Jules Urbach is on the brink.

Rest is rare for the 43-year-old with curly black hair and just a touch of gray in his beard. The long hours put dark circles around his eyes. He often works through the night. He replies quickly when asked how much he slept the night before our interview.

“100 minutes,” he said.

The answer seems rather specific. Alissa Grainger, Urbach’s business partner, motions to his watch.

“He records it,” she said.

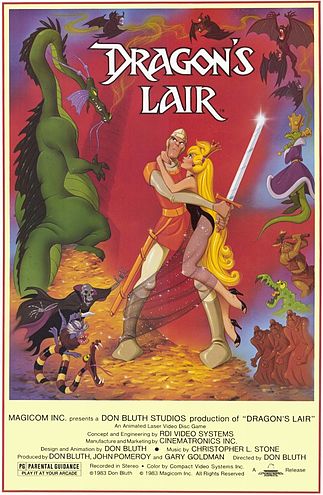

Urbach’s words come tumbling out faster than anyone can keep up. There’s an intensity to him. He’s obsessed with something and the circles around his eyes are a byproduct. There’s a future he’s been working toward for most of his life and he’s on a mission to deliver it as the co-founder and CEO of OTOY, a cloud-based 3D graphics rendering company. He’s a “mad scientist” as one investor describes him, with a Dragon’s Lair arcade cabinet at the entrance to OTOY’s office. The game from 1983 represented a breakthrough in graphics featuring advanced animation way beyond what was possible in traditional games at the time.  The game inspired Urbach to try and recreate it.

The game inspired Urbach to try and recreate it.

“I asked my mom to buy me the arcade game; she said no,” Urbach said. “So I actually recreated the game on my Mac IIfx first for myself, then to let people play it in the school lunch areas. I got into Harvard and Yale after sending them the source code to the game (they were skeptical I did it, never having seen digital video on a computer – this was before quicktime and DCT codecs came out). The deep eureka moment I had first seeing Dragon’s Lair as a kid was how beautiful and cinematic the game looked – maybe 30 plus years ahead of its time – yet how simple the concept was that made it work as [a] video game.”

Today, in a Los Angeles high-rise, the cabinet greets visitors to the office as a symbol of his life-long quest to enable anyone to make their thoughts a reality. If that sounds both inspirational and pretty far out, you understand what it’s like to talk to Urbach.

Life-Long Obsession

Back in 2004, a New York Times article described Urbach as a “caffeinated” man just like the one I met recently. At the time he was working from his mother’s house and thinking about how to piggyback interactivity onto an AOL chat window. What’s changed between then and now for Urbach is he gained a business-focused co-founder in Grainger. For the last 10 years his tireless engineering of a technology pipeline built for the future has been balanced by Grainger’s attention to the day-to-day operations of a business.

Together, they’ve built a company which employs around 60 people headquartered in the heart of Los Angeles. OTOY’s revenue doubled each year for the last several, according to Grainger. After all this time, Urbach still retains a “significantly” greater than 50 percent share in the company. This majority position even after a decade hints at the level of long-term trust investors have placed in their pairing. They’ve made connections throughout Hollywood and Silicon Valley with advisors like Google’s Eric Schmidt and investors backing them like Ari Emanuel, the co-CEO of one of Hollywood’s most influential talent companies and the inspiration for blunt-talking super agent Ari on HBO’s Entourage.

Emanuel showed up late one night on Urbach’s doorstep. As Urbach described it, he brought Emanuel over to his computer and showed him “3D objects with live ads and web links injected on the surface moving through portals of other apps and pages.”

“What the fuck did I know,” Emanuel said. “It looked great. I’d never seen anything like that.”

Urbach, though, wasn’t ready at the time for an investment. He supported himself taking work-for-hire jobs, like using his self-coded tools to render the complex scenes in advertisements for movies like Michael Bay’s Transformers. Today, the most recent versions of those tools are used by artists to create breathtaking photorealistic sequences like the haunting opening of HBO’s Westworld.

