This week saw the first ever conference dedicated to virtual reality (VR) technology in the south of the UK. Organized by Bristol-based indie game developer Opposable Games the conference saw VR developers from across the UK descend upon the amazing At-Bristol Science Centre to share their knowledge of technology’s newest and most burgeoning arrival; and to show off a few cool experiences too.

Hosted by games journalist Will Freeman, the conference kicked off with Sony’s Dave Ranyard quite appropriately discussing how VR is a new world for creative developers. With what would become a recurring point throughout the day, Ranyard established VR as being about presence, true immersion and, most importantly, ‘getting an experience you might never get’ anywhere else. To illustrate this point he showed a charming video of Sony’s VR experience The Deep played by his mother – her reaction to encountering a great white shark being truly priceless.

This idea of VR as being a totally new experience for people – to both those familiar with the technology and those completely new to it – was further developed by Henrique Olifiers of Bossa Studios. Olifiers stressed the importance of the first moments in which someone encounters VR as being a make or break moment for the technology. From Bossa’s own work with VR Olifiers advised against using ‘shock and awe’ during the initial moments of the experience as the user is already in a state of sensory overload. Olifiers also noted that one of the major issues VR faces is control; in time, he hopes, a standard control interface will emerge for VR.

Complimentary technologies were discussed by the next two speakers: Patrick O’Luanaigh of nDreams and Tom Carter of Ultrahaptics. O’Luanaigh highlighted the potential for Augmented Reality (AR) to enhance VR by drawing the user into a VR experience through a more natural and gentle access point. O’Luanaigh suggested that a combination of AR and VR could make the potentially isolating VR experience more sociable and prove beneficial for both technologies.

