Archery game QuiVr recently emerged from Early Access after more than two years of development. During that time, the game sold roughly 35,000 copies on Steam.

Sole programmer Jonathan Schenker and business partner Aaron Stanton say the game, selling at $20 per copy, generated around $700,000 in gross sales before Valve took a 30 percent cut for the Steam store. Stanton assisted with the design, business development and marketing of the game and the two split a $30,000 investment in the project to get original art made for QuiVr.

The game failed to achieve the same sales milestones as other indie VR games like H3VR and Beat Saber, each selling 100,000 copies at the same price as QuiVr. H3VR is an experimental shooting game which achieved that milestone between 2016 and 2018. Rhythm slashing title Beat Saber achieved the same milestone in just one month of 2018. There are also a lot of developers who have struggled with their first generation titles selling well below QuiVr. I hope to talk with more developers to tell those stories too. For now, I’m sharing what Schenker and Stanton explained over email about how they achieved a “reasonably profitable” approach with QuiVr.

‘A Hobby I Thought Was Cool’

According to Schenker, in May 2016 he was finishing up a computer science degree which he got “by convincing professors to let me use Unity to complete projects.” He also participated in hackathons and game jams during his free time. Schenker tried the HTC Vive at GDC and watched early development videos put together by H3VR developer Anton Hand. Schenker used to be into real-life archery and didn’t know Valve’s The Lab had its own archery game when he started prototyping another one in the Unity game engine.

“Before Aaron joined QuiVr was really just a hobby that I thought was cool,” Schenker wrote. “I had a full time job as a web developer and was happy just working on my archery game on the side with some feedback from the VR early adopters on Reddit and Steam.”

The first time Stanton played the game “you could download the demo, launch it, shoot one guy walking across the screen… and then you would have to quit the game, and restart it, because there was no respawn mechanic.”

“Without Aaron’s push toward tackling development with more of my time and effort, I’m sure that QuiVr would have spent much more time in Alpha before going into Early Access,” Schenker wrote. “I really just like making cool stuff and sharing it with others, Aaron’s involvement played a key role in convincing me that it was really worth pursuing as my primary focus.”

Stanton also suggested they get “help with outsourcing art.” That step was critical in turning QuiVr “from a generic fantasy game into a game with its own story to tell,” according to Schenker.

Stanton reached out to arcades as well by offering a licensed version of the game to deploy in locations around the world, adding more revenue to their effort. Stanton previously founded a startup called BookLamp which was acquired by Apple, where he worked for several years after Apple bought it. He says that experience “prepared me for this sort of work. In fact, there’s a part of me that feels that my start-up experiences were training grounds for helping me be in a position to help the VR and AR industries establish themselves, now.”

