How do you think virtual reality will improve over the next few years? You’re probably hoping for better ways to see, hear and touch virtual worlds. Michael Abrash, chief scientist at Oculus, seems to agree: when he outlined his predictions for the next five years of VR last October, he focused on these three senses.

But one sense Abrash didn’t mention was smell. Using your nose in VR might sound slightly unnecessary, superfluous even – an optional extra once visuals, audio and haptics have been perfected.

Yet smell is central to how we perceive and remember the world, and without it VR will arguably always be a bloodless imitation of reality. Anosmics, as those without a sense of smell are called, have been found to suffer from a reduced quality of life and even severe depression. Describing the misery of losing her sense of smell, the documentary maker Elizabeth Zierah explained how she felt “dissociated” from the world around her. “It was as though I were watching a movie of my own life,” she wrote, and found anosmia far more traumatic than the effects of a stroke that had left her with a limp.

Smell is also the only sense directly linked to the amygdala, part of the brain closely involved in our feelings, meaning that scents can be particularly evocative of powerful emotional memories. Many of us have had the sensation of catching a whiff of something that takes us back to a particular time, place, and emotional state – something impossible in current VR.

Benson Munyan III, who researches smell and VR at the University of Central Florida, recalls driving out to his grandma’s house as a child. “And as soon as we arrived we would see rose hedges that were on her driveway. So getting out the car the first thing we would smell was rose. That has stuck with me until today.”

Munyan is one of a handful of scientists finding out how we can smell our way around VR. Having served with the US military in Iraq, Kenya and Djibouti, one of his key research interests is getting former soldiers to don VR headsets so they can face up to, and overcome, their traumatic memories. Smell has been used in VR PTSD treatment previously, he explains, but until now the difference it makes to immersion has not been quantified.

Figuring Out How Smell Affects Presence

Along with colleagues, he created a VR experience where you have to search a creepy abandoned carnival at night for your keys. In the same room, they set up a Scent Palette, a $4,000, shoebox-sized silver box that fires out certain smells at the right moment during the experience – so smoke when a ride crashes and bursts into flame; garbage from an overturned bin; and the more pleasant odors of cotton candy and popcorn.

They found that piping in smells gave participants a greater sense of presence as they made their way around the spooky carnival, while removing odors caused their sense of being there to plummet.

But there is a problem: pump too many different smells into a room for too long, and you end up with a very weird mixture of pongs. After lengthy sessions, “that room can smell of smoke, or garbage, or diesel fuel or whatever the combination is,” Munyan says.

Not only might this confuse your nose, but a consumer version would mightily annoy anyone who wants to use the living room after you without it smelling of candyfloss and garbage. Odors also need to be synchronized with your VR experience, but it takes time for a smell to reach you from a box in the corner of the room. By the time you smell smoke, you may have already moved away from a fire in the virtual world.

Some companies are already working on these problems. Olorama, a Valencia-based company, produces kits (cost: $1,500) that they say quickly deliver up to ten smells toward headset-wearing users. Their scents include ‘pastry shop’, mojito, anchovies and ‘wet ground’ (gunpowder, blood and burning rubber are ‘coming soon’). They say that their aromas are based on ‘natural extracts’, suggesting they dissipate more rapidly that standard chemical-based scents.

Problems Adding Smells To VR

Another solution might be to have a smell machine incorporated into a VR a headset, meaning odors reach your nose almost immediately and don’t stink out the entire room. Such an idea has already been prototyped: the FeelReal mask, launched on Kickstarter in 2015, promised not only to release smells but also vibrate and blast your face with hot or cold air and mist.

The mask was not a success, however, and joined an already long list of failed products like Smell-o-Vision and the iSmell. The Verge described wearing a FeelReal mask as like “putting an air freshener in a new car on a hot day. Then imagine burying your face in one of the car’s plastic seats. Then imagine the car’s driver is navigating some tight curves very quickly”. It failed to raise even half of its $50,000 Kickstarter target.

