Sony has a gameplan for its attempt to dominate the world of virtual reality experiences: a pocket full of priceless film franchises and an online store full of eager virtual reality users. To Jake Zim, Sony Studios’ senior VP of VR, it’s a grand chance to live in those worlds, but as he later told me and as I quickly learned, Sony is first here to learn.

One of the studio’s early VR film outings, following The Walk and Goosebumps VR, comes in the form of the Passengers Awakening VR Experience, a roughly 20 minute exploration of what this medium could be. I awaken from one of the film’s stasis pods and an AI gets me situated with my VR body, which moves around using point and click teleportation. Once I make it out of the pod room, her guidance is quickly replaced by that of Chris Pratt, a swap I am perfectly content with.

Chris Pratt in the Virtual Flesh

He needs my help repairing something outside–something probably related to gravity or oxygen or a similar space problem. It is then that I begin my heroic journey of opening a series of hallway doors in order to reach Chris Pratt. To fix… maybe the hyper-drive?

Though his technical quandary may not have translated too clearly over my radio, Pratt’s voice acting is a delight, rather than a mishmash of quotes mined from the film. The actor was, as Zim describes, “totally gung-ho” about recording lines just for this project.

I pull lots of levers and open plenty of doors on my way, but every now and then a tougher door appears sporting a broken panel that needs my repairing. I set my multi-tool to the proper setting, and get to work tracing circuits, replacing broken parts, or turning valves to guide beams of light to their destination. The intent of these puzzle designs isn’t to keep me stumped or guessing, leaving things just simple enough for a human brain that’s been disabled in a pod for the last dozen or so years.

