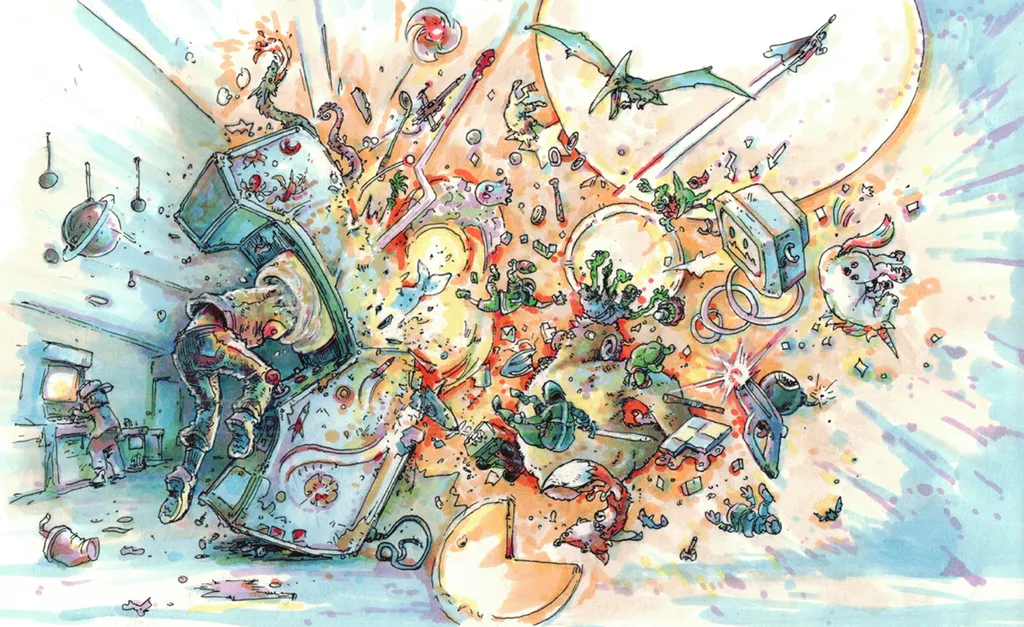

Once upon a time, in the middle of the night, there was a restless man pacing a residential street with a yellow tape measure in his hand. To the untrained eye, he appeared to be alone—some sort of compulsive insomniac bent on determining odd distances—but throughout the night he was kept company by visions of goblins, wizards and other enchanted creatures.

Like the protagonist of most fairy tales, if this man were to be evaluated mid-story he’d be deemed foolish, naïve or perhaps even insane. Interview Jack as he climbs up the beanstalk, and he’s a poor barterer ascending to god-knows-where. Poll Pinocchio as he arrives at Pleasure Island, and he’s the poster child for idealism run amok. That’s just how it is, and how it’s meant to be, because like most things in life fairy tales are a results-oriented business. The man with the tape measure knows this, but still he will persist. That’s because despite the stakes, and the dangers of embarking on destination-defining journeys, attempts at happily ever after are made just about every day.

This is a story about three such flights of fancy. A trio of ventures—one in Seattle, one in Utah and one all the way in Sweden—who are not only trying to find success in pair of industries that supposedly died in the 90s, but whose recipe for doing so it based on combining those two thought-to-be-dead things: arcades and virtual reality.

Part 1: Just a Bunch of Kids

“The idea started back in 2010,” begins Jamie Kelly, co-founder and president of VRcade, a Washington-based entertainment company responsible for the world’s first full-motion virtual reality arcade. “But, at that point, we didn’t want to call it VR. Because virtual reality was just this kind of discarded mistake from the 90s.”

So Kelly stayed away from any association with VR though, by his own admission, the original incarnation wasn’t even really virtual reality. The initial idea that Kelly posed to co-founder Mark Haverstock was to create what amounted to Laser Tag 2.0. No headsets, no pixelated realms, but rather focused on crafting a uniquely malleable arena that could be programmed to somewhat mimic videogame worlds.

“I wanted to build a room that had one foot by one foot squares in it,” recalls Kelly. “But these squares were actually the tops of columns—attached to pistons below—which could change elevation based on programmed commands and could be used, essentially, to terraform all sorts of different real world environments. Basically, I wanted to create a version of Halo or Call of Duty in real-life.”