Urbach garnered support from people like Emanuel despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that his ideas can sound like the ravings of someone who sees reality quite different from most people. When speaking to outsiders, Urbach is advised not to discuss certain subjects because it can seem so far-fetched.

The truth is, even with influential investors and cutting edge technology, very few people understand OTOY’s place in the market or Urbach’s vision. Nevertheless, Urbach’s sleepless nights building his rendering technology, and Grainger’s diligent focusing of the business, have placed the startup at the cusp of a shift in computing that can change everything.

“OTOY is juggling a lot of widely different tech,” Oculus chief technical officer John Carmack wrote in an email to me. “But if you squint at it right, there are a lot of pieces that fit together in a particular vision of the future.”

The Brink Of What?

To understand OTOY’s position it is helpful to grasp some long-term trends.

Recently, VR started to approach consumer quality and pricing levels after years of failed attempts. Smartphones selling in the hundreds of millions made low-cost movement sensors and high resolution displays usable in more affordable VR hardware. In 2014, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg saw enough potential to bet $3 billion on the hope that the technology could form the foundation of the next platform for personal computing.

To kickstart adoption, this technology needed a reason for people to use it. Facebook, Sony, Valve, Samsung and HTC all bet on games. The gamble was that people who love video games and spend much of their free time using flat screens to immerse themselves in virtual worlds would be the first to seek out this technology.

Parallel to this evolution, sandbox video games started to emerge offering large 3D worlds for players to shape and explore. With the arrival of Minecraft around a decade ago, gaming crossed a threshold enabling millions of kids and adults alike to build vast and dynamic worlds using simple tools. For professionals, in recent years world engines gained popularity. Unity empowers skilled creators using the toolset to produce virtual worlds that could work on any personal gadget. Its leading competitor, Unreal, rolled out “Blueprints” allowing people to build worlds without any formal knowledge of coding.

The mouse, keyboard and controller that defined computer interaction in the last few decades of the 20th century are left behind with the rise of VR. In its place, intuitive human behavior becomes the way people shape these virtual worlds. For example, you just reach out and grab a cup with your hands in VR instead of moving a mouse to rotate that same object on a computer screen. It is a transformation still underway but the long-term trend here is that the barriers to creation are lowering. You can increasingly make the virtual world you want and quickly invite others to share it with you. At the same time the fidelity — the photorealistic look of these worlds — is dramatically improving.

“Games want to be cinematic quality and film wants to be interactive. So we see a new category of content that is linear interactive storytelling,” said Sylvio Drouin, vice president at Unity Labs. “Jules wants to make beautiful content accessible to everybody.”

[gfycat data_id=”FlippantEnlightenedDartfrog”]

Starting A Company

Grainger’s work is largely responsible for moving Urbach from operating in his mother’s house to employing dozens of people, with his technology being used by creatives scattered around the world.

She initially met Emanuel, who introduced her and a business partner to Urbach. Like Emanuel before her, Urbach brought her over to the computer and showed her his rendering technologies. Specifically, she saw the “sub-surface scattering skin shader I had done around 2004,” Ubrach said.

“I was a portrait artist at the time and was shocked by how realistically Jules was rendering skin,” Grainger said. “I knew immediately that what he was doing was important and that I wanted [to] help him.”

She called him afterward to find out what he needed. He very quickly asked for a light stage — an expensive technology used to capture the intricate way light hits the human body. It is used most often to capture actors and make realistic digital body doubles for big budget films or video games.

Urbach wanted it for his toolkit.

“It costs a lot of money,” he warned. “Maybe $2 million.”

Grainger rallied investors and delivered. Soon after, they decided to formally co-found OTOY.

“Jules needs a frictionless environment in order to operate,” she explained.