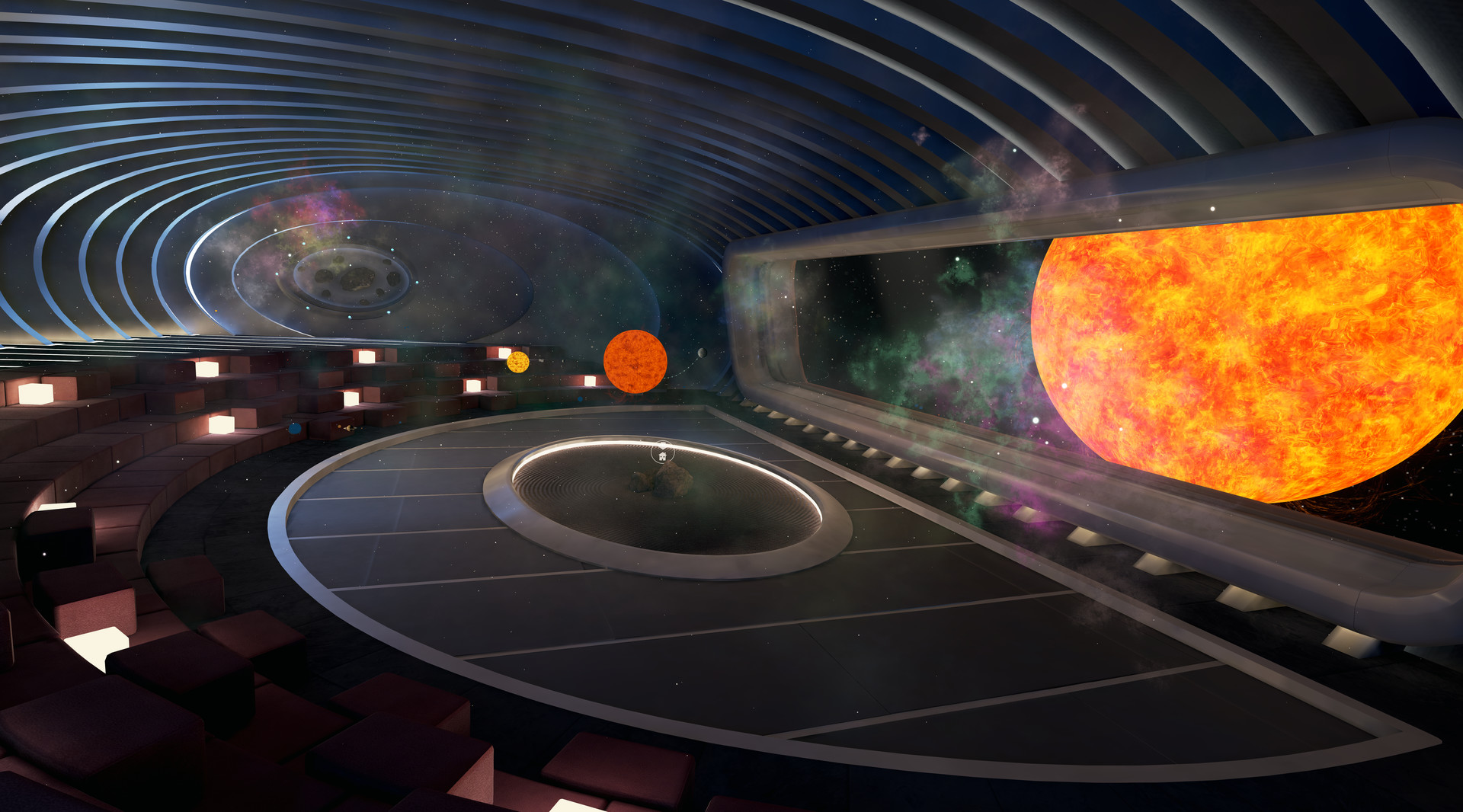

These challenges aren’t really meant to keep my attention, though; it’s this recreation of the film’s Avalon starship, a set so painstakingly crafted that Oscar-nominated production designer Guy Hendrix Dyas calls it the film’s “fourth character.”

Designing The Avalon

“For the interior I had a big concept that I wanted to try,” Dyas says of his work on the film, a rejection of history’s homogenous, sterile sci-fi ships. “It was either going to be a huge success, or I was literally gonna get chased down with burning flames by the science fiction elite.”

“My concept was, this is like a cruise ship. Why can we not have antiseptic, huge shopping mall spaces, and then when you go into, say for example the bar, why can it not be a 1920s art deco bar?” Dyas continues.

Entering each room of the VR experience is like peeling off another layer of Dyas’ atypical sci-fi imagination, one that poured out of him during the film’s almost impossible 10-week design frame.

“I’m a maniac,” he tells me as he recounts times spent with his sleeping bag in the office. “But the process of designing to me is so enjoyable, it really is the love of my life.”

The Avalon’s bar, upon entry, immediately abandons predictably white hallways and metal pipes. Warm brown wood and golden lights surround the film’s android bartender Arthur, played by Michael Sheen. He’s just so endearing that I have to put him to work, so I order a drink and watch him promptly ram his forehead into the countertop. Another malfunctioning puzzle panel pops out of the bar. Arthur was the real ‘boss’ the whole time.