If you can’t visualize exactly what this might look like, think of as something like a real-life version of the X-Men’s Danger Room. Or don’t bother thinking about it, because eventually that’s what Kelly and Haverstock had to do. There were too many logistical issues (like price, safety and objects getting lost in the transformation) as well as problems associated with this not actually being a videogame (such as being able to equip players with a map of this volatile terrain).

Even so, they were still interested in exploring some version of this idea: maybe the room didn’t need to transform, but instead players could wear glasses or a head mounted display that transformed the room. So they sought advice from a computer scientist friend (and future VRcade co-founder) Dave Ruddell. After initially nixing the idea, he grew more and more fascinated by the challenge—to create the real-life equivalent of a videogame that could be played together by friends—which, along with some breakthroughs in positional tracking, inspired the three guys to keep forging forward.

“And so for two years,” Kelly explains, “it was just whiteboard arguments about what will or will not work. How do you track a user? What will cause the most latency? Meanwhile, we were talking to everyone from these people who make magnetic tracking to the people who track NFL players on the field. But none of them had the ability to track with the level of precision we needed. And the prices were just astronomical.”

Given these seemingly unsolvable challenges, the guys had just about given up. Until one evening, very late at night, Kelly stumbled across some interesting information online: NaturalPoint, an Oregon-based company that specialized in optical tracking solutions, had just announced the release of their Prime 41 camera. Billed as the “largest volume motion capture camera in the world” and requiring no more than a perimeter-only setup, the Prime 41 claimed an ability to capture space of 75 x 150 feet.

Inspired and incredulous (as well as not quite sure how big 75 x 150 feet really was), Kelly grabbed a tape measure and took to the street at around 2 AM. “Okay, this is big enough,” Kelly remembers with excitement. “This will totally work for 8 players and we can make crazy content for this space. So we got in touch with NaturalPoint and asked if the tech really worked as advertised, if we could really scale it that big and all sorts of other questions. Yup, yup and yup. So that was amazing, but then we still had one big problem: we couldn’t afford any of it.”

This is where luck (and misfortune) met opportunity. In May 2012, Mark Haverstock’s grandfather passed away. Not long after, Haverstock’s father inherited some money, and not long after Haverstock blurted out what he thought might make a good investment.”

“You should invest in my company!” Kelly recalls, and then laughs. “We weren’t even really a company at that time. We were just a bunch of kids. But his dad saw what we were doing and got really excited.”

Seeded with enough funds to finally give this thing a go, the guys were able to purchase the tracking equipment that they need. And in another fortuitous twist, the company Kelly worked for at the time had just acquired a floor in a rundown building that was going to be torn down and rebuilt. But that wasn’t going to happen for six months, so they let him and co-founders set up shop in there. They set up cameras around the dilapidated space, wired up a pair of Vuzix video glasses and Ruddell wrote a program that enabled them to test it all out.

“The field of view was crap,” Kelly remembers, “and it was wired, but the fact that when you moved you were tracked in this big space, that was unbelievable. And it grew to: now we can attach markers to a shotgun, now we can pull the trigger and send a command to the game engine to fire a laser. Oh my god, we’re able to shoot targets.”

With former fantasies now readily within grasp, everything evolved in this fashion. The Vuzix video goggles became a homebrewed pair of suped-up ski goggles, the tangle of cords was replaced by a wireless video module, and years after the supposed deaths of both arcades and virtual reality, the guys were shooting zombies in their makeshift VRcade. This thing was awesome—no, it was absolutely amazing—but it was an amazement enjoyed solely by these three (and whoever they’d bring by for a demo) unless they could figure out a way to scale it.

Part 2: The Magician’s Dream

James Jensen had big dreams, but he knew well enough not to spring them on Ken Bretschneider and Curtis Hickman right away. Especially because Bretschneider and Hickman were in the middle of some big dreams of their own: a 45-acre, $100 million ever-changing, interactive theme park called Evermore. Although the park would be located in Utah, its fantastical technology promised to usher patrons back in time to Victorian England.

“I actually found Curtis and Ken through LinkedIn,” Jensen explains. “They were looking for a guy to do previz for their theme park. So I came on board and brought some of the game developers I was working with at the time and we created an iPad app that would allow investors to walk through what Evermore would look like. And, well, I got involved with that project knowing that I was eventually going to spring this idea on them: of mapping a virtual world over a physical world.”

