I always thought I’d be more prepared for “the talk” than my parents were. It would be a priority of mine to have historic references on hand, pull from life experiences, maybe even pick out an educational video from the library – you know, make things easier on myself. I made sure to learn as much as I could about this topic so that, by the time it was my turn to have that serious sit down with my kids, I would be ready for their questions. Being a writer, at the very least, I figured I’d be more able to articulate what to expect when it happens to them. What I’ve discovered though, after actually becoming a parent, was that no amount of preparation will make this talk any less stressful.

I mean, just how do you tell a young child that some people might not like them because of the color of their skin?

What I do find solace in is the fact that I won’t have to first try to convince my daughters that racism exists; being our children, they’ll listen to what my wife and I have to say. I’d also foresee the girls being naturally empathetic to our shared experiences. This in turn takes some of the edge off as it promotes uninhibited dialogue. As a family, we’ll never yearn to discuss such things at the dinner table. But we’d at least be comfortable enough to openly deal with whatever comes our way. That truth is very important given the nature of this topic. Not everyone is going to be willing to listen to my children’s concerns like my wife and I will when life becomes more challenging for them.

As I continued to mull this over, I wondered how I could surround my children with people who’d be willing to listen to their concerns. As of right now, a decent amount of my white friends would rather shy away from the conversation. It’s just too uncomfortable a topic. Although to a lesser extent, some feel as though our struggles are fabricated. That we either unnecessarily lump race into every dispute or that most of our difficulties in life, regardless of how we’re treated, are solely attributed to our own actions. They’re basically closed off to what a lot of people like me face on a daily basis. Still, I wondered what could be done outside of being careful of who we trust.

As the virtual reality industry continues to evolve though, it can be used to help people see things from the perspective of a minority in America. You know, wear someone else’s shoes and all that. This sort of thing has helped people see past their own experiences in the past (it’s a popular idiom for a reason).

I found the work of Dr. Jeremy Bailenson, Ph.D., a Thomas More Storke Professor in the Department of Communication at Stanford University. Among his numerous accolades, which included being the founding director of Stanford’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab, his doctorate in cognitive psychology from Northwestern University piqued my interest.

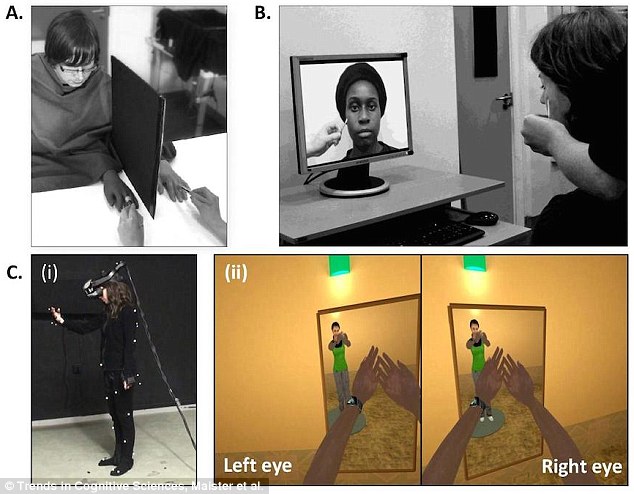

Dr. Bailenson’s main area of research deals with digital human representation, especially in the context of immersive virtual reality, as per his bio. For years, he’s researched how VR can help to facilitate change in a person’s perceptions of others. For instance, in an academic paper he co-published, “Walk a Mile in Digital Shoes”, Dr. Bailenson describes an intervention method developed by Galinsky, A.D. and G. B. Moskowitz called Perspective Taking. It deals with how people see themselves vs. others during social interactions – when judging ourselves, we tend to rely on outside forces to justify our actions. That’s not the case when judging others. That said, extensive research has shown that when we’re asked to take on the perspective of the person we’re judging, in a virtual setting, we tend to give them the same benefit of doubt we’d give ourselves.

