“Social VR” is rapidly building buzzword momentum in our industry, fueled by the many multi-user VR platforms recently launched or soon to go into open beta. To name just a few, there’s Valve’s Destinations, AltSpaceVR, Sansar from Second Life creator Linden Lab, and High Fidelity from Second Life founder Philip Rosedale. Hovering above them all, of course, is Facebook’s own upcoming social VR platform.

All of them, however, labor under a couple mistaken assumptions which are likely to limit their appeal. We saw similar mistakes occur a decade ago, when Second Life and other virtual worlds were all the rage in Silicon Valley and the mainstream media, but quickly lost their appeal when users failed to show up. This time, however, it’s not too late for us to make some quick course corrections.

High Excitement, Few Users

Implicit in most social VR platforms is the assumption that a mass market for virtual reality headsets is coming soon. As regular UploadVR readers know, however, expectations have fallen far short: According to SuperData, sales of high-end VR devices were slow in 2016, with Oculus and Vive selling less than 700,000 total. Oculus recently stopped doing demos in many department stores for lack of interest. And while the mid-range Samsung Gear VR leads the pack with nearly 5 million units, that’s still a fraction of the 100 million or so Samsung smartphones the headset was designed to work with. All this strongly suggests a lack of viral growth or a killer app to drive it.

It’s still possible we’ll reach a tipping point after the price point is small enough and the content catalog is large enough. But even then, what are chances we’ll see anything like a shared metaverse with a billion users in our lifetime? In the short to medium term, at least, we’re more likely to see social VR embraced by a small contingent of core users, leaving the rest of us behind.

This takes me to a related and even more difficult problem for social VR:

Real-Time VR in a Time-Shifting, Cross-Platform Ecosystem

Social VR arrives in the market at a time when broadband and mobile devices have totally remade our model of media consumption. Where it was once appointment-based, in which families and friends would regularly meet in person whenever their favorite TV show was on, we largely use DVRs and streaming services to time shift. Where content consumption was once built around passive, location-dependent contexts — think movie theaters, living room televisions — we now place-shift, carrying our content wherever our smartphones and tablets can accompany us. As this change took root, social media took the place of TV viewing parties. Instead of taking the time to watch our favorite show together with friends, we now share our viewing experience on Twitter, Facebook, and Snapchat.

Combine these two trends — slow growth of VR, plus time/place-shifting of content consumption — and you can see that social VR as it is typically conceived confronts a near-insurmountable adoption hurdle. Facebook and other VR developers are asking consumers to invest a fair amount of money and quite a lot of time on a platform most of their friends still don’t use (since most of them don’t even own a virtual reality device) which also runs counter to every content consumption convenience they’ve enjoyed for the last 7-10 years.

This will be a key challenge for VR apps like the one for Hulu, which enables multiple VR owners to watch the same video programming together as avatars sitting in the same virtual space. This is an impressive product, to be sure, and likely to gain an audience of fellow virtual reality enthusiasts — while the vast majority of consumers will be left behind. By and large, most social VR apps are created by the VR user, for the VR user.

I don’t mean to suggest that social VR is doomed, however — just that developers should reimagine what it means to be both social and VR at the same time.

Social VR Must Be Truly Social

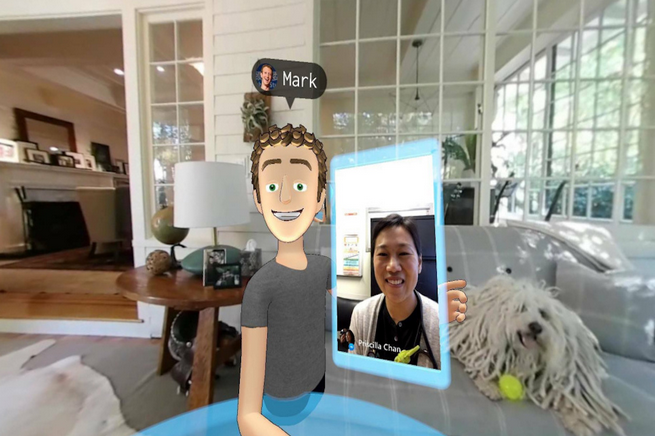

I believe the way forward is thinking about social VR embedded in a larger social experience that transcends VR. Or to put it another way: Once one of your friends puts on a VR headset, what do the rest of you do? We’ve all seen YouTube videos of people at parties laughing their heads off while one friend in VR flails around, trying to hit unseen zombies. Enjoyable to be sure, but the novelty of one person in VR while everyone else watches soon wears off. This highlights the greater challenge: Creating social experiences for virtual reality when the vast majority of consumers still devote most of their online screentime to the devices in their hands or on their lap — not strapped to their face.

Some enthusiasts have predicted that VR will soon be embraced by consumers with as much fervor as smartphones. This may one day be true, but the analogy misses an important distinction: Smartphones were and are still phones, capable of connecting with feature phones of a previous era, and the landline phones of an even earlier era. Smartphones have succeeded because for all their powerful features, they also maintain a direct connection to the platforms which came before them. To have any chance at succeeding in a similar fashion, virtual reality developers must devote themselves not just to creating powerful 3D experiences, but also powerful bridges to decades of 2D content, the devices they were built for — and just as key, the people still connected to them.

This is a guest post on UploadVR not produced by the core editorial team. Balaji Krishnan is founder and CEO of DabKick, a live media sharing service, and Snapstick, a mobile-to-TV streaming technology acquired by Rovi.