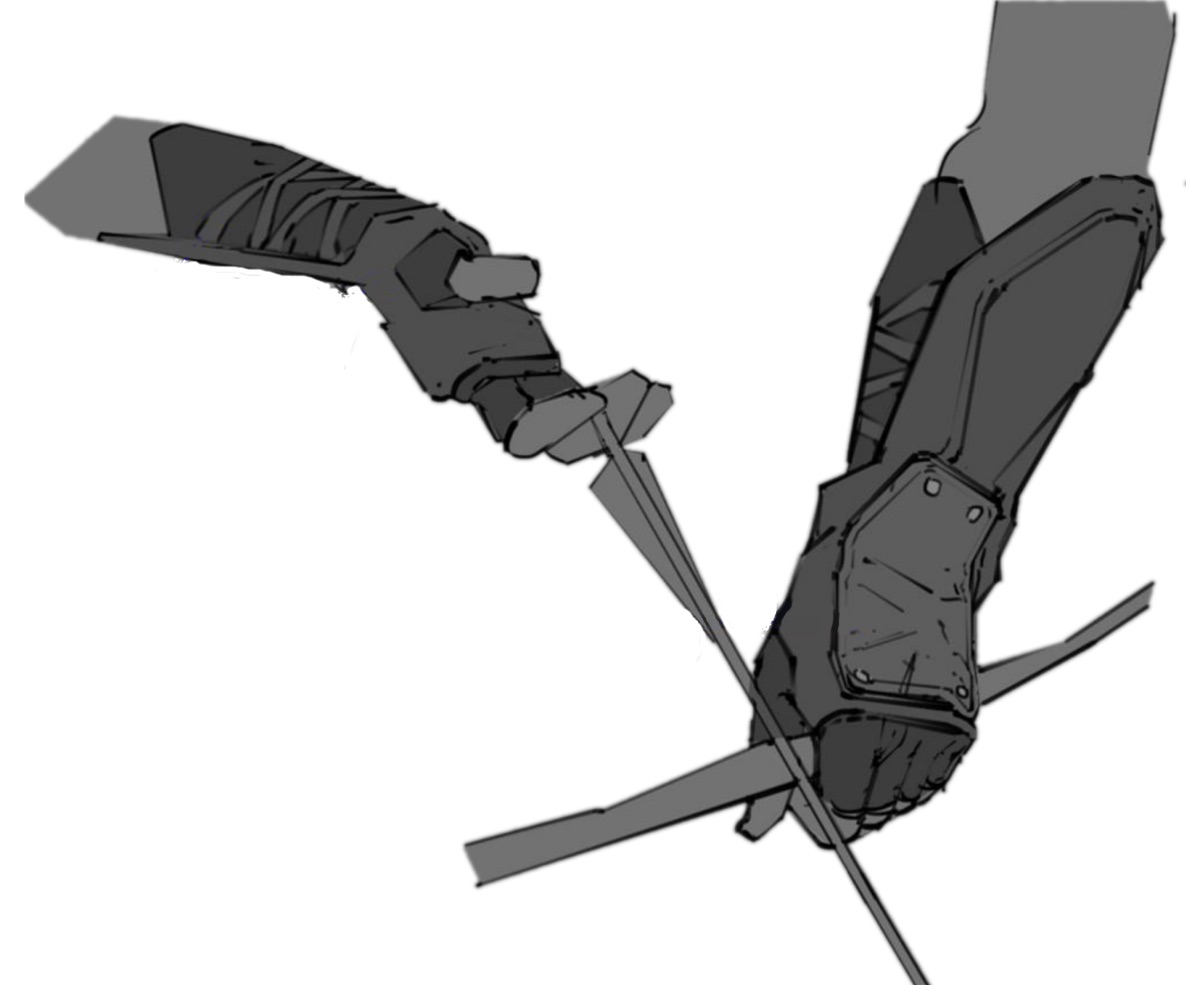

Stanton said he thought, based on the QuiVr demo, that “the core of the game was amazing. The mechanics for the bow and arrow felt soooo satisfying, and Jonathan’s openness to the community was like nothing I’d ever seen before. Not only did he listen supportively of almost every piece of feedback he got, but he implemented much of it that same day, and sometimes within hours. Someone would suggest an idea, and almost immediately an update would come out that incorporated the feedback. I really enjoyed both the foundations of his game, and also the way he listened and was transparent with the community.”

Setting Expectations

Stanton reached out and introduced himself and the two began working together about a month later.

“One of the first things that we did when we started working together is analyze other games on the market, and compared them to the traction we were getting in the demo,” Stanton wrote. “We created a number of spreadsheets that modeled potential revenue at different price points, and then plugged the numbers of a bunch of different games into the sheet. We used data from SteamSpy at the time to estimate sales compared to price. Essentially we did an analysis of the competitive landscape. We identified games that we felt had a similar scale and community, and then clustered them into groups: All the games similar to us at price point A, then price point B, then C, etc.”

“We decided at the time that we could be very confident based on the traction of the demo that we’d sell between 2,000 and 6,000 copies at the $19.99 price range. At the time we were still using only assets from the Unity store, and we were trying to decide how much money we wanted to spend to create custom graphics, etc. The conclusion we came to was that a $30,000 budget and investment in the game’s art creation would almost certainly pay off.”

Investing In The Project Together

They split that investment right down the middle but Schenker remains the dominant partner. Stanton is also careful to note the analysis he shared is “old now, since it was done more than a year ago, and also took into account the traction we already had from working on the demo.”

“The intent was always to be extremely conservative with what we were targeting for sales,” Schenker wrote. “I distinctly remember a conversation where 10,000 units was our ‘very successful’ mark. The budget was intended to be fairly lean so that failing to sell well wouldn’t be too serious of an issue and would just mean that our strategy for the next game might look a bit different.”