Then there’s also Courtney D. Cogburn, Ph.D., an Assistant Professor at Columbia University’s School of Social Work. Dr. Cogburn has partnered with Dr. Bailenson on a project called “Examining Racism with VR”. The idea was to use an immersive VR experience that allows participants to embody a person of color (seemingly, more Perspective Taking).

Dr. Cogburn explained how she was building on research that challenged the way people talked about or measured racism. “We tend to talk about racism as things we do to each other on the basis of race,” Dr. Cogburn explained. “You know, being called a name, someone being followed in a store, or being directly harassed by a police officer. [Dr. Bailenson and I] are trying to build on work that indicates that racism is actually much more complex and nuanced than those types of experiences…[Like] being praised for being articulate or someone being surprised that you didn’t come from a single parent home or whatever stereotypes that might sneak their way into discourse in interactions.”

Dr. Cogburn and Bailenson were also interested in how they could expose people to understanding the structural nature of racism. “[It’s important to] understand the patterns of discrimination, policy and legislation that systematically disadvantages groups of people…if we hope to do anything about the effects that racism has on people’s lives,” Dr. Cogburn said. Unfortunately, something like that seems borderline impossible. It can be difficult to get people to listen when dealing with a single incident, let alone something more systemic.

She then detailed how they would be using qualitative data to help design content for the project. Everything is rooted and documented in reality, being careful not to take artistic license while constructing these scenarios. This is to help combat some of the resistance people will have towards the experiment; discounting its relevance as the scenarios “could never happen” in real life.

“Our team is comprised of about a dozen scholars, a majority of whom face issues of racial bias every day,” Dr. Bailenson explained. “Part of the reason the design process is taking months is that we continually discuss the experiences of the team members, and spend time deliberating which types of experiences will actually be uniquely suited to VR.”

Though their project is still in the design phase, using virtual reality as a means of evoking empathy is supported by sound research. Dr. Bailenson has worked multiple VR experiments dealing with a person’s negative stereotypes. None of his studies found “the answer” to today’s ills, given their complexity. Still, he was able to encourage a decrease in prejudiced thinking using different virtual programs. I particularly made note of the body transfer effect – where a person’s brain helps them to believe they are the person seen in a mirror through their headset – created through diversity training software called the Minority Mirror. Used for businesses looking to improve social awareness, the software places people in the bodies of different minorities and in some cases, genders. All of a sudden, a white female is transformed into a black male. Once that happens, another avatar comes up to the person and starts saying negative things about the participant’s race (that of which he or she sees in the mirror).

Interestingly, years of research revealed that the persons wearing the headset showed more empathy after coming in contact with the hateful avatar. When I asked if these feelings of empathy were short lived, Dr. Bailenson pointed out how his lab had “completed collecting data from an immersive empathy study that examines the effect of the treatment directly after the experience, two weeks out, four weeks out…we plan on analyzing the date in the next few months to examine how immersive VR compares to traditional role playing over time.” In other words, the impact of the study doesn’t end when the headset is removed.

The information I got from Dr. Bailenson and Dr. Cogburn was invaluable, in a sense that it gave me hope. Maybe people can have a change of heart and become more open to hearing what minorities have to say about racism. As uncomfortable as it may be, there’s a real need for honest conversation among peers. I’m sure that their Examining Racism project, based on the progress made from similar software, will help to facilitate these difficult discussions given time.

While this is all true, I do fear that there are some unique challenges hindering the effectiveness of this sort of approach. Some of which, I noticed after talking with Nonny de la Peña.

Nonny de la Peña is an award winning journalist, having written for reputable news organizations like Newsweek and The New York Times, and has helped pioneer VR empathy projects. It could even be argued that she is more readily known for her work in immersive journalism, a genre she is credited in creating. As CEO of Emblematic Group – a digital reality media company that produces immersive VR content – she recreates events that people can experience in virtual reality. One of her major pieces, Project Syria, was the topic of our discussion. Not because of how powerful it was for those who experienced it in her studio, but because of the blow back she got after releasing it on Steam.