It’s hard to say when Jensen had come up with this idea himself. With a deep background in visual effects, motion capture and graphic design, he had been toying with the idea for over a decade but only just starting to believe—especially after seeing Oculus’ head mounted display—that the technology existed to effectively bring his dream to life.

After capturing the interest of the Evermore guys and convincing them that this was really, truly possible, Bretschneider put in $250,000 so they could develop a prototype. “I knew the limitations of optical tracking,” Jensen recalls, “so the first prototype I put together was actually with an electromagnetic field generator system. But that system had its own inherent problems. It had warping on the edges. I know there are people out there experimenting with that right now—electromagnetic systems—but it’s just a box of terror. It’s a pain. So that didn’t work out very well, and we switched back to an optical tracking system for a while.”

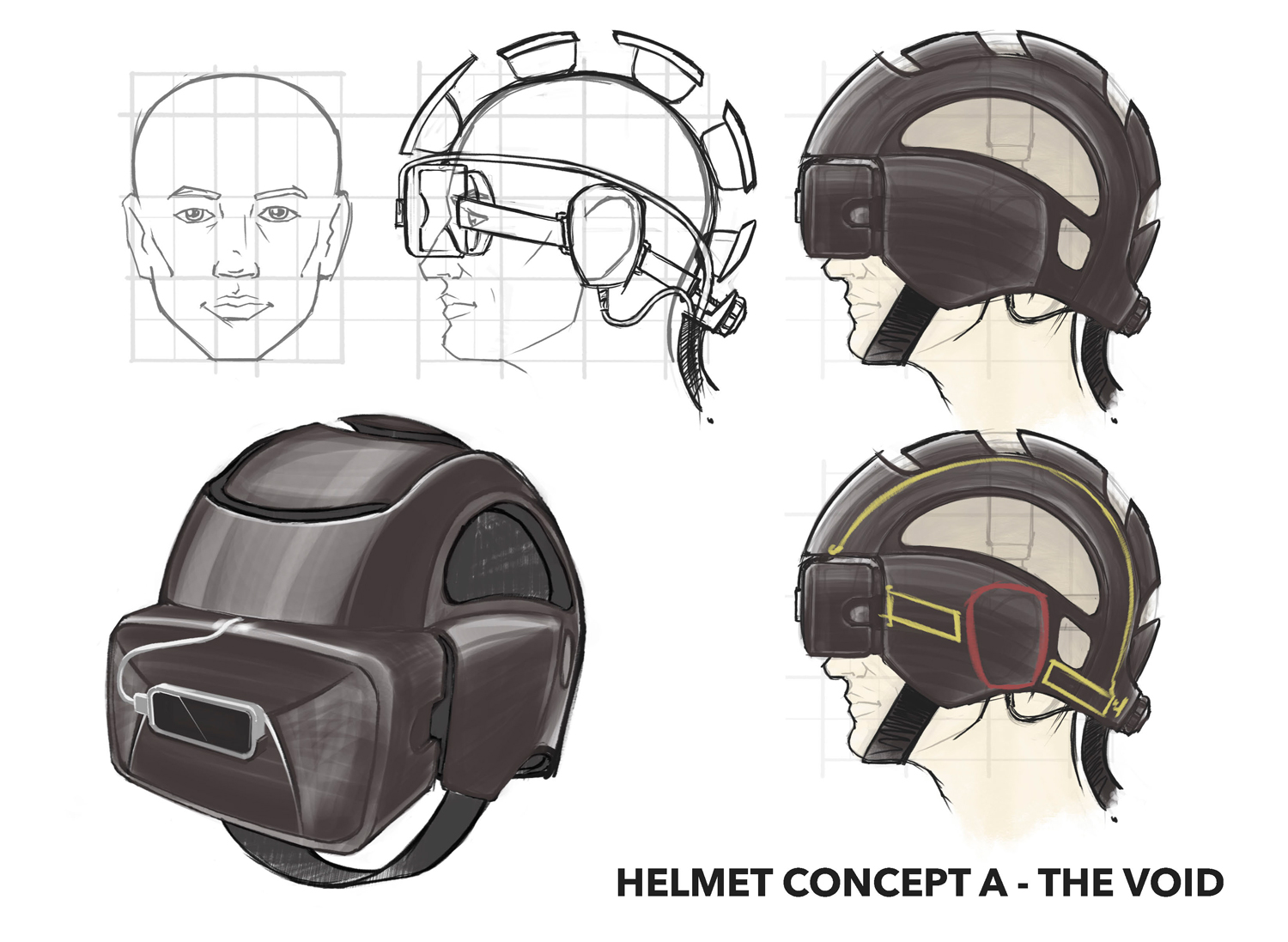

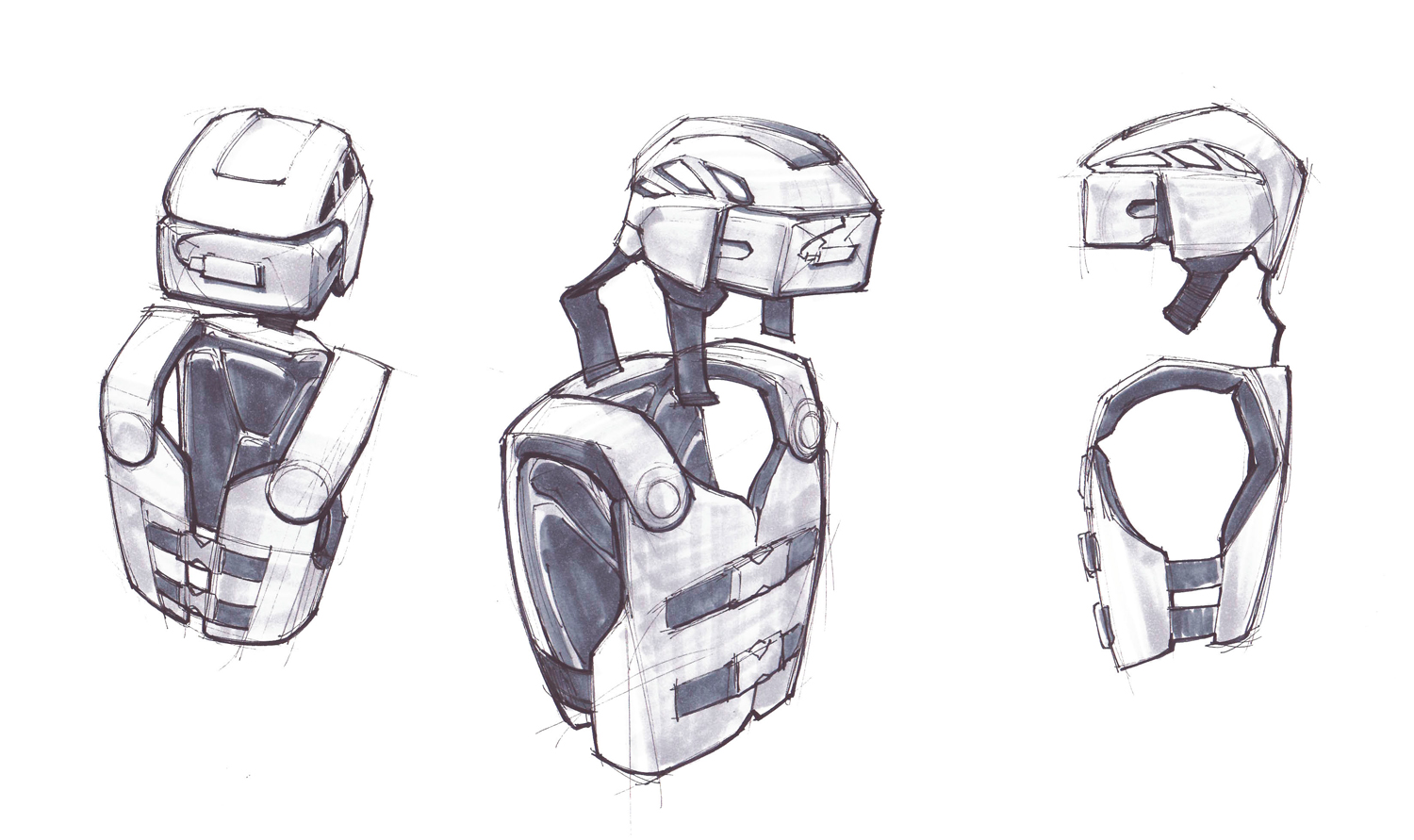

Although the optical tracking system wasn’t perfectly ideal (the guys still uses an iteration for demos, but recently brought on a nuclear engineer to build a new system based on radio frequencies), the tracking on their prototype was enough to successfully demonstrate that this thing would work. Which, of course, begs the question: what the heck is this thing? VR? AR? Laser Tag 3.0?

