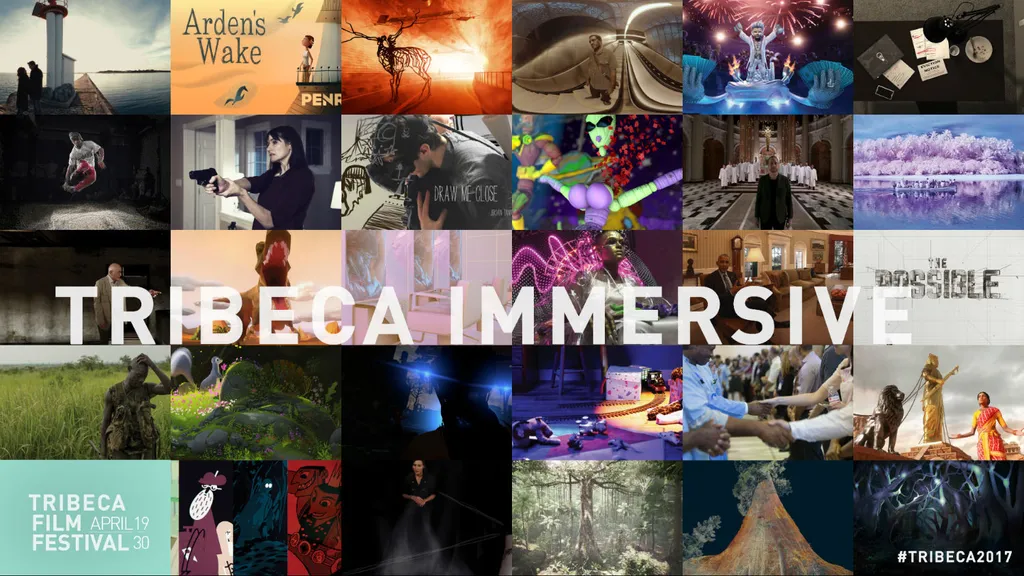

The VR Arcade at the Tribeca Film Festival presented another diverse set of experiences this year. With the release of Oculus Touch and Vive Trackers, the number of VR experiences that utilized motion controls went up since the last festival. But even more impressive, were the projects that used physical objects layered with virtual reality to bring greater immersion.

The most noteworthy of these was Draw Me Close, which I have already extensively covered. This meditation on childhood featured not only Vive Trackers on the back of your hands, but objects you manipulate such as a door and a window.

As Jordan Tannahill, the playwright behind Draw, told Upload VR, “It was important to me to craft an experience that was tactile, that invited full awareness of one’s own body and the body of another. I wanted to invoke the idea that this childhood memory has come to life so vividly it can be touched and interacted with.”

Trees

One project at Tribeca was simply called Tree, created by Milica Zec and Winslow Porter. You extend your arms out, holding Oculus Touch controllers. You experience the entire lifetime of a tree’s growth, from a tiny seed sprouting out of the ground, to a towering behemoth looking over the land. A vest vibrated at different stages of your growth, and scents of soil, plants, and later smoke, accompanied the piece. There was even fans blowing air when you grew tall.