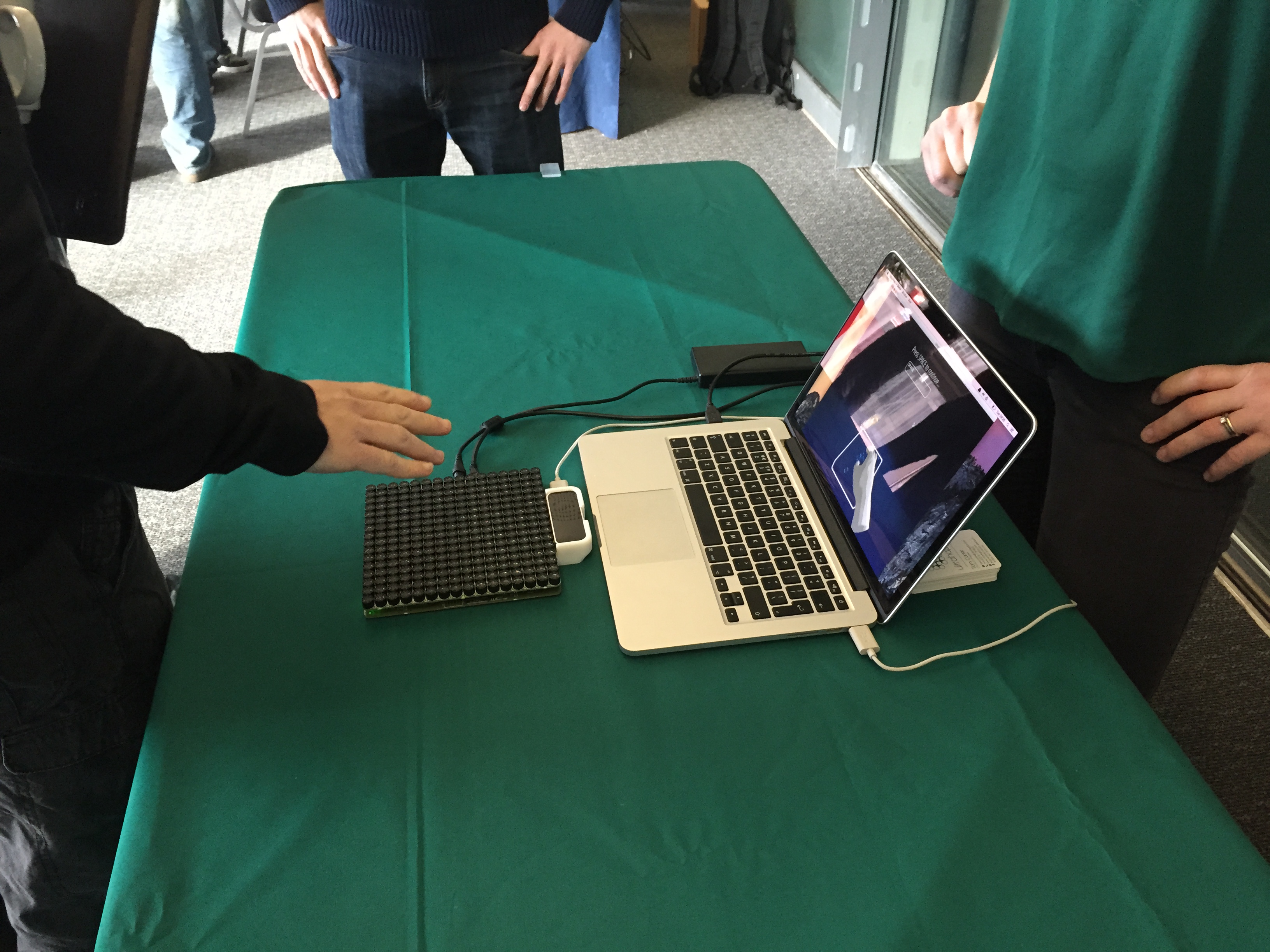

Tom Carter and Ultrahaptics certainly turned the most heads at SouthWest VR with their physical feedback ultrasound technology. Carter theorised that whilst VR enhances the user’s audio and visual senses it neglects the user’s sense of touch – and thus not reaching its potential as a truly immersive experience. By using Ultrahaptic’s unique ultrasound air pads, the user is able to physically feel 3D shapes in the air around them. Such examples on display included the sensation of bubbles popping against your skin and passing your hand through a force field. Needless to say, the Ultrahaptics stall was one of the busiest with people queuing out of the door to have a go.

As a game developer it’s sometimes easy to forget that VR has a huge amount of application outside of gaming. The number of filmmakers present, however, certainly solidified this point.

Phil Harper of AlchemyVR kicked off the discussions for VR’s potential as a filmmaking tool by suggesting the act of watching in VR can be stronger than interacting. Advocating the power of 360 degree video in VR filmmaking, Harper suggested the technology has the power to allow the audience to ‘forget themselves and be brought into the world’ of the film. Whilst AlchemyVR currently developer VR documentaries, their aim for the future is to use the technology to create fictional dramas but hinted that one issue creators will have to consider is whether emotions in VR are enhanced too much – citing some of the truly terrifying VR horror films currently available.

Stephen Gray highlighted VR filmmaking’s limitless potential as an educational tool. Using his own Moved by Conflict exhibition at Bristol’s MShed museum as an example, and echoing Phil Harper’s opinion that watching is as strong as interacting, Gray pointed out that the passive nature of the VR experience enhanced the immersion felt by guests to the museum. A touching response from one historian to Gray’s exhibition highlighted the captivating power of VR as they revelled in the chance to travel back in time through Bristol’s past.

Edward Miller of Immersiv.ly discussed VR filmmaking’s potential as a broadcast tool. Miller suggests that VR is currently in the age of spectacle similarly experiences by early filmmakers such as the Lumiere Brothers; where experimental ‘play’ is currently more important than narrative clarity. In time, Miller suggests, VR filmmaking can develop into a new medium for telling truly evocative and in-depth stories though mentioned that filmmakers will have to learn a new rulebook to create good experiences. Miller highlighted the recent use of 360-degree cameras to film pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong as an example of the emotive potential of VR broadcasting, as the audience became more immersed in the event unfolding onscreen.