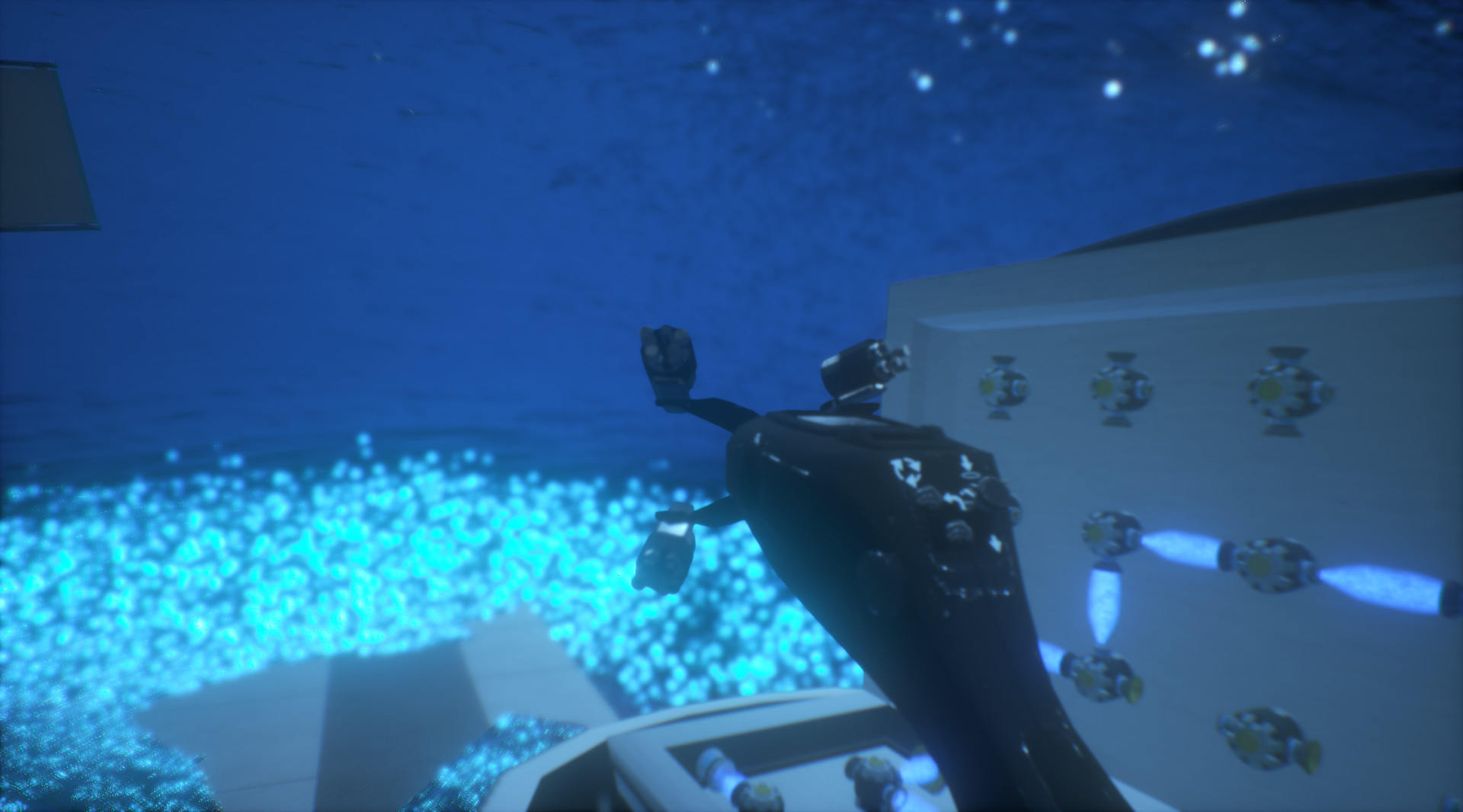

The second most memorable detour is the pool room, a place of sanctuary in the film for Jennifer Lawrence’s character. Dyas tells me it’s meant to evoke parallels to a famed painting of Shakespeare’s Ophelia, drowning in her despair. That impression is a little lost once gravity deactivates and the pool water becomes a mass of floating blue raspberry jello chasing me across the room. I play the Hokey Pokey with it for a while, dipping my head in and out of its sound-resistant surface, then continue onward.

Key points of interactivity and detail are sprinkled among the sets. Each of the 48 cryopods at the beginning have a unique name and background taken from someone who had worked on the project. In the observatory, Zim shares with me, players can find special audio tracks by sticking their heads into the holographic planets on display. The abandoned earth sounds like “cacophonous” crying, mining planets ring with machinery, and Homestead, the destination of these passengers, emits a jazzy Cantina bar tune. This Homestead planet in particular is too high up for any person to reach by standing. Players have to find something to stand on in the real world to shove their face into this easter egg.

Exploration peaks outside of the ship, under the visage of its massive, arching hulls. They’re sadly immobile, not the mesmerizing spiral of metal Dyas had designed, long ago inspired by falling Sycamore seeds outside his flat in San Francisco.

This area provides both the experience’s most provoking sights and challenges, becoming the most successful bite of immersion for Passengers Awakening VR. The looming ship arms left me gazing the longest, and some entertaining zero gravity physics finally bridged the gap between my actions and the specific world of Passengers in the way previous door puzzles did not.

The Future of VR Film Experiences

At the end of my day, I ask Dyas if he has tried the virtual reality experience, walked among his creation in another reality. His answer is confident: “No, I don’t need to. I don’t want to. I already did.”

In those words are Sony’s aspirations for this and future projects. Zim wants to pinpoint what in these worlds people are familiar with, what they love, and what the aspirational components are. Then he wants to submerge them into it, and see them move through as personally as its creator would. For Passengers, that key is its fourth character, a meticulous set prime for exploration and curiosity. Those sentiments evaporated slowly with each inane door lever, but piqued when I playfully discovered the bar piano was playable, and as I tried a dozen times to play zero gravity catch with Chris Pratt under the glow of the universe.

“We’re really proud about this project and we’re gonna continue to get better and keep optimizing,” Zim tells me. Passengers Awakening VR is available on Steam for the HTC Vice and the Oculus Rift for $9.99 (with a PS VR version on the way) and the team is excited to collect data on price point, length, and design before moving to deeper worlds. “We have to make stuff to learn about it and get the audience feedback.”

Sony certainly seems poised to learn, as Zim notes the roster of VR-eager studio talent and I glance at Dyas a few feet away. His world, passionate with a hint of rebellion, establishes a curiosity in VR, but that hook doesn’t consistently play off of the accompanying mechanics.

Zim and I spend a lot of time talking on the future. He tosses names from Sony’s wide catalog he’s inspired to tackle in the future hopefully, such as Karate Kid, Spider-Man, Jumanji, Lawrence of Arabia, Memento, and more.

“We can do all of that,” he says, filled with optimism. Should Sony adapt to the challenges of immersive VR interaction, supporting their studio talent with quirks and experiences more closely tied to these lovable universes, they can. Zim eventually wanders into thoughts of a Groundhog’s Day VR creation, with all the visible enthusiasm of a genuine fan, and I begin to feel more assured.