The game was updated several hundred times over the next few years and there are nuggets on Steam page offering insight into Schenker’s perspective as the project evolved: “I had dreams about maybe working in the game industry…Over the next few months, QuiVr is going to do quite a bit of ‘growing up.’”

Design Document And Planning

One key to QuiVr’s development was an 18-page design document they put together and shared in October 2016. Based on their traction from the free demo and their competitive analysis, they made a plan to lay out for potential buyers before the transition from testing release to Early Access.

“It’s important that the scale of a project in VR match the likely returns,” Stanton wrote. “You have to be able to be happy and excited about a modest return early in the VR space, or you’ll burn out before the mainstream really arrives. If you’re spending more than $10 to $15K on a VR experience without some additional reason to believe that the game will get traction (i.e. you have brand awareness, early feedback from consumers from a demo, etc) then I’d encourage you to scope and release what you can in a much faster and smaller basis, and then ramp after you’ve been able to judge initial traction.”

“The team has to be motivated by a love of gaming, of exploring new spaces and things – that generally means that the developers have to be the direct owners,” Stanton wrote. “They will then stay in the game long enough to be positioned well when the market reaches critical mass, either in VR or AR.”

Early Access Launch And Sales

On the day of QuiVr’s Early Access launch in December 2016 they sold 818 units.

Sales settled down to around “100 a day for a number of months, now over a year and a half it’s around 15-20 a day during the off times with spikes of 150+/day during sales,” according to Schenker.

“We’ve found that it’s better to optimize our releases and sales for the major Steam holiday sales. Our daily sales are fairly constant, but the spikes we see around things like the Summer sale are what drive the majority of proceeds,” Stanton wrote. “We have a bit of an issue (that we created ourselves) in that we release so rapidly that even big updates don’t really have a ‘promotion event’ – we don’t send out press releases or announcements when we push major changes. Now that we’re out of Early Access, we’ll probably begin bucketing our releases a bit more, and so that might change.”

Multiplayer

One of the defining features of QuiVr is its multiplayer, a feature which was forced to overcome a huge hurdle in the first two years of consumer VR headset availability. While some developers have been able to carve out a way to support themselves during the first few years of consumer VR, multiplayer games have been a tough sell because there are so few headsets in the market. At any given time the people in VR are split across dozens of different virtual worlds. So it can be hard to find people to play with in any single virtual world.

“I’ve repeatedly seen other games come onto the market trying to do PvP gameplay, which is great, but without an existing user base, even very good games struggle because you can’t find people to play against,” Stanton wrote. “QuiVr has the principle of ‘Cooperative Independence’ as one of our core design principles, which basically means that we want multiplayer, but that one person’s skill (good or bad) does not interfere with another player’s ability to enjoy the game. Then, we have drop-in multiplayer — essentially, if you join multiplayer, and there’s one other person in the world playing, you’ll have someone to play with.”

Building A Healthy Partnership

Schenker and Stanton say that aligning their goals was key to their partnership working, combined with respect for each other’s strengths and clear communication.

“Alignment of goals is important. Both Jonathan and I have very similar outlooks on the industry, and what we hope to accomplish,” Stanton wrote. “While Jonathan and I both have strong opinions about things, and mostly agree, if we were not to – the QuiVr brand is Jonathan’s brainchild, and my job is to help it and him be as successful to his vision as we can be. In other projects I work on, it’s important to me that I’m king and can own the decisions that are made. But with QuiVr, it’s important to me that I am ok letting his judgment trump mine, even in areas that I disagree. And once a decision is made, to do my best to make it successful whether I think it’s the right path or not. Both partners have to be open to the possibility of being wrong, constantly.”

“Communication is the key to any relationship, business or otherwise,” Schenker wrote. “I was very moved by an old GDC talk given by Sid Meier about taking and using feedback, which has affected how I interact with everyone when discussing how to improve the game. One of the key points was to never dismiss a criticism or suggestion, as having someone go out of their way to ask you a question or suggest something means that they actually care about the game. So whether it’s Aaron, or a family member, or a new player giving suggestions or feedback, I always try to take the time to absorb what they are saying and have an full conversation about costs, benefits, trade-offs, etc. It’s important to know where your strengths and weaknesses are so that you can know when your opinion should be weighed more heavily and when your ego should take a back seat to someone else’s logic.”