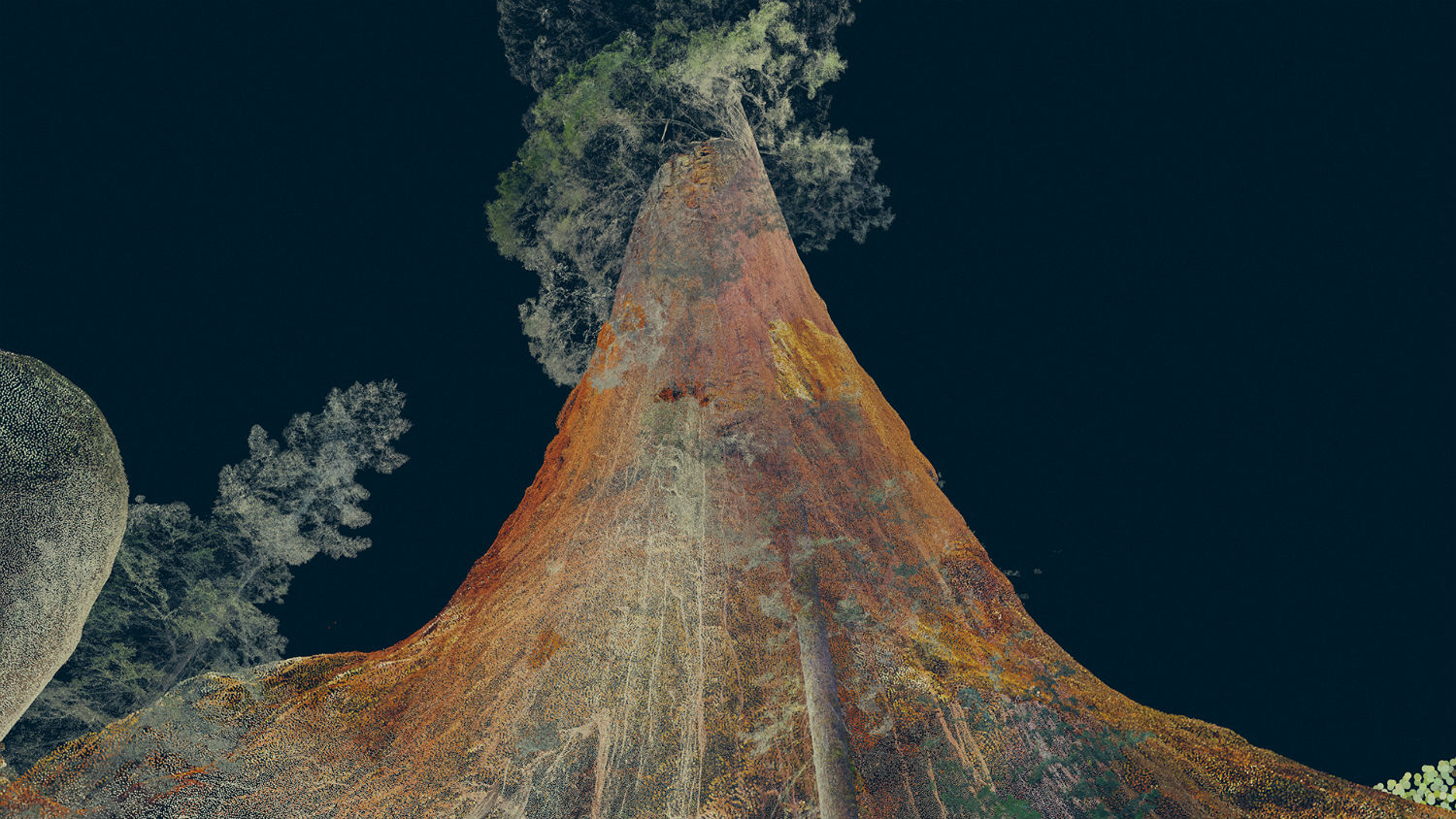

But another project really brought trees to life. It used Vive Trackers on the back of your hands and was called Treehugger: Wamona, from Marshmallow Laser Feast, a studio based in London. This project had a unique installation, a large foam tree with sections cut out of it where you can insert your hands. Around this tree were four stations, so more than one person can experience the project at a time.

“We love mixed reality. As artists, we have a mission to create experiences that change the way we see habitats and their inhabitants. Sense of touch & the tactile elements in our work are crucial to establishing and maintaining immersion. Discovering when you reach out and feel — or smell — something helps blur the line between the virtual and the real,” said Nell Whitley, the executive producer of Treehugger.

There was air flowing out of these holes, with the scent of pine coming from them. A haptic vest is also worn, providing a bit of vibration. In the experience, you are standing before this huge tree. The section with the hole has these tiny little colored spheres on the surface. Your hands can touch this surface, shoving and pushing them around. In real life, your hands, inside the fingerless gloves adorned with the Trackers on the back, would touch the soft foam there. You can move the pliable material, and see a similar manipulation in VR.

