What Palm and Research in Motion are to smartphones, ODG and Vuzix may become to smartglasses — a cautionary tale of early innovation that failed to keep up with industry momentum.

In nascent markets where competition is under-developed, it’s easy to mistake modest sales growth for good strategy. Executives’ preference for encouraging short-term metrics obscures the evidence that long-term forces are moving against you.

For a prime example of an imminent disruption long in the making, let’s take a look at the current state of augmented reality glasses.

The main contenders were present last week at AR in Action in New York City. On display were the latest demos built for Microsoft’s HoloLens, ODG’s R8, some rare sightings of the Meta 2, and occasionally an errant appearance by Vive or Daydream. Even Magic Leap showed up to say much and show little.

Amidst this futurist playground, one contrarian notion was evident to shrewd observers — today’s AR is already very good. When discussing AR, most commentators opt to lower expectations by emphasizing the “early” nature of this technology. But there are a wide variety of compelling AR applications available today, and this “early” tech has found its way into schools, hospitals, factory floors, real estate agencies, marketing campaigns, and many other industries across the world.

So why is AR still a mere footnote to industry, an unknown concept in the collective minds of American businesses and consumers?

In a market ripe with opportunity, the standout is Osterhout Design Group. ODG has perhaps the best AR product on the market right now. The R7 glasses are lightweight, comfortable, and reasonably fashionable. The image quality is very good — its photorealistic holograms are convincing. More impressive are the coming-soon R8 and R9, which boast HD displays with wide fields of view. Lastly, the Android-based operating system is highly accessible from a UI/UX perspective.

ODG markets the devices for light enterprise use cases. They’ve announced a series of partnerships addressing logistics, maintenance, and health and safety functions for numerous industries including energy, heavy machinery, complex manufacturing, and medical devices.

All this early success is commendable and would be cause for unbridled optimism, except that Palm and RIM were in the same position for many years until the introduction of the iPhone.

Right strategy, wrong time

The smartglasses industry’s strategic miscue is that it remains wedded to conventional wisdom that is becoming less applicable by the day: With frontier tech, go enterprise first. Corporate customers are less price sensitive. Productivity is King, so aesthetic considerations don’t matter. Small volume production is more manageable and marketing less costly. Wait for the market to mature before you go consumer.

This is perfectly logical advice and nine out of ten experts would no doubt prescribe this strategy. But nine out of ten companies will not win their markets, especially if everyone follows the same game plan. If you want to beat your competitors, you must do something differently.

The enterprise-focused hardware strategy is ultimately wrong for AR glasses because this industry will not be segmented by user types. What we mean is that the vast majority of use cases do not require specialized hardware. One form factor and one set of standards can serve the needs of professionals and casual users alike.

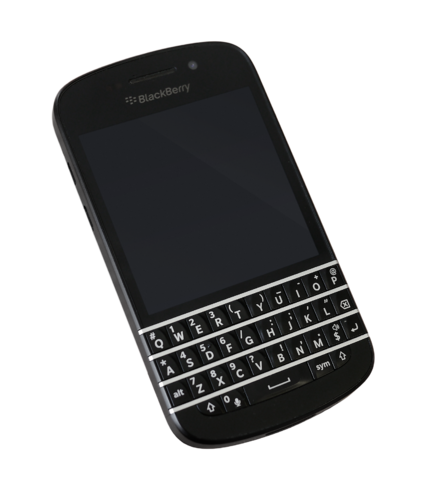

For perspective, consider the Blackberry. RIM stayed enterprise-focused for so long, they were completely upended when Apple decided to stop segmenting the market and just build a better phone for everyone. At first, many observers thought that RIM could hang on by staying the course — remain focused on enterprise/government customers with appealing features like strong encryption and the Blackberry email client. But soon Apple would catch up on security, and it turned out that many of the “consumer” features appealed to executives, too. It wasn’t long before corporate IT departments began supporting iPhones, and RIM never recovered.

The iPhone revolution of 2007 showed us that enterprise/consumer was not an appropriate market segmentation for phones. A decade later, the coming smartglasses battle is no different. ODG, Vuzix, Epson and others are busy marketing enterprise glasses for $799–$3,000 per pair (!), while Snap hawks a much cheaper product with very low utility, yet is stylish and well received. Is this not a market ripe for disruption?

Casting a long shadow

Announced last week at WWDC, Apple’s ARKit is the clearest expression yet of Tim Cook’s intention to make Apple a force in AR. Speculation is rife that AR will be a core feature of the tenth anniversary iPhone coming this fall. Some observers maintain that a snazzy pair of glasses will debut simultaneously.

Apple is not often a first-mover in technology — but neither does it hurry to catch up to others. Apple’s core strength resides in applying brilliant design to transform the user experience, and it waits until technology matures to a point where these skills become relevant.

Has AR reached that tipping point? At AR in Action (and so many other conferences this year), we clearly felt so. From holograms to positional tracking to environment mapping and computer vision, so many of the right factors are in place. A tremendous prize is ripe for the picking, but no one has maneuvered aggressively to claim it.

Surviving an asteroid

Whether or not they arrive in time for iPhone X, all AR companies must expect that Apple’s smartglasses are only a matter of time. And that is an eventuality that should be confronted now, because later will not be an option. Apple has so many advantages it feels impolite to recount them: complementary devices, brand recognition, strong customer relationships, exceptional designers, an unmatched supply chain, and $250B in cash…how does one compete?

Here is a radical idea: partner with Nintendo. Nintendo is a brilliantly creative company with a strong brand and very loyal customer base. And Nintendo is not afraid to experiment with new game play methods: the original Wii sold over 100 million units (far outpacing Xbox360 and PlayStation 3) by reinventing how gamers interact with digital worlds.

Nintendo is fresh off the launch of the wildly popular Switch, which doubled-down on mobile and multiplayer gaming at the exact time that others were reinvesting in heavy consoles for stationary use, even in isolating environments (PSVR). The console qualities in which Nintendo excels – wireless tracked controllers, scalable graphics, 3D interaction and mobility – are ideal attributes for an AR gaming platform.

A year has passed since the Great Pokémon Craze of 2016 demonstrated the massive consumer potential for augmented reality. Why should such tantalizing experiences remain confined to 5-inch displays? Mobile phones – constrained to touch interfaces on tiny screens – cannot deliver the rich variety of mobile gaming experiences that consumers clearly want (as evidenced by the success of Switch). A full-scale glasses-based console that brought mythical creatures to life in our living rooms would be an instant cultural phenomenon — and would sell out all preorders.

Nintendo is the partner that could enable enterprise-focused AR startups to survive in the consumer world of Apple and company. After all, a partnership between a smartphone company and a gaming company gave us the world’s best VR headset, the Vive. Why shouldn’t a partnership between a smartglasses company and a gaming company give us the first breakout AR device?

Final thoughts

Today’s smartglasses companies appear content to accept big bites from a small pie. They do not recognize that a force is coming that will redraw the boundaries of competition in their market. Enterprise-centric features did not save Palm and RIM when a substantially better product redefined the phone industry, and smartglasses will be no different.

As it did with phones, do we need Apple to rescue us from mediocre AR? Perhaps Apple’s entry is the catalyst needed to make AR go mainstream — but history will show that the ingredients for success were available years before Apple arrived on scene.

Ramses Alcaide contributed to this post.