“I mean friction environments are fine, but they will be less optimal,” he continued. “And it will add a decade for no good reason, so…”

“So I try to create that for him,” she adds. “That’s what I do.”

“And we saved a decade, which matters in a space where like a week changes the world, especially when we’re at the pace we are now,” he said.

Pursuing A Vision

[gfycat data_id=”BlandPoliticalJay”]

The name OTOY is derived from Urbach’s love of toys. It is partially meant to mean “online toy”, which is key to Urbach’s vision that the future let anyone create whatever world they want. On that path, OTOY has gone through a number of evolutions in its 10-year history. At one point it was focused on streaming entire games from the cloud like failed startup Onlive and Sony-acquired Gaikai (it is worth noting that while Onlive failed, the acquisition of Gaikai freed executives there to kickstart Oculus). Go back earlier and Urbach was trying to make those AOL chat windows more interactive. So it would appear the company made a number of pivots over the years into new areas, but as Urbach and Grainger see it these were stepping stones on a path of developing streaming and rendering techniques built for the needs of the future.

“We were commercially focused on streaming entire games but always had the other technology in R&D,” Grainger said. “Since before I met Jules, he was developing rendering technology in the background and actually had rendering technology before streaming – this is what was used to do the renderings for his projects such as Transformers and what compelled me to work with him. The AOL connection in 2004 was from Jules’ understanding that all of this had to be connected through a social graph and at the time (FB didn’t exist yet) AOL IM was the biggest platform for this, so he hacked the AIM TOC protocol and used that to connect IM buddy lists into the shared rendered worlds he launched into a web page viewport from an AIM chat message. Jules showed this to me during our first meeting in March 2007.”

Today, the term “light fields” is what investors are chasing with their dollars. The promise of this technology helped Magic Leap raise roughly $1.4 billion. Even though current VR headsets can convince you that you’re in another world, they still lack certain characteristics of how we see in the real world. The idea with a light field is that it is visually indistinguishable.

Oculus chief technology officer John Carmack wrote in an email that he first met Urbach years ago “in the early days of Gear VR development, back when the early prototypes were still Galaxy S5 phones.”

“[Urbach] was already talking excitedly about light fields,” Carmack wrote. “Light fields may seem preposterously large today, but media types go through phases of adoption that end in sampling as the dominant distribution method: We used to have MIDI music with notes, but now we just have 44/48khz samples and mp3 compression. We used to construct images out of vectors and shapes, but now we have many megapixel images and jpeg compression. We used to do Flash style animations and panning for motion, but now we have 4k video and h264 compression. Today, we have rasterization and various depth augmentation hacks for 3D worlds, but in the future, we will probably have some kind of light field structure and dedicated compression technology.”

These are precisely the kinds of things Urbach put in OTOY’s tools over the years.

But as Urbach himself said, the pace of technology’s evolution is seemingly accelerating. Though artists like the creator of the Westworld opening discovered the usefulness of OTOY’s tech, whether it is necessary to the future or unable to be reproduced elsewhere is still an open question.

“The big challenge for them is balancing long term vision with a short term business,” said Brian Mathews, a vice president at software giant Autodesk who led an investment in OTOY. “Remember, when they started all this none of that [cloud, VR/AR] was there. They just knew it was going to be there.”

As a tech company in a fast-moving industry, timing is everything and they may need to see either rapid adoption or continued investment to level up. A pair of recent partnerships do give an indication of OTOY’s efforts to become necessary to large groups of people.

A recent partnership between OTOY and Facebook takes a volumetric slice of the world captured by new camera technology developed at the social media giant and puts it into a game engine where it can be manipulated. In VR, you could move around inside the footage in all directions or throw virtual lighting into the space to change the time of day. Or feel like a god and shrink this tiny world-slice down so it fits in the palm of your hand.

Another recent partnership with Unity represents a major play by the company, exposing its rendering tools to potentially millions of developers who could build gorgeous scenes with it.