There are glowing strands inside the three, almost like veins of life flowing upward. After a few minutes on the ground level, you begin to slowly ascend up the side of this huge tree. It is as this point you can access the life flows directly, creating swirls and eddies of light, the general movement of your hands being tracked in the world.

Whitley said, “Treehugger, and its predecessor In the Eyes of the Animal are part of our research on microcosms and the human perception of nature. Historically advances in technology have taken us further away from nature, now, paradoxically technology has reached a point where it can start to revert the gap between ourselves and the natural world.”

It is a strange contrast that the latest technological medium is what Feast is using to help people reconnect with nature. And they wanted to use just the right tech to make it happen.

Whitley said, “Initially we were using Vive controllers to track the hands of the user, but as soon as we got hold of the Trackers we swapped them out. For the experience, it is really important to feel the structure with your fingertips — as well as being able to move freely while being tracked. Our next challenge in the pipeline is adding bio-sensors so we can get a feedback loop from the user to sync to our tree’s flow.”

Overall, Treehugger used the ability to touch and track your hands to allow you to interact with the subject of the experience. Though my headset lost tracking a few times, which the rep blamed on interference in the busy hall, I left that foam tree feeling like I experienced something unique.

Beds

Draw Me Close used a bed near the end of the narrative, but for the experience called Unrest, by Novelab from France, the bed was the entire point.

The bed is set in a booth that is made of up like a tiny bedroom. There is a shelf with books, picture frames of a bride and groom, and a large clock on the wall to the left. I climb onto the soft bed and the attendant helps me put on my Oculus Rift, then hands me a pair of Touch controllers.

The experience begins with a statistic: 17 million people worldwide have Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, also known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 25% of those afflicted are bedridden.

Then I am in studio apartment, laying on the bed. That same clock is on the wall to my left, as is that same wedding photo on the night stand. There is also other furniture, the large windows at the far wall, and other boxes of pills. It is all rendered in simple, but adequate graphics. And just like the real life subject, Jennifer Brea, you are stuck in the bed for the entire experience.

“Most of Unrest VR takes place with the user seated in bed, in a computer-generated reconstruction of the room where I was bedridden for years. VR works well as an installation because it gives users the opportunity to preview what they are about to experience. For us, the bed and other elements of the bedroom were about bringing the user into the story before they even put on the headset. However, what we discovered is that by seating the user on a real bed, something interesting happened — it became impossible to separate the virtual bed from the physical bed,” said Brea, who also co-directed the VR experience.

Using the touch, you can point at objects and Brea talks about her life. That photo brings about some thoughts on her wedding day, before she was afflicted with ME. Pointing at the clock brings her to discuss how each day goes on and on, each like the others before, a life in bed.

With Unrest, Novelabs used the physical object of the bed in two meaningful ways. First, like other experiences that put you in a chair and then you are in a chair inside the virtual world, having you in bed gets you in a tactile situation that mirrors the virtual situation.

Secondly, and more importantly, it helps you empathize with Brea and her disease. You are stuck in the bed, though most VR let you walk, or at least spin, around. You gain a sympathy for what a daily life confined to a bed must be like.

After ten or so of these mini monologues, the screen goes black. We soon see beautifully rendered neurons of light firing away. You gesture with the Touch controllers to get other neurons firing as they appear, with Brea talking about how well she knows the different parts of her brain now. And how they can betray her, losing their function when she unexpectedly “crashes.” As VR is an isolating, mental experience most of the time. This discussion of the brain while floating in darkness seems poignant. And we learn to feel what she is feeling mentally, beyond the physical sensations of the bed.

Brea said, “The nature of an invisible illness or disability is that from the outside, the body looks intact, whole. And so those who are outside of patient’s bodies, outside of their experience, cannot imagine the riot of pain or emotion or disturbance of sensory perception happening on the inside. Virtual reality is a medium uniquely positioned to help the public cross that barrier, where empathy and witness are not enough — when to truly convey the story, you need to bring the spectator directly into the experience.”

