It’s been 20 months since I tried the Varjo prototype and its promise of VR at extreme resolutions. Now in 2019, the company has made it a reality.

Dubbed the Varjo VR-1, this enterprise headset has launched today to 34 countries, including the U.S. It costs $5,995 for the unit, though a $995 per year license for software and warranty is mandatory in the first year. That also comes with 24-hour support. Clearly, the VR-1 is targeted for commercial use.

But does the VR-1 provide an image quality that has been missing in consumer VR headsets? It actually does.

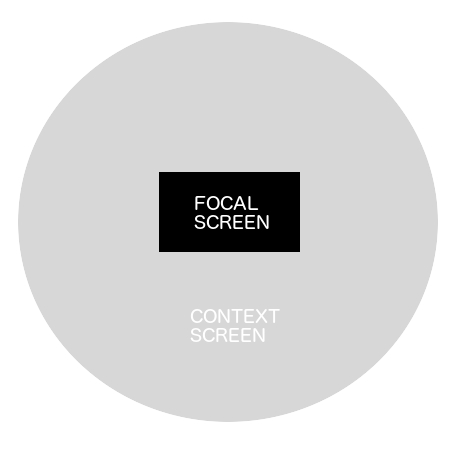

The main screen of the unit, what Varjo calls the “Context screen,” is the same resolution as the Vive Pro and the upcoming Oculus Quest, 1440×1600 per eye. Overlaid the very center of the main screen is a micro display that is 20X the resolution, 3,000 Pixels Per Inch or 60 Pixels Per Degree. The view in that window, the “Focus Screen,” is astounding. The company calls this combination of screens the Bionic Display.

“If you can see a thing the same way as it would appear in real life, you can trust what you see,” said Urho Konttori, co-founder and Chief Product Officer of Varjo. “You can keep your design process virtual. It must reach that pivotal resolution, where you can start doing things differently.”

Once again for my Varjo demo, I’m standing in a living room. Built in Unity software, this is a more modern home than the one I saw in June 2017. Lines are finely detailed. The textures around me in that living room feel more real. At what Varjo calls “Human-Eye Resolutions” the carpet looks like carpet, a vase looks like porcelain, and a map on a wall is an actual map you can use.

(The headset also works with Unreal and AutoCAD, besides Unity.)

Another demo, a flight simulator, had a detailed cockpit with displays with usable information. They looked like real computer monitors. Such resolution will mean everything for the viability of virtual desktops where a user has a dozen virtual monitors floating around them.

The Context Screen is an AMOLED that runs at 90hz, the Focus Screen is a 60hz OLED, though I couldn’t really tell the difference in frame rates. The real estate of the Focus is larger compared to the 20/20 prototype of 2017. Horizontally, it is a third of the width, and vertically, a fifth of the height. The transition between the two screens is also much improved, with the image being nearly seamless in alignment and color. Here is a graphical representation of the VR-1 similar to the one I made in 2017.

Of note in the image is the shape of the Context Screen, which is quite circular and only has an FoV of 87 degrees, due to a 3.5-inch screen. It felt somewhat limiting, but then that also keeps the eyes focused in the center, at the .7-inch Focus Screen. As a byproduct of a smaller screen and FoV, the PPD of the Context Screen is greater than the Vive Pro, 16 PPD vs. 14 PPD, since they have the same resolution.

The headset features carefully tooled lenses that are larger than Rift’s and are not Fresnel. With its size, the sweet-spot for the VR image was very large. Furthermore, with high-refractive coatings on the polymer lenses, there was no detectable reflections, color aberrations, god-rays, and the like. It makes the image you experience that much more visceral. The company spends 20 minutes adjusting each unit, calibrating it perfectly using hundreds of megabytes of data to further lessen optical distortion and color aberration.

Of course, all the detail you experience from the Focus Screen comes at a cost. The demos I participated in were ran on an RTX 2080TI and I could tell the framerate was still suffering at certain times, such as in the one used for designing cars. But the car looked nearly photo-real. Fine textures that created Moire patterns on the screen edges, looked sharp and perfect in the center. Of course, Enterprise customers would have workstations with more power, or even render farms that wouldn’t have this frame rate issue.