Andre Lorenceau of Innerspace seemed to contradict Edward Miller by suggesting that VR filmmaking’s greatest strength laid in its ability to unleash creativity rather than capture real life. Innerspace’s visually stunning body of work features VR experiences in truly fantastical environments. Whilst Duncan Burbidge of Third Floor Inc. continued the argument for fantasy trumping real life and spoke of how VR’s world building capabilities have benefited traditional Hollywood filmmaking. Burbidge continued by asking questions of VR filmmaking such as how can filmmakers maintain the audience’s focus and whether, in time, all VR platforms will work on a common format.

Returning to VR gaming, Katie Goode of Triangular Pixels imparted game design advice learnt from the development of Smash Hit Plunder. Goode highlighted the importance of finding inspiration outside of games when developing for VR and stressed the importance of ‘tactile immersion’ in the VR space. Using elements such as shadows and world interactions are key to enhancing tactile immersion for gamers.

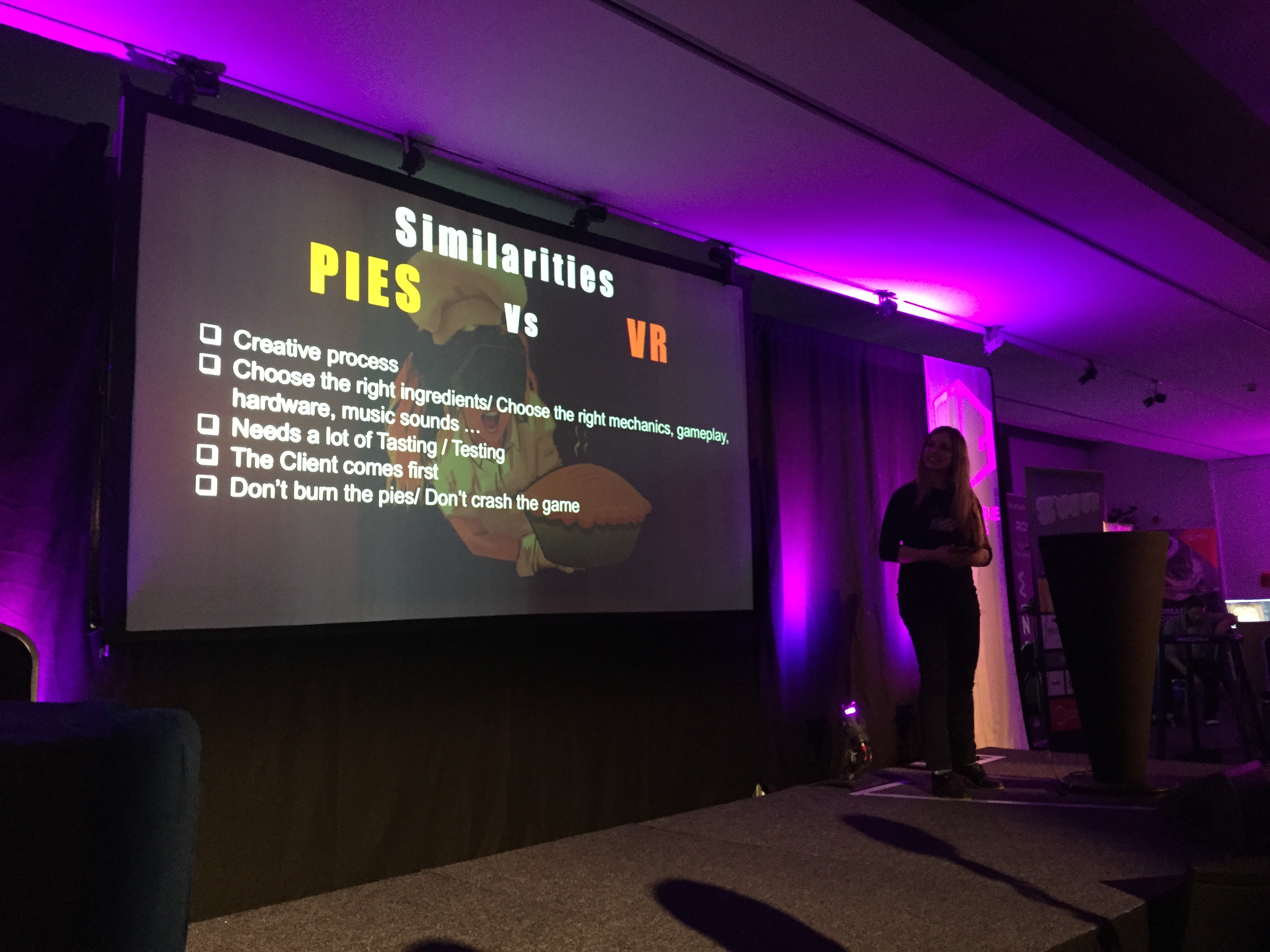

Pixel Rift developer Ana Ribeiro gave an inspiring talk of her journey from pie shop owner in Brazil to VR game developer in the UK. Using pies as a charming allegory, Ribeiro stressed the importance of testing, learning and creating a community as the key to VR success. Ribeiro’s story teaches us that lessons from all aspects of life can teach us to make games whilst highlighting that, as a new technology, VR has opened the doors for new developers.

Filmmaker Nick Pittom of Fire Panda explored the exciting potential of VR as a technology for real-time storytelling that can adapt to the audience’s control. Traditional storytelling, according to Pittom, is limited when compared to the opportunities made possible by VR. Much like Katie Goode, Pittom suggested looking to other storytelling mediums such as theatre and games for inspiration when creating a VR story but stressed that traditional filmmaking rules do not work in VR and that a new language would have to emerge. Pittom suggested that technology such as Gaze Cues would be integral for allowing the audience to control the narrative of their VR experience.