“We put Project Syria on Steam and the response was horrible,” de la Peña exclaimed. “Racist, vitriolic responses. I would expect that our game [wouldn’t be liked] as a game. We’ve [only] put up $35,000 to make it. So I would understand that kind of criticism. But no, it’s all racist.”

While she spoke, I headed over to Steam to check out the comments for myself. If you take away the comments about Project Syria not being an actual game, a valid point for another discussion and perhaps more a result of Steam’s user base consisting of almost entirely gamers, and people complaining about the visuals, a lot of what’s left isn’t appealing. With people claiming it to be “ISIS propaganda” and others asking “how to sink refugee boats”, it’s honestly disheartening.

For those that don’t know, Project Syria (PS) is a piece that provides an immersive look at the effects of the Syrian civil war on the country’s children using virtual reality. This is done by recreating a tragic event on the streets of Aleppo – a bomb goes off in refugee camp, wounding and killing many people living there – using found footage, photographs, and tons of documentation. Outside of improving the graphic fidelity of the piece (this was produced back in 2013), PS is probably the best chance anyone has of “experiencing” this sort of event other than actually visiting the country.

De la Peña didn’t expect to receive so much push back from the Steam community. It’s understandable really. Those of us who frequent the platform are more accustomed to the toxic behavior that the community can produce. I’d imagine it was even more shocking considering the opposite happened whenever she premiered her piece at conferences. For the most part, people seemed genuinely moved by what they saw. Some were brought to tears. Others came away asking how they could help in the relief efforts. I asked her if the experience was somehow more believable at these conferences. That maybe the gamers on Steam felt that she was exaggerating to push some sort of agenda.

“I could show you some of the art bible [from Project Syria] which shows how very carefully our reconstructed streets were created,” De la Peña explained. “And I had people from Aleppo come in through it and just bawl because we even got the color of the bricks right – because they were a very special color from Aleppo. So it’s always easy for me to counter those accusations with the unbelievable in-depth documentation that we do. And that documentation and the ability to find those pieces and what’s true is based on my many years of being a careful, considerate, thoughtful, and to the best of my ability, a truthful journalist.”

The truth of the matter is, there are always going to be those persons who are reluctant to hearing or even acknowledging a person of color’s side of the story. Some people don’t want to deal with anything that might disrupt their view on what life is like here in the United States (or any part of the world really).

“I think timing is always a factor,” Dr. Cogburn remarks. “Socially and culturally we’re in this unique space where a lot of people are alert and awake and paying attention, especially white people who might not have otherwise been paying attention…there are people who believe in the idea of justice and fairness but they don’t understand racism. We’re in a window of time where there’s a lot of people [who] are very aware that something is going on with race, even if they don’t fully understand what it is and what is happening, specifically linked to police violence because of all of the media coverage that have people more aware and willing to talk and listen.”

It’s important to be able to share in the troubles of our fellow man. Shining a virtual light on certain issues can both educate people, potentially bringing about change, as well as more immediately provide vocal aid to those of us who may be suffering. During my interview with De la Peña, she informed me of a story she did about a Muslim family that was unfairly targeted by the FBI after 9-11. Because she needed a shot of their Mosque to go along with the piece, she contacted a representative to come and view the rough cut of the video.

“He came in, and he watched the piece and he started crying,” De la Peña said. “He kept saying, ‘Why would you do this? Why would [someone like me] be willing to help?’ I didn’t know how to answer that question.”

He wasn’t sad, but was instead overcome with emotion. Someone who didn’t look like him, who wasn’t Muslim, and who hadn’t been negatively affected by the treatment of his people, was willing to help tell this story. It was a powerful moment for both of them, but even more so for the representative of the Mosque. The world is changing. Despite the current political climate, things are slowly progressing. People are starting to listen.

I personally hope, for my children’s sake, that eventually they’ll do more than just listen.