“For car designers, this is now actually the real deal,” said Konttori. “They can move much of their design process to stay purely virtual instead of having to do physical mockups. Because now everything can be replicated so incredibly well inside VR. You see exactly what you would see in the real world.”

Other demos ran smoothly. Two locations built with photogrammetry ran perfectly smooth. And with the extreme resolutions, they truly looked photo real. An artist’s studio captured in just two hours felt really there. I could see the pressure marks in clay sculptures, notice damage and dirt on tables. Objects were perfectly represented.

Another demo had a letter chart from an Optometrist at a distance. The Focus screen allowed me to read every line of the chart except for the bottom one with the tiniest letters, where as through the Context Screen the text was just fuzzy pixels after only 3 of the 10 lines.

The headset also features proprietary eye-tracking software, though it is currently only being used for software interactivity, and not the long-sought-after foveated-rendering. The demo for the eye-tracking, where you stand inside an airport control tower, was effective. A circular reticle moved around the screen, fluidly matching my sight. I could just look at planes to see their trajectory, or examine monitors to have the data presented there expanded.

“This is the most accurate eye tracker in the world,” said Konttori. “It is accurate to a sub-degree. One degree is roughly the size of your index finger’s nail at arm’s length. We are able to be more accurate than the size of that.”

Though, the eye tracking was very accurate, it did have its flaws. The tracking software had issues with my eyeglasses, so I had to use it without them—people will have to invest in contacts until the company finishes tweaking the software.

Another benefit of the VR-1 tracking both eyes is automatic IPD adjustment, similar to VRgineers XTAL headset. Your pupils are detected and a motor adjusts the lenses. No further physical calibration was necessary, with the visual converging correctly and seemingly reducing the eye fatigue I usually feel after a long VR session.

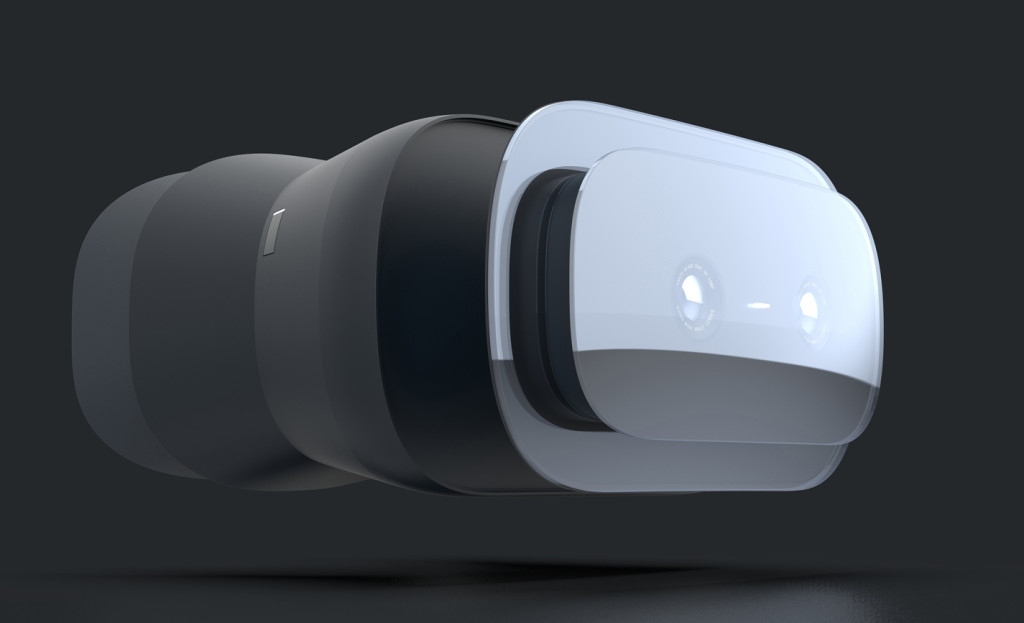

As for other aspects of the VR-1, the ergonomics are good. Though it is a bit heavy — 905g or almost double the Rift’s 470g — it didn’t bother my head or neck during the brief demo time. With a pivoting head strap, a top strap to tighten in a way similar to the Rift, and a dial at the back of the head to tighten it there, my desired level of comfort was easily obtained once the dial made the headset strap firm. The back of the head strap also has the largest cushion that cups the back of the head that I have seen on a VR headset, which helped greatly.