Games as a medium have started to become insular with regards to subject matter, suggested Mark Washbrook and Paul Colls of Fierce Kaiju, but VR has the potential to tackle bolder and braver subjects. Commenting on how many of todays game developers were inspired into games by games of the past, Washbrook and Colls suggested that by embracing new subjects, that people care about, it’ll inspire the next generation of developers.

The day was rounded off by a panel discussion featuring Dave Ranyard of Sony, Henrique Olifiers of Bossa Studios and Kevin Williams of The Stinger Report. The panel identified that the strengths of VR are found in the immersion of its ability to allow the user to interact with characters and the environment. As a storytelling medium the panel stressed the importance of making the user a part of the story and using the environment to tell a story. Kevin William’s highlighted that the reaction from traditional filmmakers towards VR as a sign of the medium’s storytelling potential, but stressed that making VR content readily available should be one of the industry’s key objectives. In time, the panel agreed, VR technology would need to create an industry standard for the potential health effects of using VR, and that developers should be prepared to encounter barriers.

VR is still a ‘stage one’ technology just beginning to bloom. The doors have been flung wide open and creativity is pouring in though, as many of the conference talks noted, creators and developers are still at the ‘play’ stage; eagerly learning how to create compelling experiences and stories. With each step being taken forward the industry is discovering new ways to create but also asking important questions that must be answered about health, artistic language and accessibility. Events such as SouthWest VR bring people together and, as Will Freeman surmises, ‘knowledge sharing benefits VR’. This year’s event felt tailored to exploring the potential of VR technology. In the twelve months between now and the next SouthWest VR event it’ll be fascinating to see how VR grows as a technology and an industry. With a number of different disciplines experimenting with VR it truly is an exciting time to be at the dawn of a new technological medium.

—

Daniel (@D_Dowsing) is a games writer and designer at indie games developer and VR specialists Opposable Games. For more information on their services check out www.opposablegames.com