I’m secretly terrified about VR’s future. Not because of the economic risks or technical challenges, but because of its perception and the massive, hulking elephant in the room that is the blame game.

I’ve been working in videogames in one way or another for about 10 years now and something I’ve seen rear its ugly head time and again is outcry over violence and adult content. It happened when Modern Warfare 2’s ‘No Russian’ level let you open fire on an airport filled with innocent people, people flared up over Mass Effect‘s sex scenes, and Grand Theft Auto V caused a stir with its torture sequence. Game controversy and media blacklash has undeniably died down in the past few years, but I’m dreading its inevitable return once VR really starts to catch on.

Surprisingly, though, the people that are going to be rating these experiences don’t seem anywhere near as concerned.

A few weeks ago the Australian Classification Board (ACB) awarded its first VR rating. The organization gave PlayStation VR’s Batman: Arkham VR a mature ‘M’ classification, citing ‘VR interactivity’ as one of its main factors. Just last week, we also reported that the USA’s Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) had given PlayStation VR Worlds a similar ‘M’ rating, though without making any mention of VR’s unique aspects as a medium. When we followed up with the ratings body, they told us they believed their current system was suitable for VR games.

For reference, here is what the ESRB said:

At this point in time, we believe that the current ESRB rating process effectively assigns age and content rating information for VR games, taking into account the content of a game and the context in which it is presented, including player perspective.

ESRB ratings are designed to give parents the tools they need to help make informed decisions about which games are appropriate for their family. We’ll continue to monitor the evolution of VR games and will make modifications to the rating system if and when warranted.

Truth be told, I’m not entirely sure that existing ratings bodies are ready to deal with the influx of VR titles. I don’t think the ESRB’s response considers what will happen when VR has its ‘No Russian’ moment. What happens when a parent discovers that their child is realistically shooting and killing humans in VR? Or being ripped apart by some hideous monster that’s really breathing down their necks? I struggle to see a positive outcome.

So I took a trip to one of the most well-known and respected ratings bodies in the UK, the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) to talk about how they were preparing for VR’s arrival.

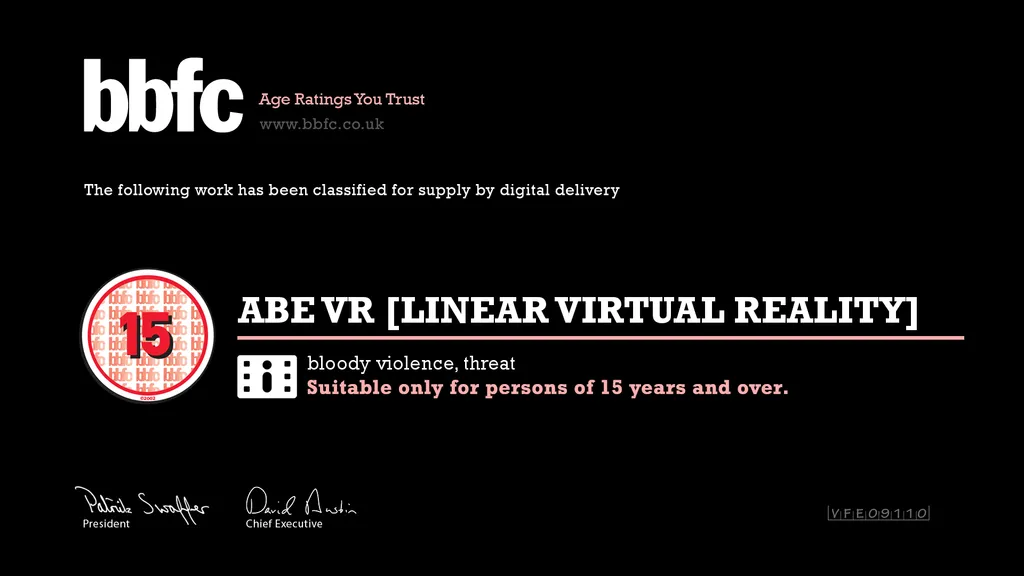

The BBFC has already rated one VR experience; Hammerhead’s ABE VR. In Chief Executive David Austin’s words the company has “just dipped our toe in the water” of VR, but it’s confident that it’s ready for the arrival of a new medium.