The space inside the headset was ample, with room for my glasses to sit there and not get pressed against my face. The active airflow worked, so that even after 45 minutes of use, my face was not hot and there wasn’t even a hint of fogging up. The widening front of the headset is quite large, but the mirror finish on the faceplate gives it a unique look.

There is no built in audio, leaving it to users to provide as cheap or expensive headphones as they desire. With a 10-meter wire tethering you to a PC, there is more than enough slack to move around the room. It uses SteamVR and its 2.0 tracking, so you can move around all you want. There are two buttons on the top of the unit, a Menu button and an Action button, so some software will be usable without the Vive Wands or other hand-tracking controllers for Steam.

As said before, Varjo’s core audience is enterprise users. That means architecture modeling, virtual designs, simulations for worker training, and more. Partners already announced include car manufacturers Audi, Saab, Volvo, and Volkswagen, airplane manufacturer Airbus, construction company Sellen, architecture firm Foster & Partners, and military simulation-developer Bohemia Interactive. Some of the high-end simulations that large corporations or the military use can cost millions of dollars; Varjo is clearly looking to tap into that training market with a product that is a fraction of the cost.

“Extending this to training, eye tracking is a really interesting tool because the trainer can see what the trainees are looking at,” said Konttori. “You can now see interesting analytics on the performance of the trainees. Surgeon eye tracking data, for instance.”

A prosumer with deep pockets could purchase it from varjo.com, but they would have to also have a Business ID and know that SteamVR content is not completely compatible, yet. Everyone who orders will immediately get a shipping date. And the company said they are shipping in enough quantities that even if demand is high, customers will have to wait weeks, not months for delivery.

Credit: VentureBeat" width="1024" height="623" oldsrcset="/content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 1024w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 300w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 768w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 16w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 32w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 28w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 56w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 64w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 1000w" oldsizes="(max-width: 1024px) 100vw, 1024px" />

Credit: VentureBeat" width="1024" height="623" oldsrcset="/content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 1024w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 300w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 768w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 16w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 32w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 28w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 56w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 64w, /content/images/2019/02/varjo-mixed-reality-mockup.jpg 1000w" oldsizes="(max-width: 1024px) 100vw, 1024px" />The future of the VR-1 itself could be eventful. Varjo will be announcing details this summer about a Mixed-Reality add-on. Users will be able to remove the shiny faceplate of the headset, and attach a new front which will have cameras. Thus, Pass-through Augmented Reality will be possible on the VR-1. The company even left room at the front of the headset to fit the additional chips and hardware needed. These further capabilities may prove irresistible for companies looking for high-end MR hardware.

So why should VR consumers care about Varjo VR-1? What about VR gamers who aren’t going to have access to projects that would need a $5,995 headset?

The VR-1 is a glimpse at what is coming down the pipeline in a few generations. Obviously, eye-tracking is coming with Vive Pro Eye, but the graphical promise of foveated rendering likely remains a few years away.

And what about resolution? To get the detail of the Focus Screen on an entire screen, would require a headset with 2.5x pixels of an 8K screen. So that is generations away for consumer tech, both for the screen technology to be affordable and for GPUs to catch up—though the aforementioned foveate-rendering will help.

Two years of frequent prototyping and beta-testing has led them to the finish line of development with all the feedback they have received from early users leading to the launch of this high-end headset for the professional set who need the extreme level of detail.

“One architect said to us, ‘If you can’t see the details, you can’t see the big picture,’” Konttori said.

By the time this story is live, the official Varjo website should have more details.

Editor’s Note: We’ve corrected small typos and updated the video at the top of this article.