Studio didn’t get the time it deserved to realize its full potential, though it’s important to understand that its goal wasn’t necessarily to be the leading VR filmmaker. If its mission statement from early 2015 is to be believed, this was a team that was more interested in charting the path to making effective VR movies so that others might walk it. Obviously its films were meant to be enjoyed, but the studio wanted to be educational, dissecting both its success and failures for the next generation of VR filmmakers to learn from.

So the question is simply this: what did we learn? Let’s take a look at the three movies it made over the past two years to find out.

Lost

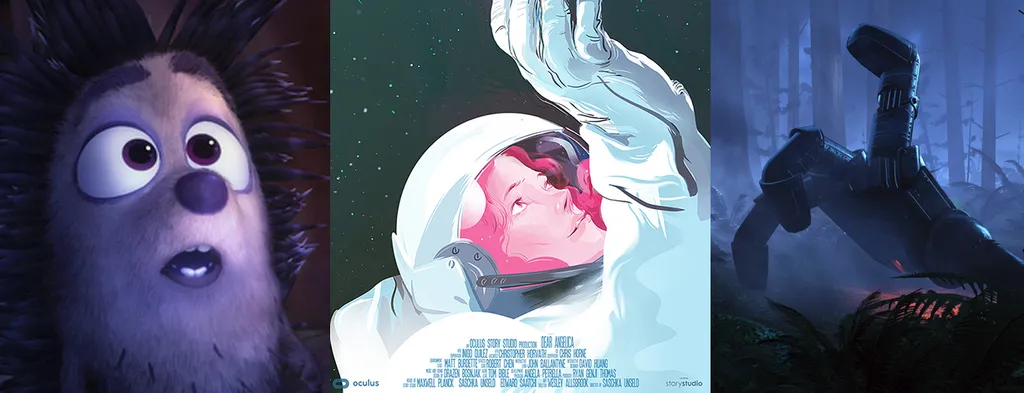

As Story Studio’s first project, Lost displays earnest beginnings and a big heart that leave you a little underwhelmed. Lasting mere minutes, it follows a detached robotic arm, lost in a forest and obediently calling for its owner. You can see a whole lot of Brad Bird’s The Iron Giant in it.

You might call Lost ‘VR Movie Making 101’; it feels like a template for the basics more than anything else. The camera is nestled away behind some leaves, making you a hidden onlooker, privileged to be witnessing the scene unfolding in front of you, a similar technique to when your friendly rabbit pal hides behind you in Baobab Studio’s Invasion. It also plays with some of the bread and butter elements of VR immersion, like the wow-factor that comes with scale, the tug of the heart strings that you’ll feel when you make direct contact with a saddened character, and the inescapable allure of watching things buzz around your head. It’s very much a lesson in the initial wonder of VR, much like some of the early content from studios like Within.

The result is something wonderfully sweet; the lost hand melts your heart by wagging its tail as it waits for its master to come and retrieve it. As well-intentioned as it is, though, Lost ultimately does little to leave an impact on you as its credits start to roll. It was just the very tip of the iceberg of what VR can do with storytelling, more of a trailer for what the studio and the wider industry might be able to flesh out one day. For Story Studio itself, though, it no doubt laid essential foundations for the team to get up and running.

Henry

Henry, meanwhile, was a much bigger deal, proudly touted by Oculus for winning an Emmy after launching alongside the Rift (as did Lost, though with very little said of it). Here was Story Studio’s first real push into — I’ll just say it — Pixar territory. It resembled the animated shorts the studio would run before one of its bigger features.

Henry the hedgehog, as Oculus executives would repeatedly tell us, just wanted to be loved. Sadly whenever he attempted to hug someone, he ended up stinging them with his spikes. You joined the little critter on his birthday, where he prepares a little party for himself and makes a wish for some real friends. Would you believe that he might just get what he asked for?

Though undeniably charming, it’s hard to shake off the slight feeling of cynicism that comes with anything that so closely echoes the beloved creators of Toy Story and Finding Nemo, but Henry does at least bring the invention of VR to the table. Imagine watching something like Pixar’s Presto, in which a magician and his rabbit come to blows, only feeling like you were really in the audience watching the mayhem unfold. Story Studio hoped this presence would help you grow a stronger bond with Henry.

The film doesn’t quite possess the intelligent story-telling techniques of its contemporaries, though. It’s somewhat clumsily introduced with narration from Elijah Wood, who lays out the story as photo frames appear from the dark. This feels like a piece that would have been more memorable without any spoken words; we could have sussed out Henry’s isolation for ourselves by spotting the clues dotted around his apartment. Self-discovery could be one of VR storytelling’s defining traits, and this fails to capitalize on that.

But, crucially, Story Studio was open and honest about its mistakes with Henry. As lonely as he might get during the film, he’d always shoot you a sad sideways glance, acknowledging your presence. That sort of meant that, really, he wasn’t alone; we were there with him. For Story Studio to really achieve its goals it had to exhibit what didn’t work just as much as it showed what did, and Henry definitely gave creators some pointers (pun intended) on what to avoid.

Dear Angelica

If you want to see how filmmakers can grow in VR, look no further than the journey Story Studio took from Lost to Dear Angelica, its final and easily most memorable piece. It was created with the Quill software that it would also release for free.

From the opening few moments it’s clear that Angelica is considerably more evolved than its predecessors, depicting a young girl recalling memories of her deceased mother via the movies she starred in as a successful actress. Scenes are painted into reality like a lucid dream, with elegant brush strokes that you can’t help but follow as they wind around you, slowly transporting you from the lonely confines of a bedroom to the fantastical sights and sounds of Hollywood, providing idealized metaphors for Angelica to be remembered by.

It’s a masterclass in using your imagination, blinding you with bold and brilliant colors, creating images you long to reach out and touch, and cleverly avoiding immersion-breaking clipping by having paintings fade the closer your head gets to them. If Lost shows you how cool it is to see big things in VR, Angelica teaches you about the intimacy of doing something much smaller. It’s most striking scene shrinks its characters down to a tiny diorama which you have to lean in to get closer to. This is some of the most intelligent storytelling I’ve seen in VR, successfully translating the tricks that traditional cameras can use to evoke emotion into fully fleshed out VR transitions. The movie tampers with distance and erratic progression in similarly affecting ways.

Dear Angelica is a lesson in throwing out conventions and forgetting the rules. Ignore what you know about capturing images on a flat rectangle; approach a story knowing the audience will be inside it with absolutely no preconceptions about how it should be told. Get creative; what does it mean if you’ve got so much going on the viewer doesn’t know where to look? Where can you go if you’ve got unlimited possibilities? How does it feel to have a character close to you? How does it feel to have them far away from you? Story Studio won’t want people imitating its creation, but it no doubt hopes to instill these same questions in the minds of its successors, and we’ll hopefully get better VR movies from that.

Oculus Story Studio’s untimely demise is one of VR’s most unfortunate stories so far, but co-founders Saschka Unseld, Max Planck and their team of creators should take heart in the fact that they taught the VR industry some valuable lessons to build on.

We often talk about how the VR rule book is yet to be written, and that we’re in the wild west of content creation. Story Studio played an important part in trying to tame those unknowns.