We’ll get to that shortly, but before addressing the what, it’s imperative to first consider the who and the how. That’s because the guys who Jensen co-founded this company with didn’t come from any tech industries. Hickman had a background in magic and illusions, having previously worked with both Criss Angel and David Copperfield. “So when I told Curtis that he’d have full control of our users’ eyes and ears—and everything they touch and see—he was like: oh my gosh, this is a magician’s dream.” Bretschneider had his feet planted in a few different worlds through the three companies he had previously founded: DigiCert, an SSL certificate provider, People Water, a philanthropic venture and Deep Studios, a full service production studio. Most importantly, however, Bretschneider understood the impact of storytelling on experience. He’s the one who actually concepted the idea behind The Void’s brand. And that’s the how. That’s a big part of what the company believes differentiates them from just about anything else on the entertainment spectrum.

Part 3: D&B

Unlike The Void, with its amusement origins and narrative-focused experiences (more on that later), VRcade differed in that—at least initially—they viewed themselves as more befitting more of a traditional arcade model. As such, they were looking for a series of locations where they could try and grow their full-motion gaming platform to scale. But in an era where the power of consoles increasingly trumped the potential of co-operated games, finding such a venue was no easy feat.

Enter: Dave & Busters. Since founding their first restaurant/arcade in 1982, the Dallas-based duo of David Corriveau and James “Buster” Corley had opened over 70 more locations around the country. Though Dave & Buster’s touts itself as the “only place to Eat, Drink, Play and Watch Sports!” most people—or at least those of us above 30—know D&B best as the “only place where you can play arcade games like we used to do as kids.” Which made it even more of an ideal target for VRcade’s Seattle-based thirtysomethings.

“Dave & Buster’s was perfect,” Jamie Kelly says. “And they had been experimenting with VR for a couple of years, knowing that they needed some kind of draw to get people in and stay on the cutting edge.”

In the spirit of that experimentation, Dave & Busters partnered with VRcade to test their wireless wares this past July. Stationed near the entrance to D&B’s location in Milpitas, California, visitors were immediately greeted by a black, aluminum structure—about 12 feet tall and 15 feet wide—where, for five dollars, players could don a headset and try to shoot their way to safety in a game called Time Zombies.

“At first, nobody knew what this thing was,” Kelly recalls, “But as soon as one person got in, people would stop and watch. And then the person in the game would start freaking out; they’d start screaming and swearing—even though they were in public—and more people would gather to watch this person freak out. Then finally, the person would come out, and they’d have this oh-my-god moment. That was the greatest thing I’ve ever done! And as more people played, more people stopped to watch; it was just this great snowball effect.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the VRcade guys had expected to attract certain type of demographic: basically themselves, twenty years ago, when they used to roam arcades. But it ended up attracting an audience of all ages, genders and races. Which, along with its financial intake, explains why Dave & Busters is currently continuing to test VRcade systems at various locations around the country. Interestingly enough, they won’t release those locations in advance because they want to see how well the setup does without any advertising.

“So we’ll see how it goes and take it from there,” Kelly explains, hoping that the snowball effect he saw in store will bear out on a national level. But regardless of if or when that ends up happening, the Milpitas test holds its own intrinsic value. A validation and legitimatization of a project that so often felt destined to faith. But they did it, just a bunch of kids from Seattle, and grew even more powerful by what they learned from that initial test. “There are just so many questions to answer when you’re building an out-of-home virtual reality experience and we answered a ton of them.”

Part 4: Data Detective and the Quest to Uncross the Stars

“There is still a lot of research to figure out in order to make the best VR experiences,” says Maeva Sponbergs, the Head of Operations and EVP of Communications at Starbreeze. Though it’s important to note that even as she says this—even with that clack of cautionary italics—she couldn’t sound more optimistic about the future of virtual reality. It’s also important to note that she didn’t always feel this way.

