Never in a million years would I have wagered The Walking Dead would make for a great VR game. This is a brand, nay, an entire genre, that’s steadily slowed to a creative crawl, with seemingly every possible tie-in and conceptual angle hacked away at, sparing neither life nor limb. And yet, somehow, The Walking Dead: Saints & Sinners is a gory delight.

Skydance Interactive doesn’t owe its unexpected success to a piling body count or tough story-telling, but instead the rules its vicious world establishes early on. Moreover, it is the finely-tuned level of user interaction that rewards you for adhering to them.

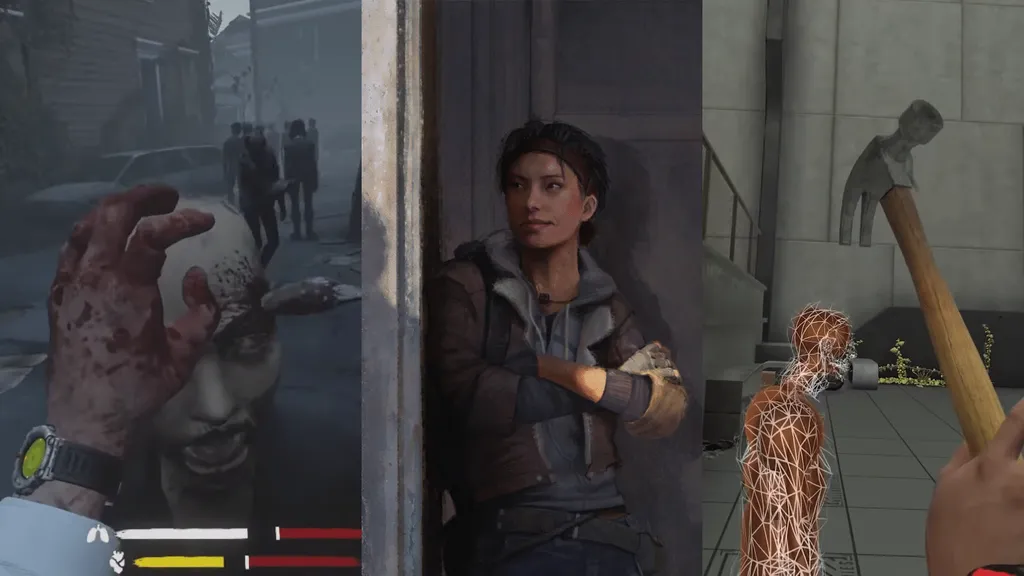

Like a growing number of VR titles, the Saints & Sinner’s experience is designed with physics and interaction at its very core. Need to stab a zombie in the head? You’ll have to properly thrust your blade into their brain with a disturbing degree of intention, not just waggle a stick in their direction. Nasty cut need healing? Grab a bandage and physically wrap it around your arm to patch yourself up. It turns a traditionally trite mechanic into an entirely new experience, one that seamlessly splices its way into the pressured world of survival horror inventory management like never before. It proves to be far more compelling than it has any right to be.

Ten minutes of holding off the hordes, and it is tough to go back to the feather-touch feel of older VR games. Dual-wielding pistols don’t carry the same sense of heft, and can be aimed and fired like they’re balloons. Axes and swords phase through enemies as if they were made from thin air. Perhaps most damning, monsters and foes can grab hold of you, but you feel powerless to properly shove them away. But here, you have a physical presence, one that demands a higher degree of real-life imitation than has been asked of us in the past.

This isn’t a new concept, of course, but it is evolving. Free Lives’ Gorn, RUST LTD’s H3VR, and WarpFrog’s Blade & Sorcery arguably started us down this path. Gorn, for example, earned scores of sales for its slapstick, uncompromising violence and Blade & Sorcery did the same by delivering the most satisfying melee action yet seen in VR (or, to face the uncomfortable but more telling truth, providing the most realistic stabbing you’ll find in VR). Hot Dogs, Horseshoes and Hand Grenades (H3VR), meanwhile, avoids the violence issue by making its enemies hot dogs while growing a significant audience by continually refining and expanding what ends up being an enormous physics-laden playground. But it is 2019’s Boneworks that serves as the real poster child for this new style of play; a game obsessed with the minutiae of reloading a gun. In this physics funhouse every enemy must be grappled with and, most impressively, every puzzle solved with a genuine injection of player invention.

Crucially, though, this fledgling approach to VR design is anchored around one of the core tenants that makes this technology so special; it makes you someone.

In Boneworks, it transforms you into a sort of gun-slinging Superman; enemies are mere toys to be ruthlessly experimented on. For Blade & Sorcery, you become the brutal, elitist gladiator front and center of a summer blockbuster poster. In The Walking Dead, it makes you the idiot you laugh at in zombie movies, the one making all the mistakes you swear you’d never make. It is the true embodiment of, well, embodying someone else.

Hurdles remain, of course, all of which are equally important to somehow pull yourself over. The Walking Dead and Boneworks offer compelling evolutions over Gorn and Blade & Sorcery, but neither is perfect, often content with letting sandbox-style carnage fill in for a lack of more decisive campaign design. Boneworks in particular never fully escapes the shackles of the hugely promising technical demonstrations it started life as.

We’ve got our tracked fingers crossed that Half-Life: Alyx serves up the next step in this journey. Valve’s Source engine broke ground with its physics-driven breakthroughs, but more importantly, its creators gave these inventions context. It took its stunning foundations and made them a living, breathing feature inside an otherwise excellent shooter.

Even Alyx, though, isn’t coming to the most important VR headset on the market: Oculus Quest (at least not natively, it isn’t). The games we’re talking about here push the processing power of PC VR gaming to the max with their complex systems. Quest, by comparison, is running smartphone-class processors and that means the jury is still out on whether Facebook’s standalone system will be able to handle these significant innovations; the upcoming port of Saints & Sinners and the spin-off Boneworks game will likely be the judge of that, but translating the satisfaction unlocked by these PC VR games to standalone VR will be vital to keeping that content library fresh in the years to come.

There is, of course, the matter of what happens when this devilish level of violent detail reaches the masses, though that’s perhaps a topic best saved for another time.

But it is here where you see VR gaming that’s truly native to headset and headset alone. True, you could play Saints & Sinners with a pair of Move controllers on a PS4, but I’d guarantee the loss of depth perception and enemy proximity would make for a painful translation. Without a VR headset, it would be virtually impossible to negotiate your way through most of Boneworks’ minute interactions.

VR headsets might not have moved onto a true ‘next generation’ of products yet but, remarkably, VR software seems to be getting there without the leaps in fidelity and control we’ve come to expect from successive hardware. That suggests that, by the time PSVR 2, Rift 2, Index 2 and others are ready for the limelight, we’ll finally have a gaming ecosystem that’s figured itself out. Quite an exciting thought, that.