“We’re developing new services all the time in response to industry requirements and what the public want and expects,” Austin tells me. “But VR is the newest of all, so we’ve only so far classified one piece of content which was a short film called ABE, and we gave it a 15.”

15 is the third highest rating the BBFC gives, sitting behind 18s and R18s. According to the official guidelines, violence can be strong, but not dwell on the pain it inflicts, and disturbing actions should not be conveyed in ways that should be copied. Giving ABE VR that rating is one of the reasons I wanted to talk to the BBFC out of all the classification systems out there. When we saw this experience earlier in the year we became so immersed in its terrifying world that we forgot it wasn’t real and feared for our own safety. That’s something traditional 2D media has never really done. Surely that had to play an important part in giving the film this classification?

“We certainly took account of the immersive nature of VR,” Austin says of review process. “It’s the same way that when we’re classifying 3D; we take account of the stronger impact of jump moments…characters coming up from behind.” To Austin’s point, the BBFC does sometimes find that 3D and IMAX experiences are worthy of a stronger rating than the 2D experience, in which case it will give both the 3D and 2D versions that higher rating.

There’s a difference between taking VR “into account” and putting it at the center of your reviews process, though, and I’m not convinced the former is entirely effective. When I challenge Austin about the impacts of stronger, more realistic violence in VR and if the BBFC would consider imagery to go too far, he explains “it would absolutely depend on the content.”

“I don’t think it would depend on if it’s VR or not,” he said. “It would depend on the content. We rarely intervene with regular narrative films in terms of insisting that content is removed because it is illegal.”

I have to admit I’m a little surprised by Austin’s confidence in the BBFC’s current ratings system. So I ask: what if there was a VR experience in which you were realistically in control of explicit violence of a sexual nature or otherwise? Something that doesn’t hold back on its depiction and puts you in the driver’s seat.

“Yeah I think that it is potentially problematic,” he said. “We’d have to see the content but what you’re describing is potentially problematic.”

We’re probably not going to see that content any time soon. VR isn’t likely to challenge our morality too much while it’s still such a young medium, and maybe the BBFC and other ratings systems like the ESRB will be able to ease into the idea of altered ratings with the first wave of content.

Austin soon steers us toward perhaps the most important and relevant point: unregulated content. That’s what he points to when I ask him if he thinks VR will eventually stir up a moral panic.

“I think whenever we’ve had a moral panic it tends to be when something hasn’t been regulated,” he states, “So if you go back to the early 1980’s, well you could go back to the beginning of film, but let’s go back to the early 1980’s when video was unregulated. There was a panic then about lack of age ratings and children accessing the most challenging content, it was mainly horror content back then. And the response was to regulate.”

That may sound like an obvious conclusion but here’s the thing; both of the main VR headsets available now are full of unregulated content. The HTC Vive is driven by Steam and Steam doesn’t require developers to get an official age rating, though mature content will first ask players to verify their age before they can view a game’s store page. The same goes for the Oculus Rift via the Oculus Store, and Oculus also rigorously tests games for their comfort factor. Violent experiences like The Brookhaven Experiment and Edge of Nowhere are just sitting there without these official ratings.

That’s always been the case for Steam, though, and when panic does arise in the gaming industry, it’s usually due to what’s been caught on consoles, not PCs. As strange as it seems to say, Rift and Vive are likely guarded behind their relative obscurity right now, but this is an area both will definitely have to look into as it pursues the mainstream market.

Outside of this, however, Austin isn’t predicting that same media outcry that I’m so concerned about.

“I see no reason why there should be a moral panic,” he tells me on more than one occasion.

Given his measured responses throughout the interview, I can predict Austin’s response to my final question, but I ask it anyway: do you think VR will necessitate a new ratings body?

“I think another rating system could potentially cause confusion and I think we’re quite capable of rating VR as PEGI is capable of rating VR in games and I see no reason why there should be an exception or a new rating system,” he said.

I left my interview with Austin feeling somewhat conflicted. While I admired the BBFC’s confidence in its ratings, I still think VR is going to fight an uphill battle when it comes to media depictions and parental outrage. But maybe the message here is the same it’s always been: it’s up to parents to properly assess the type of content their children are experiencing, the BBFC is just there to guide them.

“As long as the industry behaves responsibly,” Austin says as we wrap up, “as long as they work alongside regulators that are trusted by the public, it should be okay.”

I guess I’ll just have to trust him on that one.