“There are two schools of thought on how future VR/AR view-independent scenes will be represented for movie-like experiences,” wrote Tim Sweeney, CEO of Unreal creator Epic Games, in an email to me. “One is that it will be rendered in realtime by engines as VR/AR games work today (advantage: complete dynamism and interactivity), and the other is that it will be filmed with light field cameras and composited with offline rendering and then be stored in linear media fields as a light field movie (advantages: precise human and scene capture directly without the need for digitizing them as 3D geometry). Probably both [will] play a role.”

The intersection of these futures is exactly where Urbach and Grainger situated OTOY.

Emanuel doesn’t mince words in explaining his backing of Urbach and OTOY all these years. Urbach has helped guide him as technology changed the entertainment industry over the last decade, and Emanuel believes Urbach’s ideas will come to pass very quickly.

“I believe in somebody’s vision, and I believe they’re unique in what they do and I was willing to make a bet,” he said. “I’ve bet on worse.”

Creating The Holodeck

Urbach lugs a beast of a computer around with him most places. It is technically a laptop but using that term for this giant would be wrong. This machine belongs on a tabletop. Contained within are two of the most powerful consumer-oriented graphics processors made by NVIDIA. Just one of these GTX 1080 cards, with billions of transistors inside, is more than enough to literally draw a virtual world so realistic that when you put on a VR headset you feel like you’re there and can walk around inside of it. And Urbach has two of them in this machine. Any extreme rendering task he throws at it, the “laptop” can handle. This machine is kind of like a portable Holodeck.

While many VR-focused startups and entrepreneurs use Star Trek’s Holodeck as a general reference point for explaining their technology, with Urbach the desire to actually realize something like it is more personal. Part of it might be that one of his closest friends since childhood is Rod Roddenberry, the son of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry.

“He often tells me what he’s trying to do is create the Holodeck,” Roddenberry said. “Jules is an anomaly for sure. I know some really hard workers…Jules takes it to the next level. It’s derogatory to use the word obsessive, some people interpret it that way, but he is obsessive about what he does. It’s the passion. It’s the love. Every time I talk to him he’ll start very calm. And when that light bulb goes off in my head when I start to sort of understand what he’s talking about…the speed at which he speaks goes up faster and faster…He gets so excited. He truly loves what he does, even if it kills him. The older we both get, I get more and more worried…cause every time he seems to bring on more people and give them some of his workload he kind of finds a new angle to jump on and dives into it head-first and fully commits.”

The Holodeck as depicted in Star Trek is an off-shoot of the show’s transporter technology and it is certainly a work of complete fiction. But, if something like a Holodeck were ever truly realized, light fields might be the way at least part of it works.

“If you were to really build a Holodeck wall, it would emit a light field (not single color pixels) to give the general effect of a white light holographic image,” Urbach said. “You also need a light field display surface for a Holodeck so that objects in the real world are lit and reflect light correctly from the virtual on the other side of the ‘looking glass’. Basically light field displays at that size, would be like looking out a window, but with no hint of glass.”

For those unfamiliar, the Holodeck appeared in Star Trek: The Next Generation. A quarter century had passed between The Original Series and TNG, and in the show’s fiction nearly a century passed between the Enterprises of James T. Kirk and Jean-Luc Picard. The Holodeck represented the greatest technological leap forward in this aspirational future. It is a room where anything can be made, whether it be a recreation of events based on eyewitness accounts, a training program to better oneself or simply the occasional escape into fantasy.

“Star Trek hints at how human ingenuity might one day free us from the fundamental limits of the material universe,” Urbach said. “Warp drive and transporters, replicators and tri-corders – these commoditized space, time, health and money. But The Holodeck was the most revelatory one of all for me. I think it represents humanity’s earned transcendence beyond the ultimate final frontier- reality itself.”

Ian Hamilton is Senior Editor at UploadVR. He’s been writing about VR for five years. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.