Novelabs plans to expand the 8-minute experience into 20 minutes. This will give everyone more time stuck in bed, living the life of Jennifer. The documentary film Unrest, that inspired the VR experience, is currently making the rounds at film festivals and will air on PBS in 2018.

Trains

Smack dab in the middle of the hall that had the VR arcade was the project Blackout, from Scatter. It was hard to miss because it was a section of a New York City subway car 20 or so feet long. It had plastic benches on each side like the subway, as well as the vertical poles of metal that were just like what commuters use everyday.

The car was long enough that two people could be in the experience at once, and once you had your Vive headset on, you were in a digital reproduction of an NYC subway sitting in a station. The computerized man known by all New Yorkers said his usual, “Stay clear of the closing doors.” And with that the train was moving.

Alexander Porter, the Director of Blackout, told Upload, “A lot of compelling VR projects take you very far away, special places you’d probably never go: foreign countries or other planets. It’s all very exciting, but for us, we intend to make a powerful filmmaking technology that people can use to tell human stories. For us, it’s more challenging to be close to home. In terms of our daily lives, the subway is radically close to home.”

James George, the Technical Director, added, “When we were doing user-testing in our empty studio, people would inherently go grab the [virtual] poles and be dissatisfied. One of the biggest things with room-scale VR is people’s confidence to move through the space. People are using the [real] poles and are totally exploring the space. They feel safe.”

I found myself holding one of the poles without a thought, comfortably falling into a position I had just been in earlier that day on my way to Tribeca. I saw the metal pole in VR and I grabbed it in real life. It was so natural, and so simple a gesture, but it put me right in that car mentally.

During that 10-minute ride, you can look at the other passengers riding the train, hear their inner-thoughts and stories of their lives. Sometimes it is about their lives as a racial minority, such as a Latina woman worried about her family being deported. Sometimes it is about their religion, such as the Muslim woman with her hair covered, knowing that it labels her for the whole bigoted world to see. Sometimes it is about their political views, as one man thinks about President Trump bombing Syria.

You did read that correctly — Scatter has interviewed and filmed people earlier that week, and was actually doing more during the second half of Tribeca, adding more subjects to the train car, to provide an even wider breadth of humanity. I eventually sit down on one of the benches to listen in to a few of them. To learn other perspectives, as I ride the train like I always do.

Porter said, “The question is: what’s different about a premiere? About a showing in a context like this, that you can’t see in your living room? The point in making an installation is not to make a little diorama. When a person is in VR, they aren’t seeing [the installation]. When we are designing this thing, we might as well make it look totally different, but, on a tactile level, feel the same.”

So for Scatter, building the sizable train not only enhanced the experience, it was a matter of presenting something special at the festival that you wouldn’t be able to get anywhere else.

The Blackout project had another purpose as well, to show off DepthKit, a video solution that combines depth data from cameras like Microsoft’s Kinect with normal video, to create volumetric figures on a budget. For Blackout, they use five such Kinect cameras arranged around a person, to capture them in three-dimensional space. The result looks almost like liquid photographs, not realistic, but it gives you the sensation of seeing the form of a person.

George said, “The technology is designed to be legible to the filmmaking community. Our use of standard video equipment and video workflow is to make it exciting to people who are used to video production, then dip their toe into six degrees of freedom or volumetric filmmaking.”

Scatter has another VR projecting being released soon, named Zero Days, that utilizes DepthKit. And as with Blackout, it gives the people present a visceral presence, but in an artistic style.

Getting Physical

So these different studios were providing different experiences with a different array of physical interactions, each with unique purposes. Some to immerse more, some to instill empathy, and some to be unique and different. Each were effective in their own ways, depending on their purpose.

I was in a bed. I was sitting in the New York City subway. I did manipulate the world with my own hands. All of this physical interaction makes VR’s strengths as a unique medium even more effective. And with VR at home unlikely to gain good haptics or tactile tools any time soon, it is these premium experiences at festivals and events that could ultimately be the prime place for that evolution of immersion.