In early 2015, Starbreeze’s CEO Bo Andersson surprised his employees by announcing that the company would be betting big on VR. Instead of receiving a roomful of applause, his was greeted with what could most generously be described as upbeat confusion. “I wasn’t a believer at first,” Sponbergs recalls. “You can’t help but go: uh, okay, I remember The Lawnmower Man. But you’re very careful about telling your boss that you don’t think this is a good idea. Especially when you all love and respect that boss very much.”

Like many employees, Sponbergs’ upbeat confusion lasted until she sat in a wheelchair to demo an experience based on The Walking Dead and blasted her way through an undead virtual world. That was the first time she felt her brain and body were in tune—when it “really clicked in my brain,” as she describes—and from that moment on she was convinced. Which meant that now, as a true believer, it was her job to pay that feeling forward; not only through the software that Starbreeze was and would be creating, but also—via an important acquisition—through a hardware device as well.

In June 2015, Starbreeze acquired InfinitEye VR—a French company who, since 2013, had received attention for its 210-degree HMD prototype—for $2 million. Just days after the deal was announced, Starbreeze introduced their new StarVR headset at E3 with a custom The Walking Dead VR experience. Following E3, Starbreeze continued the momentum by launching an RV tour that brought demos of the game to San Diego Comic Con, Walker Stalker, Pax Prime and other similar conventions.

“The biggest surprise from our RV tour,” recounts Sponbergs, “was that People wanted to come back and do it again and again and again and again. And we learned a lot; about managing big crowds, getting people safely in and out, and about the VR experience itself.”

In fact, Starbreeze found what they learned to be so valuable that it helped spearhead their decision to launch a virtual reality arcade later this year. Tentatively named “Project Starcade,” the upcoming entertainment initiative is expected to launch in Los Angeles in the spring or summer of this year. “It’ll probably be called something else when we open shop,” Sponbergs explains, “but the general idea behind it is basically to be able to collect more data. We haven’t announced a release date for our headset yet, nor our experiences. So I would say that this is more for us—for learning—and spreading the gospel of VR in general. Because if you haven’t tried VR, you have no concept of it, right? And I haven’t seen anyone skeptical after spending some time in VR; seeing that reaction it really gives you that checkmark: yeah, this works; yeah it really does.”

Part 5: A Fairy Tale for the Digital Age

“It works!” James Jensen excitedly recalls, describing one of The Void’s early benchmarks, where he and his colleagues managed to turn a bland basement into an elaborate space station. “It was a completely untethered experience. And you could touch a few walls that existed no matter where we went. It was awesome.”

One of the reasons it worked was because Curtis Hickman had created a key stage illusion that made it all possible. A proprietary redirected walking technique that Hickman calls it the “Infinite Hallway.” It solves virtual reality’s throughput issue and enables The Void to create infinite worlds.

Which enables The Void to achieve its ultimate objective—something that goes beyond the images and emotions associated with words like “virtual reality” and “arcade”—and transport users to a parallel world. All it takes is a headset and a lightweight backpack (equipped with customized computer) and then, with the flick of a switch, voila! Suddenly you are elsewhere.

It’s amazing, it’s intoxicating, and it’s sci-fi come to life. But, superlatives aside, it also inspires a pragmatic question: How do Jensen, Hickman and Bretschneider entice the masses to visit audiences to visit their infinite worlds of elsewhere?

Read More: Moments of True Presence: We Step Into The Void

Like the fairy tales of yore, and like this article you’re reading, The Void is counting on the power of story to relay a larger message. “Story,” Jensen reiterates. “It’s what people get emotionally tied to and excited about it.” But he isn’t simply referring to the story aspects of a game, experience or unique interaction. He’s reverse-engineering entertainment back to its narrative foundation: backstory. And that starts, first and foremost, with The Void itself.

“Tracy Hickman is on our staff,” Jensen explains, referring to the 14-time New York Times bestselling author, who is also the father of co-founder of Curtis Hickman. “He’s writing a whole backstory that starts in the late 1800s with a group of that breaks off from Tesla and starts opening portals to parallel worlds. Long story short, all that technology gets passed down from generation to generation—used in things like videogame development and particle effects—kept away from the masses until now, when we finally have the technology to do this on our own without people going insane. So there’s this whole big story, which is almost like a meta-game over all our experiences, and there’s an online component as well.”