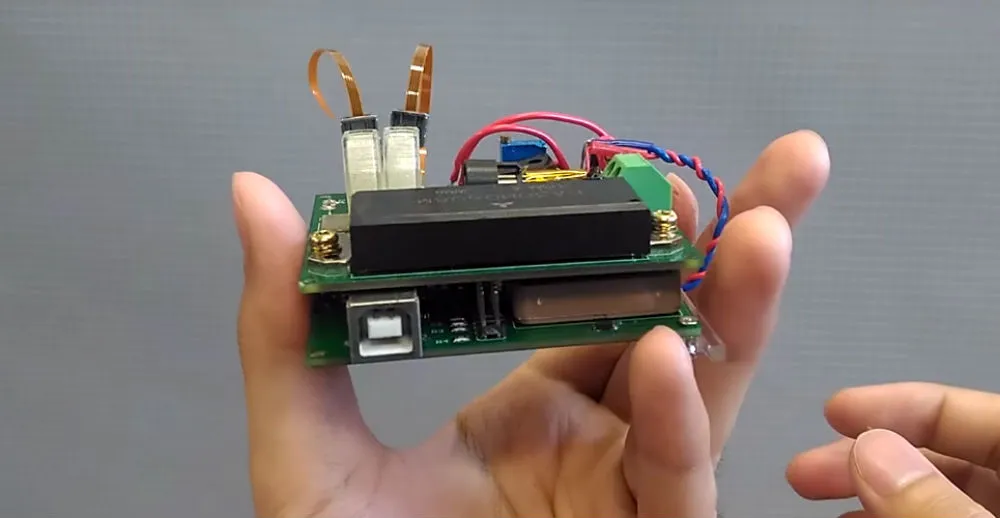

But other contraptions are in the works. A Japanese lab last year came up with a prototype smell machine small enough to hook over an Oculus Rift and sit just below the nose (see video), leaving the lower half of your face uncovered. Rather than using a fan, it atomises smelly liquids by blasting them with acoustic waves so that they waft upward into your nostrils. The lab says that because this does away with tubes, the machine doesn’t continue to smell when it’s not supposed to – one of the problems that has plagued previous devices.

One crucial feature of this device is that it can vaporize several liquids at the same time, in different concentrations, and so could potentially combine different smells to make others. The holy grail of VR smell research is a basic ‘palette’ of smell components that could be mixed to make thousands of other odors, rather like a headset screen can create any color from a few basic ones. But this will be a considerable scientific challenge.

Consciousness-altering Scents

Takamichi Nakamoto, head of the lab at the Tokyo Institute of Technology which created the device, says a “huge amount of data are required to establish odor components [of different smells]. We can collect them to some degree but it is not so easy.”

“Consciousness-altering smells, for example the smell of fear present in the sweat of someone very afraid or scared, are complex mixtures and no-one knows the composition and they will not be synthetically recreated in a hurry,” says Tim Jacob, a smell expert at Cardiff University. “Smell is not like vision where from a primary color palette you can mix all colors.”

So there are a list of daunting technological challenges to solve before we can incorporate smell fully into VR. But the psychological hurdles may be even higher, because of the idiosyncratic way we all experience smell.

This is well illustrated by another experiment, published last October, where participants were told to hunt for a murderer’s knife in a VR house. Those who were exposed to the unpleasant smell of urine as they entered the virtual kitchen rated the experience as more presence-inducing – providing further evidence that smell helps us feel VR is more believable.

But participants often misidentified the urine smell as something else entirely. Some thought it was fish, others garbage, the bad breath of the killer, or the body of the victim, explains Oliver Baus, a researcher at the University of Quebec. Some even thought it was a pleasant smell because it evoked happy memories.

“We had one participant who said when they were young, they drove to school past a farm, and that’s what it smelled like,” he says.

In other words, our reaction to a particular smell is highly dependent on the context, or our previous experiences. “Although some cultural consistency in response to certain odors can be assumed to some degree, because the associations we each have acquired to odors is idiosyncratic, it cannot be assumed on the individual level and therefore cannot be used in a predictive fashion,” says Rachel Herz, adjunct professor at Brown University and author of The Scent of Desire, which explores smell.

If VR developers want to ever include smell in a game, says Baus, they are therefore going to have to give a lot of visual cues to tell players exactly what they are smelling. “The visual is dominant,” he says.

For now, smell in VR is seen as something of a bizarre joke, like the moldy timber and blood scented candle you can light while playing Resident Evil 7. But without using this overlooked sense, VR may never be able to pack the emotional, visceral punch of our real lives. For that reason, incorporating smell may become one of the biggest tasks facing the industry over the coming decades.