If all this sounds a little distant from arcades, games and virtual reality then, well, mission accomplished. In a way, that’s kind of the point.

Part 6: In Which Three Stories Become Part of a Large Narrative

James Jensen: We’re kind of even kicking the term “virtual reality” to the curb because we want to bring people to new worlds. What we’re doing is more like a parallel world, because it blends together the physical world with an imaginary one. Whereas virtual reality, from what I saw that was being released, was really like glorified 3D movies. You couldn’t do what everybody really wanted to do, which was walk around and go explore, you know?

James Jensen: We’re kind of even kicking the term “virtual reality” to the curb because we want to bring people to new worlds. What we’re doing is more like a parallel world, because it blends together the physical world with an imaginary one. Whereas virtual reality, from what I saw that was being released, was really like glorified 3D movies. You couldn’t do what everybody really wanted to do, which was walk around and go explore, you know?

Jamie Kelly: You need to be able to move; to run and jump and kick and punch and hide and stay still and hold your breath. And the technology that would allow that to happen is so expensive. But by putting it all out of home, there’s a way for people to essentially rent it and get an experience that is better than anything they could get at home in this incredibly immersive way.

Jamie Kelly: You need to be able to move; to run and jump and kick and punch and hide and stay still and hold your breath. And the technology that would allow that to happen is so expensive. But by putting it all out of home, there’s a way for people to essentially rent it and get an experience that is better than anything they could get at home in this incredibly immersive way.

![]() Maeva Sponbergs: The immersion is everything. It’s about actually being able to fool the brain. And, you know, the backbone of Starbreeze is in games development. That’s always where we start when we want to look at a project. And so we need to collect feedback from users in order to provide the best experiences.

Maeva Sponbergs: The immersion is everything. It’s about actually being able to fool the brain. And, you know, the backbone of Starbreeze is in games development. That’s always where we start when we want to look at a project. And so we need to collect feedback from users in order to provide the best experiences.

James Jensen: It all really comes down to experience. That’s what people want nowadays. Like people aren’t satisfied with the normal movie experience any more, they want more. They want an IMAX theater, they want cushy chairs; they want a heightened experience. But the social part of a theater is really not going to go away. Everybody wants to go out with their buddies and do something.

James Jensen: It all really comes down to experience. That’s what people want nowadays. Like people aren’t satisfied with the normal movie experience any more, they want more. They want an IMAX theater, they want cushy chairs; they want a heightened experience. But the social part of a theater is really not going to go away. Everybody wants to go out with their buddies and do something.

Jamie Kelly: Even in this generation, people still like to get up and go places. For me, growing up, that place was the arcade or the mall. Even if you had nothing to buy and nothing to do, that’s where we’d all go to hang out. And before that, it was soda fountains and libraries and basically whatever public place you could just go and be with friends.

Jamie Kelly: Even in this generation, people still like to get up and go places. For me, growing up, that place was the arcade or the mall. Even if you had nothing to buy and nothing to do, that’s where we’d all go to hang out. And before that, it was soda fountains and libraries and basically whatever public place you could just go and be with friends.

So what we’ve created is this sort of trifecta of circumstances: We have a system that’s wireless and actually works; it’s rugged, it’s clean, everything. Inside of a location that is public that allows people to just go or watch or consume a brand new medium, which is virtual reality.

![]() Maeva Sponbergs: And it’s not until now that we’re getting on par with the technology and getting to where we need it to be. Because VR, as I’m sure you’re aware, is an old technology. And if this is the second generation of VR, or the second installment of trying to make this work—all of us within the industry—we still feel that there are so many things left to do.

Maeva Sponbergs: And it’s not until now that we’re getting on par with the technology and getting to where we need it to be. Because VR, as I’m sure you’re aware, is an old technology. And if this is the second generation of VR, or the second installment of trying to make this work—all of us within the industry—we still feel that there are so many things left to do.

Blake J. Harris is the best-selling author of Console Wars and will be co-directing the documentary based on his book, which is being produced by Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg and Scott Rudin. Currently, he is working on a new book about VR that will be published by HarperCollins in 2017. You can follow him on Twitter @blakejharrisNYC.

Feature Image Credit: Lindsay Jorgensen, lead artist – Fantastic Contraption